In the second of a new series of blogposts celebrating the forthcoming exhibition, Nurture Through Nature with Children’s Books, opening at the Museum of Edinburgh on 1 May 2025, Sara Yahya Hamed opens a door onto the world of magical and fantastical creatures found in the enchanted realms of the Arabian Nights.

*

Ever since A Thousand and One Nights was translated by the French Orientalist Antoine Galland, these tales found their way into Europe, as well as British and Scottish libraries and households. Published between 1704–1717 as volumes of the Arabian Nights Entertainment or Les Mille et Une Nuits, these tales found their way from the Arabic manuscript to French, and eventually to English. The translations of these tales made them accessible to personal and public libraries; over time, these medieval tales grew to become a children’s favourite, and for good reason.

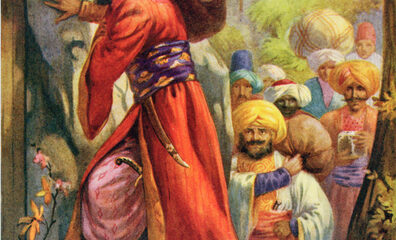

The Arabian Nights Entertainment did become a source of accessible entertainment for the children of eighteenth and nineteenth-century Britain. The folkloric tales were republished later in different translations and formats: whole volumes, chapbooks, stories, plays. Such formats were more accessible to children due to their compactness and readability. An example of these chapbooks includes ‘The History and Wonderful Voyages of Sindbad the Sailor’ and ‘Ali Baba, or the Forty Thieves’ within the collection of Juvenile Books, published in Edinburgh by James Clarke & Co in 1825, and currently held at the National Library of Scotland. The title ‘juvenile’ addresses a specific audience, and suggests the friendliness and familiarity children could experience while reading these tales.

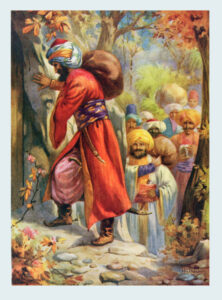

The Arabian Nights introduce children to the fantastic world of animals. ‘The Second Voyage of Sindbad the Sailor’ is among tales that take children on adventurous journeys and narrate details about extraordinary serpents: ‘that was a great number of serpents, so big, and so long, that the least of them was capable of swallowing an elephant’ (148). In addition, ‘The History of the Third Calendar, a King’s Son’ highlights a mythical bird that can carry elephants: ‘this roc is a white bird of a monstrous size, his strength is such that he can lift up elephants from the plains, and carry them to the tops of mountains, where he feeds upon them’ (117). The figure below shows Sinbad’s size in comparison with the roc’s giant egg. Imagining animals of extraordinary size creates a sense of wonder for children and diverts their imagination towards fantastic realms.

Figure (2): Frederick Warne. Sindbad Fastens himself to the Roc’s Leg, 1880.

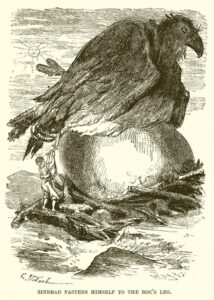

The Arabian Nights also display fantastic creatures that are hybrids of humans and animals. While European narratives narrate tales about hybrid centaurs, the Arabian Nights showcase something much more exotic: a waterman ‘whose head was like an elephant’s, and his body like a tyger’s’ in ‘The History of Prince Zeyn Alasnam, and the King of the Genii’ (577). Sources also indicate that myths about merfolk originate from the Arabian Nights before Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Little Mermaid’ was published in 1837. Helen J. Callow states that:

[…] tales of mermen exist in British as well as Middle Eastern tale traditions, from the Scottish Blue Men of the Minch to the merfolk of the Arabian Nights. Edward W. Lane produced one of the most important English translations of The Arabian Nights (1839– 41), which includes a tale in which Abdallah of the Land catches Abdallah of the Sea— a merman— in his fisherman’s net. The two men bond, and Abdallah of the Land takes a voyage to the kingdoms of the sea. (1301)

Merging human figures with animals creates a space for a fertile juvenile imagination. Reading about the extraordinary can take children from a sense of reading for education to reading for entertainment, which teaches them much about imagination and other cultures alike.

Figure (3): Folkard, Charles. Illustration to the Arabian Nights. Towner Art Gallery, [undated but estimated c.1917].

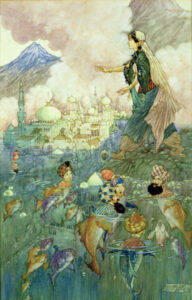

Lastly, the Arabian Nights displays animals to convey magic. ‘The Story of the Enchanted Horse’ showcases an artificial horse that not only appears to be real, but also owns magical abilities and can transport anybody to any and every place. This horse gets offered to a king in the tales; the story narrates: ‘an Indian appeared at the foot of the throne, with an artificial horse, richly bridled and saddled, and so well made, that at first sight he looked like a live horse’ (796). The character states:

Whenever I mount him, be it where it will, I can transport myself through the air, to the most distant part of the world, in a very short time. This, sir, is the wonder of my horse; a wonder which nobody ever heard speak of, and which I offer to shew your Majesty, if you command me. (797)

Children in modern times often watch shows about characters with superpowers; meanwhile, children of eighteenth and nineteenth-century Britain were exposed to the supernatural through tales like the Arabian Nights. The Enchanted Horse is therefore not merely a fictional addition to the narrative; it can expand children’s critical thinking as it touches on questions of magic, realism, and artificiality. Creative imagination is a highly valuable element of childhood; yet the Arabian Nights offers an imagination that can transform into critical thinking and transport itself to adulthood.

Figure (4): Folkard, Charles. The Story of the Enchanted Horse, 1917.

While Galland refers to the tales as Arabian Nights Entertainment, I believe they bear much more than an entertainment for young readers. The tales bear the soul of medieval Oriental culture that touches audiences from all ages. They are the kind of stories that you read as a child, yet they never leave you. There’s a special place in the minds of the Arabian Nights’ readers that bear the memory of these tales and the lessons learnt from them: a memorial space of childhood essence that no other narrative can ever fill.

Sources

‘Ali Baba, or the Forty Thieves’, Juvenile Books. James Clarke & Co, 1825.

Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Edited by Robert L. Mack. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Helen J. Callow (ed.), Folktales and Fairy Tales: Traditions and Texts from Around the World, Bloomsbury, 2016.

‘The History and Wonderful Voyages of Sindbad the Sailor’, Juvenile Books. James Clarke & Co, 1825.

Recommended reading

Kennedy, Philip F. and Marina Warner. Scheherazade’s Children: Global Encounters with the Arabian Nights, New York University Press, 2013.

Lathey, Gillian. The Role of Translators in Children’s Literature: Invisible Storytellers. Routledge, 2010.

Stephens, John, and Robyn McCallum. Retelling Stories, Framing Culture: Traditional Story and Metanarratives in Children’s Literature, Taylor & Francis Group, 2006.

Styles, Morag. ‘Learning through Literature: The Case of The Arabian Nights.’ Oxford Review of Education, vol. 36, no. 2, 2010, pp. 157–69.

*

Sara Yahya Hamed is a PhD Candidate in English Literature at the University of Edinburgh, where she also did her MSc in Literature and Society: Enlightenment Romantic & Victorian. Her PhD investigates Orientalism in Romantic poetry and intertextuality with the Arabian Nights. Sara is currently an Assistant Editor with FORUM (University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts) and the Seminar Secretary for LAMPS (Late Antique & Medieval Postgraduate Society). She’s also a creative writer and a self-published novelist: the author of Crimson Ruby, Immortal Breeze, and the 2021 AmiChoice Award winner, Noble Creatures.