What secrets can the skills of a cataloguer unlock about a book collection? In this blog, Kathryn Downing, MSc student in Book History and Material Culture at the University of Edinburgh, shares some fascinating insights from her experience working with some of the oldest books in the Museum of Childhood’s archive in the ongoing process of making its treasures more accessible.

*

One of the biggest barriers to conducting research can be an un-catalogued collection. It is not often – if ever – that libraries and museums let you peruse their stacks or stores to your heart’s desire. Researchers, then, often become experts at navigating catalogues and databases in an effort to locate the right resources. In many cases, the strength of someone’s research is dependent on the strength of the records they can access.

If you’ve been following SELCIE’s work at Edinburgh’s Museum of Childhood, then you’ve witnessed one of those rare times when a museum does let researchers into a store to peruse its contents. During the SELCIE team’s time collaborating with the museum, they have produced a publication and an exhibition in addition to pursuing individual research topics. More valuable than even these tangible outcomes, however, is the process they began of sorting and organising the thousands of books residing in the City Chambers. Simply knowing the extent of the collection is the first step towards facilitating public access to it.

Although SELCIE has made great strides in uncovering the treasures of the City Chambers book store, much still remains hidden. The sheer extent of the Museum of Childhood’s book collection (an estimated 15,000 items) has means that many important details associated with the books remain unrecorded. While publications and exhibitions are a fantastic way to bring collections to the community, knowing what to write or display next can be challenging when there are thousands of items and no way to search through them efficiently.

Enter the cataloguer!

This past Spring, I had the opportunity to work with some of the oldest books in the Museum of Childhood’s collection. As a postgraduate student pursuing work with rare books and print, I am a firm believer in increasing the accessibility of library and museum collections. I was, therefore, more than willing to help the Museum of Childhood build detailed records for books in their pre-1850 collection, in the hopes that some elements of the books that I discovered and recorded may help future researchers with their own projects.

While my own academic studies have taught me a lot about conducting research, my past experience working with library and museum catalogues has taught me even more about how to facilitate it. While the researcher needs a keen eye to spot relevant information for their own topics, the cataloguer needs to spot all details that could be relevant to any research subject. Moreover, those details need to be recorded in a way that ensures they can be easily retrieved from a catalogue or database by those who need them. The way an item goes into an institution’s catalogue can help or hinder research possibilities, as you’ll see with some of the examples I have from the Museum of Childhood’s own collection.

Naming the Unnamed

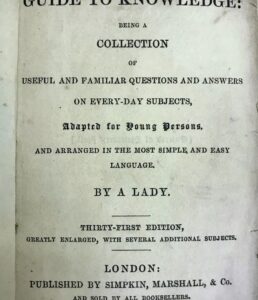

The very basics of all records for books include information about their authors. When working with older books (and especially children’s literature), however, determining the author can be much less straightforward than you would imagine. Take, for example, The Child’s Guide to Knowledge. This book was popular enough to go through sixty editions – the Museum of Childhood has the thirty-first – but its title page only says the book is by “A Lady.”

That the book is simply the work of “A Lady” is important information to include in its record – those looking to study 18th or 19th-century anonymous or pseudonymous publications must be able to identify this item as relevant to their research – but even more important for the record is that Lady’s actual name, Fanny Umphelby (1788-1852).

When the book was first published in 1825, authorship was mistakenly attributed to Fanny’s sister – an error corrected by Fanny’s nephew in the 1899 edition of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (1). Modern catalogue records need to reflect the way the book was initially presented – i.e., “by a lady” – as well as link to further information that gives Fanny Umphelby her due place in history.

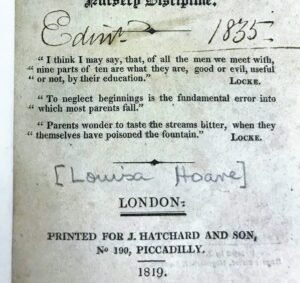

We can see explicit evidence of cataloguers giving names to unnamed authors in this first edition of Louisa Hoare’s Hints for the Improvement of Early Education and Nursery Discipline.

This book was an earlier addition to the Museum of Childhood’s collection, accessioned back when the museum was sharing space with Edinburgh’s public libraries. The penciled notation of Louisa Hoare’s name on the title page was most likely added by the cataloger in the accessioning process. While common practice is no longer to write directly on the rare books being cataloged, we appreciate the cataloguer’s efforts to give credit where credit is due!

Placing the Book in History

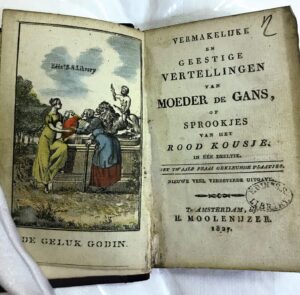

Often an interesting research inquiry is not only about a book’s contents, but also involves the life that book lived post-publication. A Dutch version of the tales of Mother Goose, Vermakelijke en Geestige Vertellingen van Moeder de Gans (“Amusing and Witty Stories of Mother Goose”), has a curious shelf mark that alerted me to what had to be an interesting provenance.

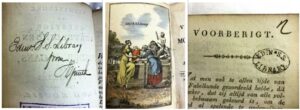

Although many items in the museum’s store have been marked in some way by previous accessioning, this shelf mark didn’t match any system that the Museum of Childhood has used to organize their collections. Upon opening the book, however, I found exactly from where that mark came: Edinburgh’s Select Subscription Library.

Scottish subscription libraries followed the pattern of Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Philadelphia (established 1731 in what was then the American colony of Pennsylvania), and became relatively common in lowland Scotland by the 1800s (2). The idea was that if members of a community wanted to borrow books, they “subscribed” to the library – paying a flat rate to join, then monthly or annual dues to retain borrowing privileges. The Edinburgh Select Subscription Library (1800-1880) was created as a rival to the Edinburgh Subscription Library (1794-1900) when ten men became frustrated with the high prices of the original subscription library and decide to set up their own in a printer’s shop on High Street.

As you can see, there is no small shortage of the library’s property stamp. “Edin. S.S. Library” makes an appearance on just about every page prior to the stories themselves.

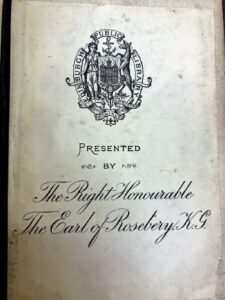

As far as we know, this book is the only one that made it from the Edinburgh Select Subscription Library and into the Museum of Childhood’s collections – but not before coming into the hands of the 5th Earl of Rosebery, Archibald Philip Primrose.

When the Museum of Childhood was storing items in space borrowed from Edinburgh’s public libraries, donated items included a book plate with the donor’s name. This book has a rather elaborate one, telling us it was presented to the museum by the Earl of Rosebery, K.G.

These markings – the shelf mark, library stamps, and donation plate – are important copy-specific additions to the book’s record in the museum’s catalogue. This item’s provenance would be highly relevant for research or exhibit topics concerning foreign language children’s literature, subscription libraries, the Earl of Rosebery’s collections, or any number of other investigations, but would be almost impossible to identify as such unless these details are catalogued and searchable.

Bringing the Information Together

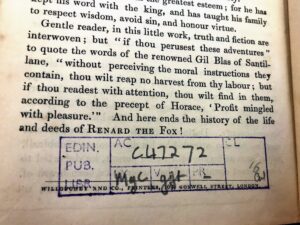

As I mentioned earlier, many items in the collection contain markings from the museum’s previous systems for accessioning items. The Museum of Childhood has been collecting books since it was first established in the 1950s, but changes in both technology and professional museum practices have affected the way it maintains records throughout the decades. As far as I could tell, books in the museum’s special collections have been accessioned in at least four different ways.

The original accessioning system was established by the museum’s founder, Patrick Murray. He wrote inventory numbers on the items in red (the museum refers to them as “red numbers”), and kept a corresponding inventory list with basic, handwritten information about the item.

No-one at the museum (or public libraries) today knows how to decipher these accession numbers, meaning information such as a donation or accession date that may have been encoded in an item’s number is now lost.

In 2004, The History of Renard the Fox was accessioned again and assigned a number similar (but not quite the same) to those used today, but with minimal details about the item added to its record. Luckily, the 2004 number is decipherable by current museum staff.

In addition to creating or updating records to reflect the kinds of information I have shared about The Child’s Guide to Knowledge and the “Amusing and Witty Stories of Mother Goose,” I did my best to cross-reference any additional markings on the books that may refer to corresponding written records. More than once, checking these records led to additional information about the item – such as a donor’s name or a donation date – that I could then add to the book’s electronic record.

As important as it is for a cataloguer to identify and record information about the book, it is also necessary to note how the museum has handled the book. Even though The History of Renard the Fox had multiple accession numbers by the time I added it to the museum’s electronic catalog, I detailed each one and noted where they had corresponding handwritten records. In the event that more information comes to light about those undecipherable public library stamp numbers, the curator can simply search the catalog for all items with such a stamp to update their records instead of having to sort through the entire collection of books.

As the examples in this post have shown, a thorough and searchable catalog for museum collections is essential to developing our further understanding of them. Even more so now than in the past, technology is providing us with a way to bring together previously scattered pieces of information. Having this information in one place gives us the ability to search through large collections efficiently, make comparisons between items, and track changes in museum practices – as long as we get the appropriate information into the catalog first!

References:

(1) Susan Drain, “Umphelby, Fanny (1788 – 1852), author,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, last modified September 23, 2004, https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-27994.

(2) K. A. Manley, “Scottish Circulating and Subscription Libraries as Community Libraries,” Library History 19, no. 3 (2003): 189, doi: 10.1179/lib.2003.19.3.185.

This post by Kathryn Downing

About Kathryn

Kathryn Downing studied literature at the College of William & Mary in Virginia before moving to Edinburgh to pursue a Master’s degree in Book History and Material Culture. She recently completed a dissertation on authorship and folklore, and continues to work with special collections in both libraries and museums.