There are many elements of the Museum of Childhood collections that reflect what was happening in the world at the time they were made – fashion can be followed in the costume collection, technology in toy manufacture and popular film stars in dolls and magazines.

The book collection, however, offers a unique insight into not just what adults were communicating with children about the world, but also what the child thought about what was happening and what they were being told. Through inscriptions, drawings and hand-made publications by children we have access to their perspective on the world around them. The Museum holds a series of magazines called The Pierot made by a group of children across Britain in 1910-1914.

The authors were spread across the UK, with given addresses for Essex, Edinburgh, near Bristol, Yorkshire, County Down, County Derry, Fife, Suffolk, Kent and Hampshire. The magazine was circulated by post, the cost of the stamp being the subscription fee, and each child would add their own contributions, remarks and advertisements, before passing it on to the next contributor. Those who held onto the magazine for more than 3 days were charged a fine of one pence for each additional day, which would be passed on to Dr Barnado Homes. There is an awareness of charitable acts represented throughout the magazines. It was common at this time to encourage children to raise money for charitable organisations and be aware of those less fortunate than themselves.

Seen throughout the editions of the magazine is the influence of the popularity of fiction and romantic stories, an interest in fashion with colour illustrations in watercolours, and poetry. The magazines are a creative output for the children, and they are also seeking validation from their peers on their efforts with pages for comments and votes for the best submissions at the back of the magazine – comparable to ‘likes’ on social media today.

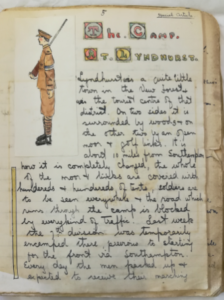

The Camp at Lyndhurst written by Miss R Dent of Beacon Corner, Burley, Hampshire, on the edge of the New Forrest near the village of Lyndhurst, is a perfect example of the other subjects in the magazine, that of the children having an awareness of world events and an interest in them. As well as this article, there are several other references to the ongoing conflict in this edition and an advertisement that offers the sale of wooden toys with funds raised going to the Belgian Relief Fund.

The war had started in July of 1914, and by the autumn when this issue was circulated, the true horrors of what was to come had not even been grasped by the adults, let alone filtered down to children’s consciousness.

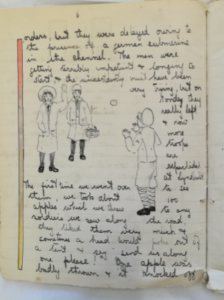

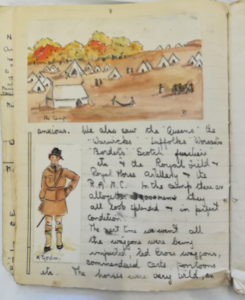

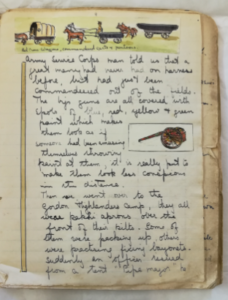

The Camp at Lyndhurst is written as a jolly tale of chatting to the soldiers and the men are making jokes about what will happen at the front – was this what the men naively believed war was to be like or were they making the best of it for the benefit of the children? The author describes the landscape: ‘The whole of the moor and links are covered with hundreds and hundreds of tents, soldiers are to be seen everywhere & the road which runs through the camp is blocked by every kind of traffic. Last week the 7th division was temporarily encamped there previous to starting for the front via Southampton – they were delayed owing to the presence of German submarines in the Channel.’ This shows a good level of knowledge about the activities at the camp and the shipment of troops, gleaned from newspapers or adult conversations.

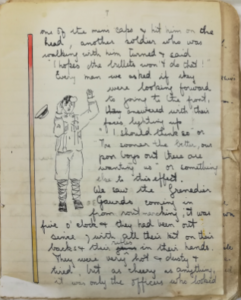

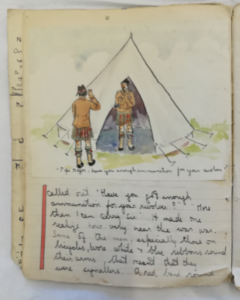

‘The first time we went over to see them we took about 100 appleswhich we threw to any soldiers we saw along the road. One apple was badly thrown & it knocked off one of the men’s caps and hit him on the head A passing soldier said I hope the bullets won’t do that! Everyman we asked if they were looking forward to going to the front answered with faces lighting up “I should think so” or “The sooner the better”’. The author goes on to describe what batallions were in the camp, that they were marching in full kit for hours, what they wore, how there were big guns covered up and they were practising fixing bayonets: ‘It made one realize how very near the war was.’

There is a fascinating postscript saying that since writing the article the Scottish troops had left for the front and have been replaced in the camp by Indian troops, reflecting the fact that soldiers from all over the British Empire were brought into the conflict. The author describes in detail what they are wearing, how they ride bareback, and that their shoes were heelless. It is possible they hadn’t been given their uniforms for the front yet and were still wearing clothes more suited to the warmer climate of India: ‘They nearly all have bare legs and heelless slippers and they look rather cold.’ They are described as wearing turbans and were probably part of the 130,000 Sikhs who saw active service in the conflict. Although accounting for just 2% of the population of British India at the time, the Sikhs made up more than 20% of the British Indian Army at the outbreak of hostilities.

On page 29 of the magazine, Elegy of a Dying War-Horse by C. Turton shows a more realistic idea of what war must be like – ‘All around us lie bodies of dead men and dying, Some passive, and others contorted with pain, And one Highland laddie – a mere boy of twenty, Is groaning, and moans for his “mither and hame”‘. The poem speaks of the hot sun in the Indian valley. The Charge of the Light Brigade by Tennyson and tales of Clive of India would have been familiar to children at this time and would inspire heroic ideas about British soldiers and battles in faraway lands.

This September to October 1914 edition of The Pierot is the last one in the Museum’s collection. It isn’t clear if this was the last one made or not, but certainly as the authors got older their interests would have moved on. The magazines offer a wonderful insight into the lives of the children who contributed – their interests, concerns and creative talents – as well as a window into the world around them.

This post was written by Lyn

Is it possible for visitors to see the collection of these magazines? I am at teacher and also currently studying for an MEd in Children’s Literature and would love to see these magazines for myself, though I also think some of my pupils would be keen also.

Hi there, Thanks for your interest! I think Lyn will be in touch with you about this!