Eighteen months on from our first descent into the Museum of Childhood’s basement vault and every box still tells a story. In one we opened lay two beautifully illustrated volumes from the early twentieth century. Several threads bound them together — pooled from the same body of legends and stories from the great literary cycles of Irish and Scottish tradition, they show how the development of children’s literature pierces at the heart of questions about culture and identity, tradition and ‘belonging’. And how the seedstore of myth and legend is an ever-present inspiration for creators of children’s stories…

*

‘It was Aibric who remembered the story of the children of Lir, because he loved them. He told the story to the people of Ireland, and they were so fond of the story and had such pity for Lir’s children that they made a law that no one was to hurt a wild swan, and when they saw a swan flying they would say: “My blessing with you, white swan, for the sake of Lir’s children!’ – from ‘The Children of Lir’

*

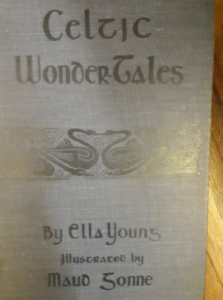

Celtic Wonder Tales (1910) was the work of Ella Young (1867-1956), an Irish nationalist, Republican sympathiser, and poet. Born into a Presbyterian, unionist family in the north of Ireland, she learnt Irish Gaelic and became a member of the Dublin Theosophical Society (and a correspondent of W.B. Yeats). Absorbed by traditions of Irish mythology and storytelling, in 1910 she produced this volume of stories — each of them quite short but diverse in their range and scope.

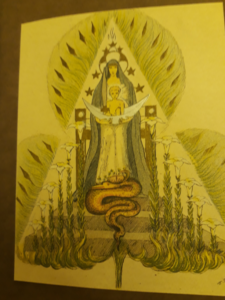

They were accompanied by illustrations made by her friend, Maud Gonne (1866-1953), the English-born Irish revolutionary, campaigner, and suffragette — and famously beloved by Yeats.  The volume was a labour of love which stemmed from the shared artistic and political interests of these two women. These in turn had grown out of the movement usually known as the Celtic Revival which had gathered energy from the 1880s onwards, building on earlier folk-collecting impulses and political movements to forge a new distinct sense of Irish vernacular culture, language, and identity (the National Literary Society was founded in 1892, for example; the Gaelic League in 1893).

The volume was a labour of love which stemmed from the shared artistic and political interests of these two women. These in turn had grown out of the movement usually known as the Celtic Revival which had gathered energy from the 1880s onwards, building on earlier folk-collecting impulses and political movements to forge a new distinct sense of Irish vernacular culture, language, and identity (the National Literary Society was founded in 1892, for example; the Gaelic League in 1893).

*

‘Afterwards there was a child born to the queen – a strange beautiful child, and the queen called her Ethaun. Every one in the palace loved the child and tried to please her but nothing pleased her for so long and as she grew older and more beautiful they tried harder to please her but she was never contented. The queen was sad at heart because of this, and the sadness grew on her day by day and she began to think her child was of the Deathless Ones that bring with them too much joy or too much sorrow for mortals…’ – from ‘The Golden Fly’

*

The stories in Young and Gonne’s book have been described as ‘highly simplified’; but that does not quite do justice to these pared-down, lyrical fragments of larger narratives. Any translation is, of course, an act of re-creation and re-interpretation; and the transformation of Irish language into English is always already a politically and culturally freighted thing.

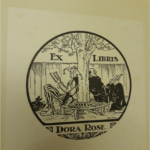

Revivalist romanticism permeates the volume — this can be recognised and understood, and the stories still appreciated for their arresting beauty and charge.  The book succeeded in bringing a new audience to these tales and inhabits that beguiling shadow-land — the threshold between ‘adult’ and ‘children’s’ literature which wonder tales can happily occupy. And we know that it once belonged to a girl called Dora Rose whose bookplate adorns this, and a good handful of the Museum’s books.

The book succeeded in bringing a new audience to these tales and inhabits that beguiling shadow-land — the threshold between ‘adult’ and ‘children’s’ literature which wonder tales can happily occupy. And we know that it once belonged to a girl called Dora Rose whose bookplate adorns this, and a good handful of the Museum’s books.

*

‘Midyir stretched his hands to Ethaun, and she turned to Eochy and kissed him.

“I have put into a year the gladness of a long life,” she said, “and to-night you have heard the music of Faery, and echoes of it will be in the harp-strings of the men of Ireland for ever, and you will be remembered as long as wind blows and water runs, because Ethaun – whom Midyir loves – loved you.” from ‘The Golden Fly’

*

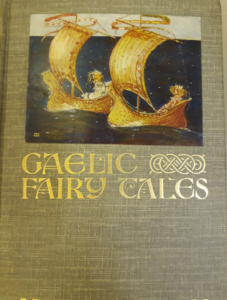

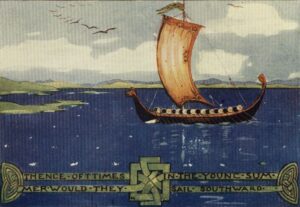

Three years earlier, in Scotland, a book called Gaelic Fairy Tales was published. This was a slender dove-grey volume with a striking cover: burnished Celtic-style lettering, and a vivid but dream-like image of two golden ships, with a bright-haired voyager in each.  It contained three stories — ‘Spiorad na H-aoise’, or ‘The Spirit of Eld’; ‘Iolaire Loch-Tréig’, or ‘The Eagle of Loch Treig’; and ‘A Bhean Tighe Mhath ‘s Obair-Oidhche’, or ‘The Good Housewife and her Night Labours’ — which were printed in Gaelic and facing English translation. These were adapted by a young woman called Winifred M. Parker (1879-1962), and published in aid of An Comunn Gàidhealach, founded in Oban in 1891 to support and nurture Gaelic language and literature, culture, and history.

It contained three stories — ‘Spiorad na H-aoise’, or ‘The Spirit of Eld’; ‘Iolaire Loch-Tréig’, or ‘The Eagle of Loch Treig’; and ‘A Bhean Tighe Mhath ‘s Obair-Oidhche’, or ‘The Good Housewife and her Night Labours’ — which were printed in Gaelic and facing English translation. These were adapted by a young woman called Winifred M. Parker (1879-1962), and published in aid of An Comunn Gàidhealach, founded in Oban in 1891 to support and nurture Gaelic language and literature, culture, and history.

Like its Irish successor, this little volume partly springs out of the folk-collecting movements of the previous century (John Francis Campbell of Islay and his team of collectors, for example, gathered nearly 800 tales from the Gaelic-speaking West Highlands which appeared as Popular Tales of the West Highlands (1860-2) (hailed as ‘The Arabian Nights of Celtic Scotland’).[1] It can also be set against the diverse energies and impulses of the Celtic Revival movement in Scotland, driven by Patrick Geddes and other artists, writers, and activists who sought to rediscover the aesthetic and spiritual ideals of Celtic art and culture. The year in which the book was published, for example, saw Edinburgh hold the meeting of the international Pan-Celtic Congress.

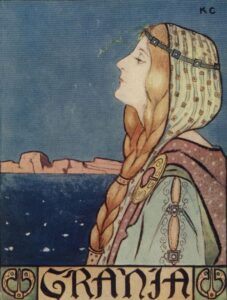

Gaelic Fairy Tales shows its sympathies for Celtic Revivalist art in its design and aesthetic. Parker’s visual collaborators were Rachel Ainslie Grant Duff (who also provided illustrations for J.F. Campbell’s The Celtic Dragon Myth in 1911], and Katherine Cameron (1874-1965). Born in Hillhead, Glasgow into a large family (her father a minister, her mother a painter too), Cameron had been part of the self-styled “Immortals”, a coterie of students from Glasgow School of Art which included Francis and Margaret MacDonald sisters. One of the ‘Glasgow Girls’ , according to Jude Burkhauser, she ‘drifted into book illustration because she was asked to’. She became pre-eminently an illustrator of children’s stories, including Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies, and of Arthurian legends and traditional ballads (‘ “She has the true race feeling of the Celt for love and legend … old ballads and fairy mysteries furnish most of her themes”’, noted one reviewer in 1900).[2]

*

‘They sought out a place, a hidden green spot in the forest. They made a house, and there they nurtured the child in secret. Year by year she throve and grew with them. Teigue brought her berries and taught her to play on a little reed flute. When she made music on it the wild creatures of the woods came about it. She played with the spotted fawns, and the king of the wolves crouched before her and licked her hands. Osric made a bow for her, and taught her how to shoot arrows, but she had no wish to kill any beast, for all the forest-reatures were her friends’ […] ‘Aidan told her stories. He told her how the sun changed into a White Hound at night, and Lugh the Long-Handed put a silver chain on it and led it away to his Secret Palace, and it crouched at his feet till the morning, when he loosed it and let it run through the sky again. He told her how Brigit counted the stars so that no littlest one got lost, and how she hurried them away in the morning before Lugh’s great hound came out to frighten them…’ from ‘The Luck-Child’

*

Another volume can be added to our kinship of books — one in which Katherine Cameron appears as the sole artist. So too does a version of the story of ‘The Children of Lir’ which had been included in Young and Gonne’s volume. Celtic Tales Told to the Children was evidently inspired by the same political and artistic forces which drove the Revivalists in both Ireland and Scotland — its preface acknowledges that it was inspired by various sources including those by Standish James O’ Grady, a key figure in the Irish Celtic Revival (an aristocratic unionist who celebrated and championed the heroic tales of Ireland), and Douglas Hyde, first president of the Gaelic League.

It appeared as part of a larger and popular series called ‘Tales Told to the Children’, devised by Louey Chisholm.  These were highly praised — they should ‘tempt even the least bookish of the little ones to start upon a voyage of exploration inside’ — though their original sources were diverse and sometimes far from obviously ‘child-like’ (such as Beowulf, Undine, and Dante)! Imaginative reinvention and creative adaptation is at work here too. There’s a triptych of tales — ‘The Star-Eyed Deirdre’, ‘The Four White Swans’, and ‘Dermot and Grania’ — condenses from much larger original story cycles.

These were highly praised — they should ‘tempt even the least bookish of the little ones to start upon a voyage of exploration inside’ — though their original sources were diverse and sometimes far from obviously ‘child-like’ (such as Beowulf, Undine, and Dante)! Imaginative reinvention and creative adaptation is at work here too. There’s a triptych of tales — ‘The Star-Eyed Deirdre’, ‘The Four White Swans’, and ‘Dermot and Grania’ — condenses from much larger original story cycles.

Love, desire, betrayal, jealousy, violence — these are the passions which drive their heroines and heroes. It’s an emotional and psychological universe which, fused with the ethos of a heroic warrior society, might not seem ‘tamed’ or adapted for a readership more used to moralistic children’s stories! But this is also the stuff of fairy tales, and this is the story-world most visibly rendered in this book. Exposure to any Grimms or Andersen collection (even the bowdlerised versions) would have made envious stepmothers, forbidden love, and persecuted children quite familiar to a young readership.

In the preface, Chisholm writes:

‘One of my friends tells me that you, little reader, will not like these old, old tales; another says they are too sad for you, and yet another asks what the stories are meant to teach.

Now, I, for my part, think you will like these Celtic Tales very much indeed. It is true they are sad, but you do not always want to be amused. And I have not told the stories for the sake of anything they may teach, but because of their sheer beauty, and I expect you to enjoy them as hundreds and hundreds of Irish and Scottish children have already enjoyed them – without knowing or wondering why.’

The emotional dynamic of these stories isn’t muted by Chisholm, and their heroines retain their power and strength. The secluded Deirdre longs for ‘a youth […] whose skin was white as snow, his cheek crimson as that pool of blood, and his hair black as the raven’s wing, him I could love right gladly’.  And Gráinne, who had directly chosen her beloved Diarmuid against the wishes of her father and with the aid of a magic drinking potion (‘it is from the champion who sat next to me that I have learnt thy name, but ere I knew it I loved thee’), starkly instructs her sons at the story’s end to avenge their father’s death: ‘I will myself portion out among you your inheritance of arms, of arrows, and of sharp weapons…’.

And Gráinne, who had directly chosen her beloved Diarmuid against the wishes of her father and with the aid of a magic drinking potion (‘it is from the champion who sat next to me that I have learnt thy name, but ere I knew it I loved thee’), starkly instructs her sons at the story’s end to avenge their father’s death: ‘I will myself portion out among you your inheritance of arms, of arrows, and of sharp weapons…’.

*

Our box sheds light on a cornerstone of early children’s literature, and on the criss-crossings between politics, tradition, culture, and language which fostered these beautiful books. The volumes raise particular questions about the role of appropriation, adaptation, and ideology — but these are not, of course, entirely new when we think about the history of children’s literature and the writers, cultures, and forces which have both enabled and stifled its emergence.

They are also testimony to the vitality, resilience, and endlessly ‘recyclable’ capacity of these stories, being made anew time and again for a different readership and audience. They show how visual and verbal realms go hand-in-hand — and just how striking women’s involvement, as writers, translators, and artists, was in the making of these books.

And this is only the surface of a deep wellspring of children’s literature — not just in Scotland and Ireland, of course — inspired by myth and traditional narrative which flourishes in the present. But that is a story for another day — and for our exhibition!

[1] Margaret Bennett, in The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Traditional Literatures, edited by Sarah Dunnigan and Suzanne Gilbert (2013), p. 9.

[2] Jude Burkhauser, Glasgow Girls. Women in Art and Design, 1880-1920 (2001), pp. 77, p. 220.

On Ella Young, see Rose Murphy, Ella Young. Irish Mystic and Rebel. From Literary Dublin to the American West (2008); W.W. Lyman, ‘Ella Young: A Memoir’, Éire-Ireland 8/3 (Autumn 1973); Sinéad McCoole, No Ordinary Women: Irish Female Activists in the Revolutionary Years 1900–1923 (2003).

On Winifred Parker, see Priscilla Scott, ‘”With heart and voice ever devoted to the cause”: Women in the Gaelic Movement, 1886-1914, unpub. PhD thesis (University of Edinburgh, 2013).

This post by Sarah, with kind thanks to Dr Kate Mathis