Introduction:

I used to be a mathematics teacher interested in creative practice and inclusive education. Based on my previous working experience and interests, I designed an art-based intervention for one-on-one math classes with ADHD students in 7-12th grade, including sensory art for middle school students and rhythmic/kinetic art for high school students. Inspired by Laura Aldridge’s sensory inclusion2, Andrea English’s educative listening3, and John Dewey’s ‘confusion as learning’4, this intervention also takes up some of the key datafication literature (like Neil Selwyn’s What’s the Problem with Learning Analytics?5 and Elana Zeide’s The Structural Consequences of Big Data-Driven Education6) to reshape those data-driven practices that marginalize neurodiverse learners. Below is my reflection in response to the feedback of instructor towards my blog and core course requirements.

1.Interdisciplinarity: Merging Theory, Neurodiversity, and Anti-Datafication

This intervention, then, can be powerful because it weaves creative practice with critical responses to datafication, which disproportionately does harm to students suffering from ADHD. Selwyn (2019)5 critiques learning analytics for reducing education to ‘proxy indicators’ (p.12, Section 3.1), flattening ambiguous, embodied learning into quantifiable data, which ignores ADHD students’ sensory-cognitive strengths of tactile engagement and dynamic thinking, that evade standard metrics. Zeide (2017)6 further warns of ‘techno-idealism’: the flawed belief that algorithms can solve educational inequities without accounting for neurodiversity (p.167, Equity).

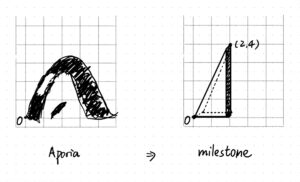

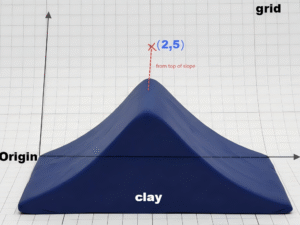

As Dewey (1933/1989)4 insists, learning benefits from puzzlement: ‘Reflective inquiry begins when we are puzzled’ (p.121). It can be relevant to Burbules’ (2015)7 aporia – doubt as a necessary passage to learning. The clue is, this sets the development immediately against Selwyn’s complaint5 of ‘reductionism’ in education (p.12). In the middle school ‘Pre-Algebra Terrain’ activity, an imaginary 8th grade student, fumbling with the adjustments of the clay slope to pass through a point (2,5), experienced tactile aporia (collapsed clay, too flat gradients) instead of being instructed ‘slope = rise/run.’ The guiding question by the tutor (‘How does the clay feel when it’s too steep?‘) encouraged exploration, and preserved for the student the qualitative experience of ‘feeling’ gradient-something data-driven tools cannot capture.

Farinati & Firth (2017)8 describe rhythmic listening as ‘a bridge between self and others’ (p.18). Against the techno-idealism of Zeide, for students with ADHD who struggle with verbal working memory, Barkley (2015)9 states, the adaptive platforms tracking ‘eye movement engagement’ do little to acknowledge the multiple sensory needs of diverse learners. Pairing staccato 2-beat rhythms with factoring, a sampling of the ‘Algebraic Beats’ high school activity, one 11th grader explained: ‘Factoring feels like quick steps-you catch the right terms fast.’ This merges sound art with math, relational building in its disregard for one-size-fits-all data logic.

2. Knowledge and Understanding: Unpacking Listening, Feedback, and Relationality

2.1 Nonverbal Observation as Educative Listening: Resisting Black-Boxing

English (2009)3 defines educative listening as attending to cognitive interruptions (p.72) – unexpected responses that reveal blind spots. The instructor’s feedback has nudged me to consider the relationship between tutor observation of clay use with this theory and Selwyn’s (2019)5 ‘black-boxing’ critique (p.12 Section 3.3): opaque algorithmic decision-making that disempowers students. For ADHD students, verbal expression is often difficult (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)1 – they may ‘feel’ clay is ‘right’ but can’t say why. A tutor’s observation of a 7th grader swapping soft or hard clay for a right triangle (‘You’re using hard clay for the hypotenuse – does it feel stable?‘) acknowledges problem-solving that wasn’t spoken. This transparent, context-aware practice resists data-driven tools dictating ‘next steps’ without explanation.

2.2 Feedback Rationale: Critiquing Coerced Labour

Instructor’s feedback asked why I avoided direct verbal feedback. This was rooted in ADHD communication needs and Selwyn (2019)5 ‘coerced labour’ (p.14 Section 4.2): students being forced to generate data for platform profit. ADHD students struggle with translating sensory experience into words, so questions like ‘Did the clay help?‘ yield a lot of vague responses that become exploitative data. Instead, the intervention uses proxy methods for the gathering of data, such as duration of engagement (aim≥15 minutes), creative output analysis, e.g. a slope passing through point (2,5), and also visual Likert scales. These studies respect how ADHD students communicate while resisting Zeide (2017)6 ‘pervasive surveillance’ (p.169) – with no third-party data collection, no permanent records of mistakes. Future iterations may include a ‘material journal’ (clay/pipe cleaner collages) to help bridge nonverbal and verbal expression.

2.3 Explicit Relationality: Countering Displaced Decision-Making

Relationality, as understood as mutual and empowering connections, is threatened by ‘displaced pedagogical decision-making’ (Zeide, 2017, p.169)6. In other words, teaching authority shifts from the public educator to private tech provider. This intervention rebalances powers in three ways:

- Tutor-student:Confirmation of material selections constructs trust – ‘Why sandpaper for negative slopes?’ – and inoculates against Zeide’s concern that data tools ‘constrain teacher autonomy’ (165)6.

Hypothetical Feedback: More student-initiated questions after activity

- Student-math:Art rehumanizes math – a 10th grade student called it ‘something I can play with’ – resisting Selwyn’s critique of ‘measurable-only indicators’ (p.12)5.

- Student-self:Validating the strengths of ADHD group (‘I’m good at building – math can be building too’) encourages self-acceptance, sidestepped by Zeide (2017)6 ‘computable competencies’ (170) that foreground quantifiable competencies.

3. Design Reflection: Challenges and Data-Driven Critiques

Hypothetical testing highlighted two major barriers: material accessibility through solving with household items such as playdough, and neurodiversity trainings for tutors.

Drawing on the literature on datafication, the intervention unpacks three critical harms:

- Data reductionism:Rejection of tracking ‘correct answer,’ qualitative experiences over quantification. This supports Selwyn’s call (18)5, for analytics that reflect lived reality.

- Permanent records:Does not record all errors; this protects Zeide’s ‘intellectual privacy’ (Zeide, 2017,165)6 and promotes the risk-taking needed to learn.

- Techno-idealism:Positions art as complementary, not a ‘solution’, acknowledging no single tool (digital or analogue) would resolve the needs of all neurodiverse

Supporting Resources*:

Three hypothetical resources can give rise to the intervention’s process.

a. Photos of Clay Terrain:Annotated images of ‘confusion traces’ (collapsed clay) and ‘milestones’ slopes through (2,5), illustrating Dewey’s aporia.

|

|

| collapsed clay | milestones slopes |

b. Algebraic Beats Audio:A 30-second factoring drumbeat with a material journal reflection, capturing one’s rhythmic listening.

b.1 Factorization beat

|

This beat is designed to map the core logic of polynomial factoring to rhythmic layers: find the greatest common factor (GCF) → split the middle term |

||

| Kick Drum | Finding GCF | Hit on the 1st and 3rd beats;

Set to strong velocity to represent this foundational, decisive first move in factoring that requires clarity. |

| Snare Drum | Trying to split the middle term | Fire on the 2nd and 4th beats.

Use medium velocity to correspond to splitting the middle term, while the 4th beat snare is softer to mimic verifying the split result- a quick check to ensure accuracy. |

| Rhythmic Cycle | Repetitive practice | Repeat for 30 seconds, aligning with the repetitive, step-by-step nature of factoring practice. |

b.2 Material journal reflection:

refer to the attached*: Supporting Resources (Hypothetical)

Adaptability Notes for ADHD Students:

- No writing is required; all expression is through hands-on collage, reducing executive function load.

- Sensory-focused: Draws on tactile/visual learning strengths of ADHD students.

- Simple choices: clear, concrete tasks, such as mold/bend, rather than open-ended demands. Low pressure: there’s no ‘right/wrong’way to create; this invites authentic expression free from feedback stress.

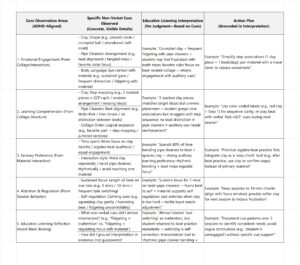

c. Tutor Journal Entry: Observation of non-verbal messages, showing educative listening versus black-boxing.(refer to attached *: Supporting Resources (Hypothetical))

Template Design Rationale:

- Observation Cues-Concrete: Prompts tutors to write down what they ‘see/hear’and should not assume anything, which is important in students with ADHD, since their non-verbal cues are far more reliable than their verbal responses.

- Educative Listening Focus: Forces separation of ‘cues’and ‘interpretation’ in order to avoid judgment, such as ‘frustrated’ versus ‘unmotivated,’ and centers the student’s non-verbal ”

- Action-forward: Each interpretation leads directly to a specific, modifiable action-no ‘dry’ observations-so the interventions would address the needs particular to ADHD: sensory, focus, and regulation.

- Anti-black-boxing: Section ‘Reflection’enforces transparency in that tutors should indicate how conclusions are based on evidence, eliminating unaccountable decisions.

4. Conclusion

This intervention design has made me deeply realize that inclusive education involves the need to reimagine practices from the perspective of neurodiverse strengths while remaining resistant to datafication tendencies. In this, abstract concepts of mathematics are turned into a sensory and relational experience. Interdisciplinary theories and creative practices amalgamate here, resisting jointly data-driven simplification, surveillance, and the displacement of authority. Future plans for improvement will involve adaptable materials and student-led feedback tools, but the crux remains the same: education must empower rather than pathologize. As Aldridge (2022)2 expresse, ‘Make space for everybody’. In this way, we resist not only the narrowing of educational datafication, but we also enrich outcomes for all.

References:

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA.

- Aldridge, L. (2022). ‘Make space for everybody, make time for difference.’

- English, A. (2009). Listening as a teacher: Educative listening, interruptions and reflective practice. Philosophical Inquiry in Education, 20(1), 69–82.

- Dewey, J. (1933/1989). How we think. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Selwyn, N. (2019). What’s the problem with learning analytics? Journal of Learning Analytics, 6(3), 11–19.

- Zeide E (2017) The structural consequences of big data-driven education. Big Data 5:2, 164–172, DOI: 10.1089/big.2016.0061.

- Burbules, N. C. (2015). Aporias, webs, and passages: Doubt as an opportunity to learn. Curriculum Inquiry, 45(2), 171–190.

- Farinati, L., & Firth, C. (2017). The force of listening. Errant Bodies Press.

- Barkley, R. A. (2015). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

*: Supporting Resources (Hypothetical)

- Clay Terrain Photo Series: student-created algebraic landscapesgenerated by following sketch.

- Algebraic Beats Audio Clip: Drumbeat composition+ material journal reflection

Drumbeat composition tool: https://www.soundtrap.com/

Material journal reflection template:

- Tutor Reflection Journal Excerpt: Nonverbal cue observations