Does the Ed-Tech Sector Offer a Valid Diagnosis of What’s Wrong with Education?

To address whether the Ed-Tech sector solves what’s broken in education, we must first ask: What, if anything, is wrong with education? Who better to answer this than students and teachers? In my role at an EY12 international school, I interviewed five educators (from Early Years to Grade 12) and five students. The responses were surprising as they were concerted: education, as it stands, is fundamentally flawed.

What’s Wrong with Education?

“All of it.”

This honest remark from an educator summarises the opinions shared across my interviews. Every participant agreed that there are deep-rooted problems in education. Their feedback paints a stark picture, revealing gaps that go far beyond the surface-level imaginaries that Ed-Tech companies claim to address.

What Students Said

Students voiced dissatisfaction with the traditional classroom structure. “School is boring,” they said. “It’s the same thing every day.” They didn’t speak about technology or the benefits touted by Ed-Tech platforms. Instead, they longed for more time outdoors and yearned to learn practical skills that could prepare them for their “life in the real world”.

What Teachers Said

Teachers, on the other hand, critiqued structural and systemic issues. They described schools as “transactional places” that fail to reflect how students like to learn or what they actually need. One teacher lamented, “We’re conforming students into a sausage-making factory, pushing them through curricula designed decades ago.”

They pointed out that the rigidity of educational systems ie. “condensing two years of knowledge into a four-hour IB exam, leaves no room for life skills or experiential learning”. Teachers didn’t highlight administrative inefficiencies; instead, they spoke about being “hamstrung by structure” and the absence of meaningful, real-world learning opportunities. Additionally, none of the teachers I interviewed voiced how efficient their roles had become due to Ed-Tech tools. In fact, one teacher raised a crucial concern: “If teachers aren’t doing their own assessments or writing reports, how will they ever learn more about the child intuitively or sharpen their own skills? Teachers will regress.”

Technology Begins Beyond the Screen: A Teacher’s Perspective

In a conversation with an Early Years teacher, they shared a perspective that struck at the heart of the education-technology debate: “The whole point of technology and innovation doesn’t start with a screen. It starts with exploration.” This simple yet profound statement contradicts the Discursive Construction (Selwyn 2015) phenomena when we talk about ‘Digital Technology and Innovation’ and encapsulates what Ed-Tech often overlooks.

“True innovation in education begins with brainstorming, creativity, and physical activities. It starts with children drawing on paper, playing and engaging with the world in tangible ways—long before any digital tool is introduced”. This process nurtures critical thinking, imagination, and problem-solving skills (Nussbaum 2010).

Despite their advancements, Ed-Tech companies cannot replicate the deep care and nuanced understanding that teachers bring into the classroom. A digital platform might collect vast amounts of data and present it in pretty, colourful dashboards, but it will never comfort a struggling student or understand the unspoken needs of a learner. Ed-Tech companies feed on continuous data —numbers and metrics designed to identify patterns. What it cannot replicate is the human experience.

Moreover, teachers were significantly concerned about Ed-Tech companies monopolising education and creating imaginary narratives (Markham 2005) that force educators to rely on their technology. Like most schools, we identify ourselves as a ‘Google’ and ‘Apple’ school. Via peer and social pressure Ed-Tech companies are embedding their tools into schools and collecting huge amounts of private information on children, including personal information. One teacher questioned the long-term implications: “Will they then be able to train students into learning things outside the scope of the curriculum? Things teachers don’t want them to learn?” This raises the alarming possibility that AI could begin controlling the narrative of education, leading to discursive closure where no alternatives to AI-driven improvements seem possible. The hidden curriculum may indeed be truly hidden, from teachers themselves.

Ed-Tech’s Diagnosis: What Does It Say Is Broken?

At my school, we recently implemented Toddle, a Learning Management System (LMS) designed to make teachers’ lives easier. Toddle’s key offerings include:

- Saving teachers time by streamlining assessments and planning.

- Bridging communication between school and home.

- Providing students with AI-powered, individualised learning support.

While these solutions improve efficiency, they don’t address the deeper concerns voiced by students and educators. The imaginaries promoted by Ed-Tech—personalised AI learning, automated reporting, and instant communication—assume that the “how,” “what,” and “when” of education are fine. However, my findings challenge this assumption.

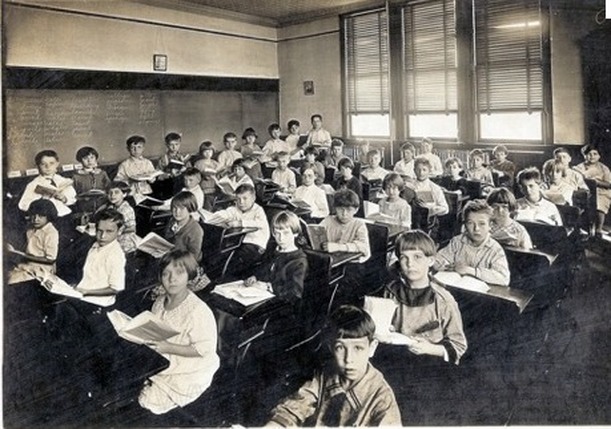

- How: Are traditional classrooms the best environment for learning? Students clearly desire more experiential and outdoor learning opportunities. As can be seen by the pictures below, nothing has really changed from the 1800 to the year 2000 except for books being replaced by laptops.

VS

VS

Copyright: Weebly.com Copyright: The Sunday Guardian

- What: Why are we adhering to a curriculum that hasn’t evolved in decades (dare I say, a century)? Life skills like cooking, managing finances, and understanding taxes are largely absent.

- When: Why do we still follow an academic calendar based on 19th-century agricultural schedules?

Child Labour in Lancaster Cotton Mills Credit: The Social Historian

Ed-Tech’s Misalignment

Educational theorists like Biesta emphasise that schooling should go beyond mere qualification. Yet, many students graduate without understanding basic life skills. Instead, the system prioritises rote memorisation and standardisation. The word ‘business’ came up several times with the educators I interviewed. They felt that schools were now educational corporations, selling university destinations and money making careers to children rather than a place that teaches them how to find their place in the world whilst adding value to society (Nussbaum 2010).

Conclusion

The Ed-Tech sector, for all its new and helpful functions, has misdiagnosed the root problems in education. It offers solutions to peripheral challenges—efficiency, communication, and assessment—while ignoring the core issues of outdated curricula, rigid structures, and a lack of practical, real-world learning.

Ed-Tech has truly interrupted the Education sector (Biesta) however, I would replace Suspension and Sustenance, with what Ed-Tech has actually created, which is Diversion and Delay in actually tackling the real problems of what is broken in education. In fact, I would go as far as saying, Ed-Tech has created a whole plethora of new problems in education to add to it’s existing list!

If we truly want to fix a broken system, we must shift our focus. Technology can support education, but it cannot redefine it. That is up to us.

Hello Nishe,

Great multi-modality you provide to represent the various dimensions of what is broken.

I like the questions you raise for example… “whether the Ed-Tech sector solves what’s broken in education, we must first ask: What, if anything, is wrong with education? Who better to answer this than students and teachers?

I agree with your position that “Technology can support education, but it cannot redefine it. …that is up to us”.

The evidence you provide from the interviews with teachers and students, is representative of the current debates and discourses around what is broken in the education system. You should also refer to what your peers have shared in the forum posts to enrich your argument.

I should add that, the Edtech sector, diagnosis to the pain points of the systems promotes underlying values that perpetuate and legitimate certain structures, infrastructures and tools that reproduce existing challenges in the sector.

It is important also to analyse these underlying values promoted by the discourses of digital education, such discourses of “reschooling and deschooling” and how they contribute to legitimation of tools and infrastructures, e.g., laptops in classrooms…in the place of books…..

More so, effective diagnosis of the education system challenges would need to address the power, resources and agency issues through a critical discourse analysis of education and digital technology practices, processes, tools and, including a comprehensive actor network analysis.

While this reference was for further reading, Pischetola (2021) highlights three flawed perspectives—Techno-Determinism, Techno-Solutionism, and Techno-Instrumentalism—that challenge us to critically evaluate how we integrate ed-tech into our curriculum. These three concepts also provide a useful framework to evaluating our use of technology in provision of education.