Reflecting on our field trip, it becomes clear that exhibition curation is not merely about the selection and arrangement of artworks but also about the underlying narratives, power structures, and institutional intentions that shape audience engagement. While each institution we visited employed distinct curatorial methodologies, they also revealed broader issues related to representation, accessibility, and the politics of display.

A Powerful Tool or the Risk of Aestheticizing Trauma?

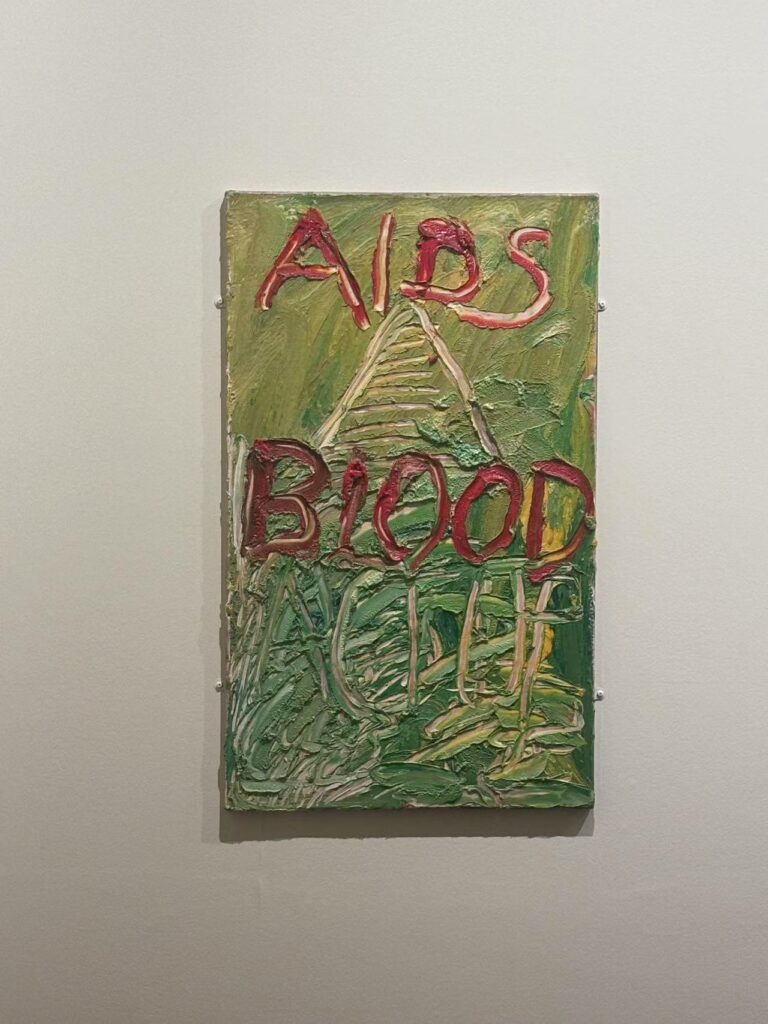

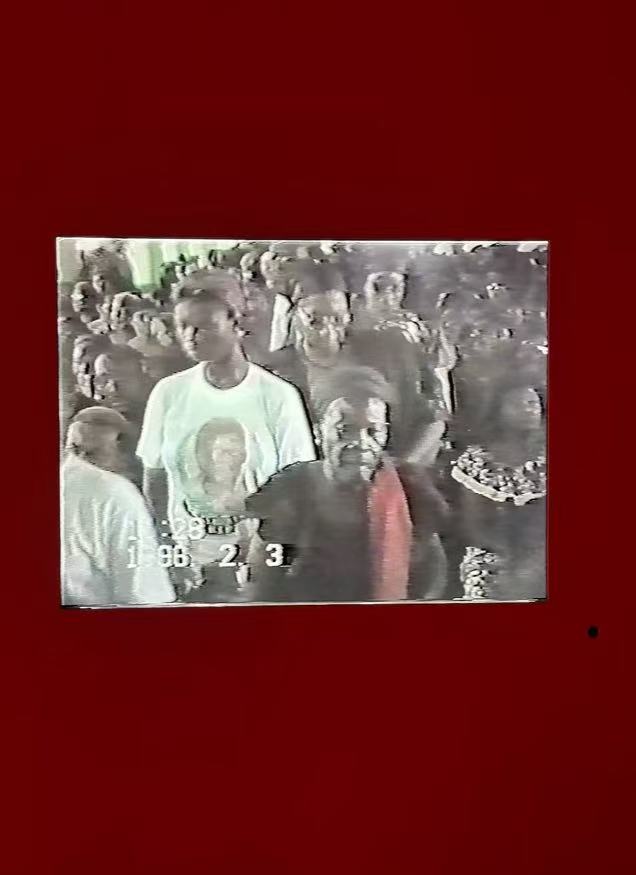

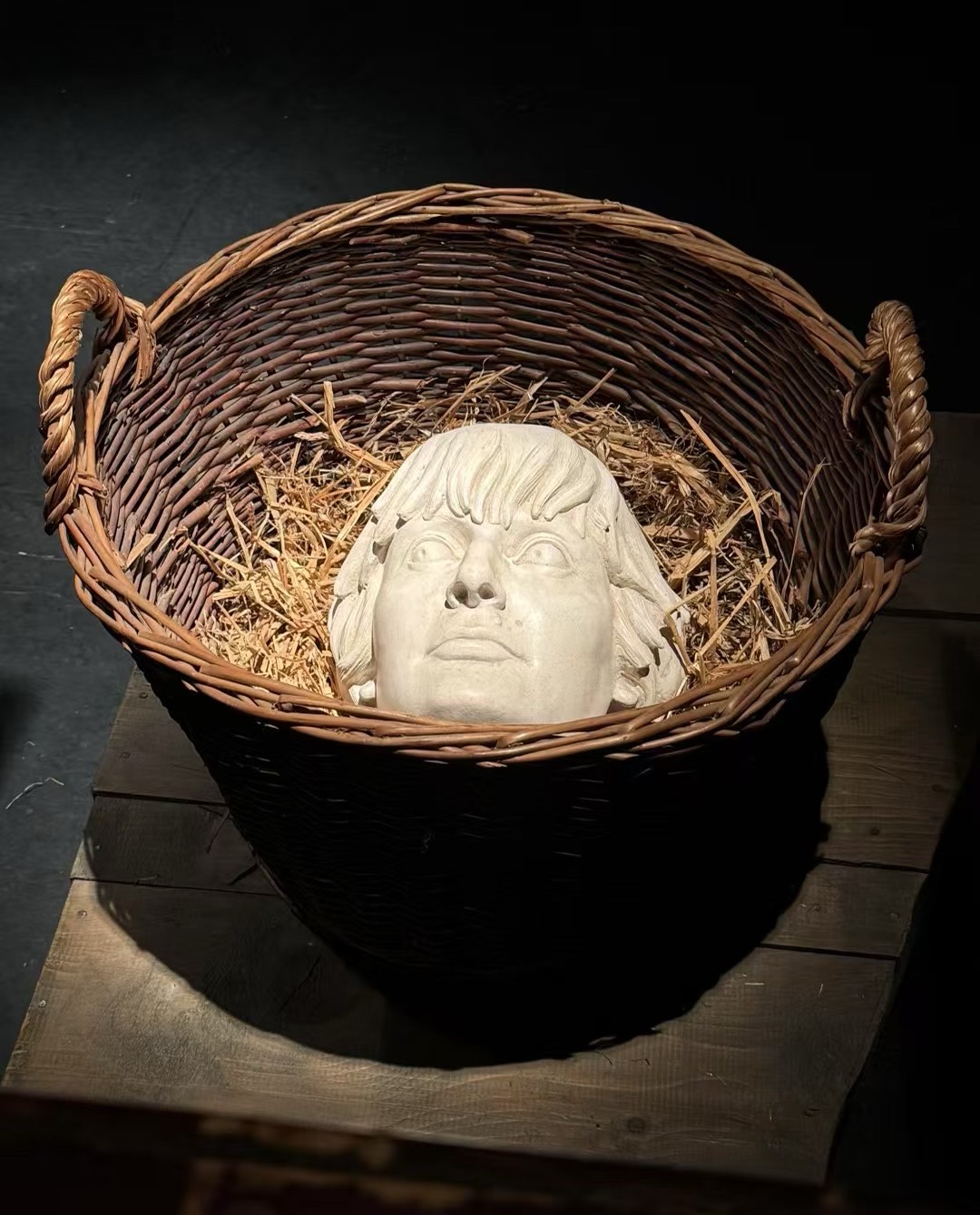

Walking through The Hunterian’s exhibition on Jarman, I was struck by the way archival materials—newspaper clippings, photographs, and personal writings—were used to frame his work. The display was undeniably powerful; the juxtaposition of media sensationalism with deeply personal narratives created an emotional and intellectual tension that made me reflect on how history is told and whose voices are amplified. The choice to present Jarman’s activism through an archival lens gave the exhibition a strong historical grounding, reinforcing his political fight against AIDS stigma and LGBTQ+ marginalization. However, it also raised a more complex question for me: does presenting trauma through carefully curated archives risk making suffering an aesthetic experience for audiences removed from that reality?

Hal Foster (2015) describes archival curation as “a form of counter-memory,” challenging dominant narratives by foregrounding marginalized perspectives. This was evident in how the exhibition placed Jarman’s work in direct conversation with the media’s representation of AIDS in the late 20th century. Yet, as I moved through the space, I couldn’t help but question whether the very act of exhibiting these materials—placing deeply personal pain within a gallery setting—could distance audiences from the urgency of the issues they represent. Bennett (2022) warns that while such presentations can be deeply moving, they can also risk turning political struggles into consumable, academic objects rather than calls to action.

This tension between historical documentation and emotional engagement left me reflecting on the role of archival curation in contemporary exhibitions. While it is a powerful tool for reclaiming suppressed histories, it also requires careful consideration to avoid aestheticizing trauma.

Curatorial Reflections on Ethnography and Artistic Representation

This semester, in addition to my curatorial studies, I have been taking an Anthropology course, where we explored ethnography as a way of studying and representing different cultures. This made me think more deeply about how exhibitions like Maud Sulter’s are framed in institutional spaces. Sulter’s work celebrates Black female identity through powerful visual and textual storytelling, making it a strong example of cultural resistance. However, as Nash (2020) points out, museums and galleries often present Black artists in ways that focus mainly on their identity rather than their artistic style or concepts.

In anthropology, we discussed how ethnography has historically been used by Western researchers to study other cultures, sometimes reinforcing stereotypes or treating communities as “subjects” rather than equals (Clifford & Marcus, 2010). This connects to curatorial practice because exhibitions can sometimes unintentionally create the same effect—positioning artists like Sulter in a way that highlights their racial or cultural background more than their artistic innovation. This made me question: does curating work about race and identity in an institutional space risk making it seem like a cultural study rather than appreciating it as an artistic statement?

This reflection made me realize that representation in museums is not just about including diverse voices, but also about how those voices are framed. As Butler and Athanasiou (2013) suggest, identity is not a fixed category but is shaped by the way it is positioned within institutional and social structures. This highlights an important curatorial responsibility: to create a space where identity is acknowledged but not reduced to a singular narrative, allowing for more layered and complex engagements with the work.

This field trip deepened my awareness that curation is not merely about displaying art but rather a form of narrative construction embedded with ideological and historical dimensions. The spatial organization of exhibitions, the logic of presentation, and audience engagement are all shaped by broader institutional frameworks, cultural histories, and societal expectations. As I develop my own project, these reflections prompt me to consider how to balance visual and interactive experiences, how to maintain curatorial intent while allowing room for audience interpretation, and, most importantly, how to avoid unconscious biases in the curatorial process to create a truly multidimensional and open platform for dialogue.

References:

1. Foster, H. (2015) Bad new days : art, criticism, emergency. London ; Verso.

2. Bennett, J. (2022) Empathic vision : affect, trauma, and contemporary art. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

3. Nash, D. (2020). ‘The Ethics of Representation in Contemporary Curating: Institutional Framings and the Politics of Display’, Journal of Curatorial Studies, 9(1), pp. 45–61.

alewisj

4 April 2025 — 13:12

Your blog post in week 4 is very detailed and provides evidence of critical reflection, research and referencing. This sets you up with a great foundation for your project.

It’s great to see you recognizing and addressing key points at the early stages of your project, such as structural clarity, audience interaction, and technical feasibility. By acknowledging these areas, you can save time and determine whether an idea is viable. This demonstrates excellent forward-thinking. However, is it realistic and achievable to create an audience-interactive video work within a budget of under £10,000?

Your visit to Frame was successful in terms of gaining actual experience of the type of exhibition you have been researching. However, given the budget restrictions for this project, it feels unrealistic to have this kind of exhibition.

In week 6, you started asking questions about your project and relating them back to the lessons learned from the lectures, which is great to see. However, I noticed that you have been using the same references for the last few posts. While it’s beneficial to revisit key curatorial concepts and ideas, it’s also important to incorporate new theatrical references as the weeks progress and your project and curatorial knowledge expand.

In week 7, you asked some challenging and important questions related to the ethics of curation. It is clear that you have a thoughtful and considerate approach to this process. This also demonstrates your ability to be self-reflective and critical of the research you are conducting. Additionally, it was great to see you include some new references.

As you have missed a few tutorials, I wanted to check in and ask if you have any questions? It is important you refer to the learning outcomes and course guidelines so that you submit an achievable and realistic project. Below, I have posted a link to JL ‘s slides, which help break down what is expected of your individual projects and blog posts.

To enhance future blog posts, refer to JL’s slides presented this week, as they break down some of the subheadings.- https://www.learn.ed.ac.uk/ultra/courses/_117082_1/outline/file/_11117495_1

In particular, you might find this slide useful when editing your blogs

For every Blog Post: ask yourself how can I connect this with the 11 weeks of lectures and learning, the themes, and the course resources?

• A reminder to look at the reading list on Learn for extra resources.

• You must include your independent research and course materials.

• Exhibition research, and the curatorial texts from named exhibitions, are a

key part of this material.

• Caption images and list resources with full bibliographic/reference details.

Date, medium, materials, location, source etc. Do this consistently.