Changes in the Image of Chinese Women —— The Period of Division (220–589)

The Period of Division (220–589):From Three Kingdoms (220 – 280) and the Western Jin (265 – 317) to the Northern and Southern Dynasties (317 – 589)

Characteristics of dress:

During this period of frequent regime changes, the clash between the northern nomadic tribes and the Central Plains Han culture fostered cultural integration, while the rise of Neo-Daoism and the spread of Buddhism reshaped social thought. These factors collectively shaped women’s clothing with a dual character of “ethereal elegance” and “Hu-Han fusion.”

In terms of form, the traditional deep robes of the Han dynasty, known for their solemnity and complexity, were replaced by looser, more flowing silhouettes. Women often wore “zájū chuíshāo” (杂裾垂髾), garments adorned with layers of silk ribbons at the collars, cuffs, and hems. As they walked, the ribbons fluttered like drifting clouds, exuding an almost otherworldly grace. However, this style also reinforced the image of women as delicate and ethereal beings.

Influenced by the northern nomadic “ku-jū” (袴褶) attire, narrow-sleeved, cross-collared tops became increasingly popular. Han women, however, adapted this style by pairing it with broad lower garments and a cinched waist, preserving the practicality of nomadic clothing while maintaining the elegance of traditional Han attire.

Silk remained the dominant fabric, emphasizing lightness and fluidity. Textile patterns featured Buddhist motifs such as lotus flowers and acanthus, interwoven with traditional auspicious cloud patterns. The use of tie-dye techniques like “jiǎoxié” (绞缬) created a misty, watercolor-like effect on garments, resembling the soft diffusion of ink on paper. The contrast and fusion between northern and southern styles not only reflected cultural exchange but also highlighted the evolving representation of women’s identity in different social contexts.

Restoration of the attire of the Western Wei Dunhuang feeders

Hair style characteristics:

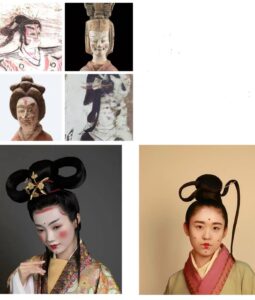

During the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, women’s hairstyles were characterized by “lofty elegance and cloud-like fluidity,” reflecting the era’s admiration for Neo-Daoist discourse and the pursuit of transcendence. Women styled their long hair into towering “cloud-like” chignons, either slanted or high-piled, often shaped like floating celestial figures. Their hair was adorned with golden foil floral ornaments, dangling step-shaking hairpins, and gemstone pendants, which shimmered and trembled delicately with each movement, resembling drifting clouds or soaring dragons.

Among aristocratic women, “Ling-snake chignons” (灵蛇髻) and “Celestial chignons” (飞天髻) were especially favored—intricately coiled and winding, resembling the sinuous curves of a serpent or the luminous halo of a Buddha, subtly echoing the aesthetic influence of Buddhism’s eastward spread. In contrast, common women often wore “Twin-loop chignons” (双鬟髻) and “Cranes-in-flight chignons” (惊鹤髻), securing their hair with delicate silk ribbons that cascaded gracefully, evoking a rare sense of lightness and elegance amidst an era of turbulence.

Celestial chignons (飞天髻)

Makeup:

The makeup of women during the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties blends chaos with elegance, creating a “non-human” aesthetic. Influenced by Buddhist iconography and metaphysical discourse, the makeup shifted from the plainness of the Han Dynasty to a more intricate and delicate style known as “Buddhist makeup.” Women applied lead powder to their faces, with yellow hues sweeping across their cheekbones. The forehead was adorned with vermilion or gold leaf, and the eyes featured a slanted red line. Lips were tinted in sandalwood color, with “dimples” drawn at the corners, creating an otherworldly, sacred look. Some women even attached delicate cicada wings to their cheeks, evoking the image of a spirit. The stark contrast between ghostly white faces and vivid red accents reflected both a rebellion against social norms and an allusion to the impermanence of life and death, embodying a unique form of facial artistry from that era.

Artefacts and restoration make-up

Conclusion:

The evolution of women’s clothing during the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties reflects the complex aspects of women’s status in a tumultuous era. Amidst intense social upheaval and the collision of multiple cultures, women, while not breaking free from the traditional moral framework, gained unprecedented space for aesthetic expression through their attire.

The fusion of Han and Hu styles in clothing (such as the combination of narrow sleeves and wide skirts) subtly hints at women’s passive involvement in social reconstruction during ethnic migrations. Meanwhile, the flowing skirts, draped hair, and Buddhist-inspired makeup reflected how women actively used their bodies as a canvas, infusing their daily attire with religious sanctity and metaphysical transcendence. This “wild” aesthetic practice was, in fact, a soft breakthrough for aristocratic women, who used their clothing to subtly challenge the constraints of traditional norms—transforming the ethereal beauty of their garments into a form of resistance, replacing political authority with forehead decorations, and quietly reshaping gender qualities within the wave of Buddhist secularization.

However, beneath the luxurious garments, traditional discipline still lurked: the “non-human” quality of makeup elevated feminine beauty to a divine level while also objectifying women as symbols of intellectual melancholy in chaotic times. The flowing nature of the attire ultimately derived from male metaphysical thought, rather than being a true expression of gender awakening. This contradiction encapsulates the position of women during the Wei Jin period—both as carriers of cultural fusion and as reflections of male elite aesthetics, blooming briefly and brightly in the fissures of history, creating a momentary freedom of aesthetic expression.