TAKING POWER, TAKING RESPONSIBILITY

The Presence & Absence of Community Participation in Ecocity Potential

Since the latter half of the 20th century but more increasingly since the turn of the millennium, there has been an increasing focus on sustainable development and the creation of ecocities as a response to environmental challenges. There are two main approaches to the ecocity – transitioning existing build, and new build.

Transitioning ecocities tend to be more sustainable than new build ones, as they have the advantage of building upon existing infrastructure and systems.This allows for a more efficient use of resources and a smoother transition towards sustainability. New build ecocities, on the other hand, incite a greater cost in terms of financing, energy, and carbon footprint for construction.They have the advantage of starting from scratch and implementing innovative and cutting-edge sustainable technologies and designs, however, and these cannot be overlooked.

This post will investigate the efficacy of ecocities through the lens of community participation – does the ‘sustainability’ of an ‘ecocity’, so to speak, increase or decrease, depending on whether the planning of the area has in some way involved, or evolved due to, community participation? Alternatively, is community par- ticipation essential to the success (sustainable or otherwise) of an ecocity?

To analyse the data and answer the question, however, another question may arise:“What is sustainability in this context?” A leadup, “For that matter, what is an ecocity?” Perhaps even, “On what foundations is ‘com- munity participation’ being defined?”

For clarity on these terms and the base concepts this report will discuss, the definition section may be found below.

Definitions

Sustainability In a contemporary urban context, sustainability can be said to be the pursuit of an integrated ‘development of economic, social and environmental subsystems mutually reinforcing different aspects of the urbanization process.’ While there are other definitions of sustainability, this one has been chosen for the purpose of this report, as it best fits the measures of city sustainability performance that will be assessed in the latter half of this investigation.

Ecocity The term was coined between 1979-1980, and has since been used interchangeably with sustainable city and green city, and is recognized as a city that is ‘organized to enable all its citizens to meet their own needs and to enhance their well-being without damaging the natural world or endangering the living conditions of other people, now or in the future.’

Ecocities are said to have, among other qualities, the following attributes relevant to this investigation:

- affordable, safe, convenient, and economically mixed housing;

- nurturing of social justice, creating improved opportunities for the underprivileged;

- promoting simple lifestyles, discouraging excessive consumption of material goods;

- increasing public awareness of the local environment through education and outreach

In other words, an ecocity can be said to be a just city. To be just is to envelope an incredibly broad scope, however. In the context of a city, justice looks into the systemic flaws of the inequality, division, and segregation integrated not only in education, industry, politics, and applications of religion, but that are made constitutionally tangible through policymaking and planning of the city, but also in the way ‘green orthodoxy’, whether well-meaning or purposely ignorant, can cause issues of environmental injustice – the ecocity must address these flaws with fair, accessible and equitable solutions.

There is also the oft-posited question in ecocities regarding justice and greening – for whom is this? Justice in such a city is and should be for the underprivileged and the marginalized, be it because of class, race, or other factors.

Justice As such, the working definition of justice enveloped within an ecocity’s inherent sustainability may be defined as one that examines the relationship between all groups of people present in the city, and their differing levels of access to resources, transforming the ‘deeply unjust urban landscapes’ into ones where all residents are on equitable footing to invest in (green) development, enjoying the ecological progress of the city and helping shape the sociopolitical context without the exclusion of any individual.

Community participation An extension of justice, or as is Schlosberg’s theory, one of the three forms of justice, community participation exists in a context where power is genuinely in the hands of the people, and is the meaningful and equitable bottom-up contribution by affected communities to regulatory, planning, policymaking and/or other executive processes of cityplanning, placemaking, and/or related actions. Without community participation, green orthodoxy may prevail, widening green gaps, increasing injustice to marginalized communities – the very opposite of ecocities set out to achieve.

Green orthodoxy A pervasive phenomenon orchestrated with government and privatized actions in tandem (the result of decades of citizen welfare being outsourced to private corporations. Now, privatized, profit-hungry logic is applied to all dimensions of life and society, where it cannot and should not be applied, and have thus created our current, capitalistic regimes with its many deep flaws), to form an unsustainable ‘ecobubble’ as opposed to an eco-city. In ‘ecocbubbles’, greening further benefits a privileged demographic that has consistently enjoyed increasing benefits (such as energy, health, and food) from the city from the past until the present, at the constant expense of the lesser privileged demographic, whose enjoyment of benefits has been consistently decreasing from the past until the present. Green orthodoxy thus creates a ‘green gap’ of privilege regarding green benefits, one that is rarely seen or otherwise addressed, giving rise to a ‘green mirage’.

“The government says, ‘that is not allowed, because we decide what the logic should be’ (…) We get stuck in a bureaucratic mill that does not allow us to take our own

responsibility.’”

(Interview with a board member of a Dutch community energy initiative.)

Case Studies

Masdar

City type New build

Community Participation Absent

While Masdar may have held the promise of an ecocity with zero carbon and zero waste almost two decades ago, it has since realized the scientific impossibility and the unrecoverable financial toll such a promise entails. Barring a breakthrough that either modifies or negates the Second Law of Thermodynamics, zero carbon and zero waste, whether with today’s technology or tomorrow’s, is a fantasy.

The facts: despite Masdar planning for almost 100,000 residents, half of which would be fixed, circa 2023 it has managed to house only 5,000. It is not the complete city, replete with mixed residential living it set out to be – instead, it is a commercial center and

research hub, in a desert development 80km away from the nearest city.

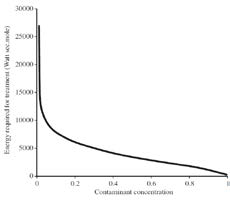

[Figure on left taken from Faber, M., Horst Niemes, & Stephan, G. (2012). Entropy, Environment and Resources]

[Figure on left taken from Faber, M., Horst Niemes, & Stephan, G. (2012). Entropy, Environment and Resources]

Regarding waste treatment, the incremental steps of purification take exponentially larger sums of money to complete, with each step producing its pollutive byproducts. Regarding carbon, Masdar built up a substantial carbon debt just by being constructed – and was not able to pay it off.

Originally meant to cover 7km2, the masterplan has been reduced to approximately half that area, with only a sixth of that having been constructed so far.10 It was set to reach completion in 2016. It cost $22 billion. It hasn’t been worth it – once dreamed to be a full- fledged, self-powered ecofriendly haven capable of treating all waste onsite, it now imports coal-powered energy from Abu Dhabi, and exports electronic waste and emissions elsewhere. This does not break boundaries, or provide new and unheard-of modes of sustainability – Masdar has recreated the same city with the same issues seen almost anywhere else on the globe (although perhaps with more financial loss).

While the vernacular urban planning and architecture do good work and set an example for success in turning back to traditional, local design strategies, the low-storey buildings and narrow, shaded streets host only the privileged: those adept either with business or science, with the funding to prove those claims. For whom is this green city? For whom do the solar panels of Masdar struggle to harvest energy through the dust clouds? When daily life is pictured in Masdar, there is rarely, if any, evidence of the lesser privileged demographic of the UAE benefiting from the institution. Masdar is a city for the privileged, started with privileged investors who, upon realizing the lifestyle choices one must change to make Masdar possible, backed out of the project and left it without a set date of completion, without the residents it was promised, without the success it aimed to achieve. The public policy of Masdar may have attempted to ‘get people to do things they might not otherwise do’, but did not take into account that many of the people, in the face of stark and abrupt changes, ‘lacked incentives or capacity to take the actions needed,’ or ‘disagreed with values implicit in the means’ to the end.

Masdar’s planning and following of green ideals and sustainable goals was, to all extents and purposes, purely prescriptive. It was built and has succeeded in being a ‘model’ city, where things appear exemplary, and function well, but not necessarily well enough to receive residents and convince them to stay. That would have been possible had it been treated less like a configuration of different, experimental ‘cutting-edge’ technologies, and more a place meant for humans. That would have been possible had it involved community participation, from residents it wanted to attract: the ones belonging to mixed residential units, the ones from all walks of life. The ones who may not be able to afford benefiting from green solutions elsewhere – that would have been an ecocity. That would have been just. Instead, the ‘ecobubble’ has now been created, at the expense of the construction workers, manual laborers, cleaning staff, invisible back-of-house maintainers who make Masdar possible and beautiful for the few who enjoy it, with its carbon debt, exported waste, failing solar power generation, and all.

HafenCity

City type New build (close proximity to existing build of Hamburg)

Community Participation Present, after construction

It bears repeating that the construction of new build ecocities in itself can have detrimental effects on the environment: building new infrastructure, clearing land, and disrupting natural ecosystems to make way for these ecocities can result in significant environmental damage, and the resources and energy required to construct these cities, even with a focus on sustainability, can only add to the negative impact.

Still, HafenCity Hamburg GmbH, the development company in charge of HafenCity, carried out extensive research and went through with the construction. Since the location of HafenCity is very close to the pre-existing building environment of Hamburg, the potential harm of HafenCity’s construction decreased.

Similar to the inception of Masdar, HafenCity began as more of a government and developer vision, with projections and estimates, than a provider of solutions to a problem residents were facing. In addition, while Masdar was started as a project of sustainability for the sake of sustainability, HafenCity is driven purely by market investment. HafenCity’s prominent focus is its being a commercial success, leading to its function as a primarily ‘commercial’ downtown, with only a fraction of its area for resident housing.

As far as citizen experience goes, HafenCity did not attempt to challenge Germany’s lack of social mix policies, as it is not included under national urban development goals, and thus not as prioritized as other policies by municipalities, which act independently outside of the national goals. Although they are actors at a large scale, the local governments’ divided attention does not impact social mixing’s absence from the country’s political infrastructure.

In fact, with no policy in place for social mix, and no funding for subsidised house building, the ‘route to a distributive form of social mix for residential households was doomed from the start’. This could go either of two ways for the structure of the community:

- a coincidentally socially mixed community by-product due to economic efficiency of HafenCity,

- a ‘mental gated community’ of privileged residents with clear, restrictive boundaries around the spaces of their activities, where even public spaces may be treated as an extension of their privately owned ones.

At best, HafenCity has been said – even in potentials and estimates – to have a limited social effect on the emancipatory aspect of the city. This will be explored further in HafenCity’s approaches towards initial masterplanning, participatory planning, and community participation.

Initial masterplanning The development company, not involving potential residents at this stage, opted to carry out extensive research, which can be seen in the literature surrounding its approach towards making social mix possible despite no policies for it, as well as its numerous calculations to create social encounter (daily ‘bubbles of opportunity’ where individuals may encounter people from diverse, different backgrounds, as a stand-in for otherwise somewhat homogenous living arrangements).The present and future of HafenCity are carefully dotted with ‘potentials’ – potential timings, potential actors, potential categories of potential events, and potential areas of social encounter.

Participatory planning Once HafenCity was constructed and residents had moved in, the development company networked families with young children to assist in planning the first playground, later passing its ownership onto the parents. While this does somewhat align with concepts of ‘community ownership’ and its positive implications for a city, HafenCity could have considered this approach earlier, to accommodate said families, and have the playground built earlier.

Another point that can be raised about this singular incident of participatory planning is that it is not community participation.The company frankly requested a playground and initiated its design process.This was still a top-down approach, not a bottom-up one.

Community participation While community participation has taken place in later stages of HafenCity’s development – the purpose it has been incorporated in is for revision of the masterplan, of the remaining areas of the project to be built.This community participation could be part of a more sustainable practise had residents been contacted during the initial masterplanning stage. As residents of a built environment, their opinions, local knowledge, and experience have intrinsic value and could have saved money, energy, and emissions for HafenCity.

Taking a wider look at emancipatory practises present (or absent) in HafenCity, it should be noted that while residents are encouraged to form a sense of community, in some cases even financially incentivized to do so, this is still a top-down approach. Community participation ensures that power is genuinely in the hands of the people, with their requests and priorities heard and inciting progress, or certain actions, or events. It is not community participation in the true, ecocity sense, to move into a household, and be given an edifying ‘information kit’ that explains how to function in the neighbourhood, in order to neatly slot into the machine of HafenCity.

The careful public design and way of life prescribed in HafenCity has, among others, a particular repercussion regarding the balance of residents’ public and private lives – with HafenCity’s increasingly public life- style, residents are losing out on valuable privacy and time to themselves. So an imbalance has been created due to the insistence of the top-down approach dictating precisely how bottom-up inclusivity should work. HafenCity resembles a ‘brand community’, and this brand seems particularly imposed on as opposed to adopted by residents.

So, the question arises, who is this city for? The racial makeup of the city is an extension of Hamburg’s – more than half of the city German residents, approximately 25% of inhabitants are of a migrant background, and less than 15% are non-German residents. Dubbed by many as the ‘rich people’s ghetto’, it seems as though the demographic seems to be just as homogenous in class, regardless of how HafenCity advertises its affordability and potential for diversity.

HafenCity seems to benefit its development company most – and why shouldn’t it? HafenCity Hamburg GmbH put a lot of effort and investment into engineering this ‘comprehensive framework’ to ensure its profitability and success.

Betim

City type Existing build

Community Participation Present

A slum in Betim, Brazil in need of basic amenities (energy, clean water, and waste management) from the government for 2 decades was able, through local community, to organize and obtain those benefits it was otherwise obtaining illegally, compounding on the reductions of its quality of life.

In the city’s system of multiple actors and multiple scales, citizens as actors and stakeholders usually have their needs and visions overlooked. Such an approach will integrate both bottom-up as well as top-down approaches.

The community took on a citizen-led integrated, approach.[20] This entailed a community representative, chosen by the people to speak for their troubles, their rights and needs for basic amenities, and to be able to initiate ‘democratic dialog and meetings’.This single representative of Betim’s neighbourhood grew into an entire representational commission – successfully representing the citizen as a stakeholder – which then approached local government, seeking solutions.

The representatives, despite obstacles, discontinuals, and dismissals with bureaucracy, were able to establish the clear goals of the neighbourhood, and understand the non-negotiables of the government. Once a law amendment allowed the land of the slum to be recognised as part of the city. This removed the onus of paying for land ownership to gain access to basic amenities, off the shoulders of the residents, who were unable to pay. This highlights a shortcoming of community participation requires certain resources – which may differ from region to region – to work. It may be a minimum amount of monetary backing in some cases, but in all instances of community participation, it requires a need and will of the community to take the power into its own hands and create the change it wants to see.

Once the land was legally recognised, the local energy provider agreed to the commission’s requests and moved forward to provide safe and reliably connected electricity, since both parties did not want illegal connections, and both parties did not want a waste of energy resources.

Betim is a case study in the positive ‘spillover’ effect that occurs not only from neighbourhood to neighbourhood with physical resources, but also access to positive impact policies and non-physical resources. In a single slum pursuing SDG1 for basic amenities, the commission was able to ensure the achievement of justice and building strong institutions (through lobbying for a better legal framework for the neighbourhood), ie., SDG16. Upon the households in the neighbourhood acquiring legal connections to the national grid, SDG7 was achieved. In the way of radical increments and just transition, the commission then opened up the floor for negotiations with the sanitation company to obtain clean water, the acquisition of which checked boxes on SDG6. Further work done for good roads, public transport, development of public policy, and low energy promotion means SDG17 is underway. As the neighbourhood obtained each SDG, the reputation of the neighbourhood spread through Betim, and interest and activism in the community commission caught on, with more citizens gathering interest in and voicing their opinions and experiences. The SDGs began to be earned not only by a single neighbourhood in Betim, but by the entire city, especially as SDG17 brought on the construction of schools, children’s centers, a reference center, and a low-cost solar heater program for households.

This is the citizen power of partnership: citizens are empowered to negotiate trade-offs with the traditional schemes of authority.

The reference center, since establishment, has been a point of communication locally and nationally – with municipal offices, schools, groups of residents, and as a springboard for project proposals. It has arranged for events such as university debates, resource reuse projects, as well as seminars and workshops for education and training of people and employees.

Betim has since burgeoned, from one neighbourhood achieving multiple SDGs, to the whole city coming to the forefront of the nation and becoming a Model City in the Community in ICLEI, with links to other sustainable cities within and outside of Brazil.

From its beginnings of a slum requesting basic amenities from the local government, to a city representing New Renewables and sustainability progress at international conferences, Betim’s future goals are aimed at reducing GHG emissions in the city through policywork, and establishing programs for architects and engineers to integrate solar thermal panels in designs and projects.

The community participation exhibited in Betim fully aligns with the people-centered, citizen-led approach – the power was taken into citizens’ hands, ensuring their voices were heard, and visions for the city’s potential fulfilled.The various SDGs achieved in Betim have allowed for an increase in employment, real estate booms, and infrastructure projects – among other positive impacts. Betim is seeing the fruit of a community’s honest labor towards the securing of basic rights from the government, with economic success, sustainable ventures, and increased quality of living for its people.

Evaluations on Case Studies

Creating an evaluative indicator for the sustainability of the case studies would require, among the many evaluative indicators already researched and established in the field, a selection of different criteria that would assess the cities across the different social, economic, and environmental sectors, in line with the working definition of sustainability provided earlier in the report. The indicator chosen is the Indicator system for evaluating urban sustainability, as devised by Arbab in 2023.

As the ecocities in question are from different countries with different levels of development in economy, and part of different census programs, it has been difficult to match up the indicators for a fair evaluation. Some modifications, therefore, will be made.

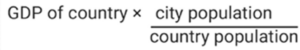

For example, while Betim, Brazil has extensive GDP information dating back many years, HafenCity and Masdar do not.Therefore, an estimated average has been calculated, by getting growth of GDP percentage per capita, and then multiplying by the population of the city, as follows:

In case the population of the city in a particular year (the year chosen is 2018 as it has the most overlap of census data) is unavailable, a ratio will be taken of the city against a related region in a year where the pop- ulation information is available, and the data will then be extrapolated to that year. For example, HafenCity’s population in 2018 is currently unavailable, however, it is available in 2022.Therefore, a ratio will be drawn up of HafenCity’s population to Hamburg’s population in 2022, and extrapolated to the year 2018, as Ham- burg’s population is known in 2018 as well.This will provide an estimate of HafenCity’s population in 2018, and the above formula will be applied to find HafenCity’s GDP – except ‘country’ will be replaced by Hamburg.

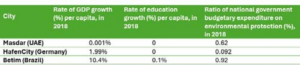

The indicators are as follows:

- growth rate of GDP per capita in the city, (indicator of economical success)

- rate of increase in education in the city, (indicator of societal success) and,

- ratio of government budgetary expenditure on environmental protection (indicator of environ- mental success/awareness).

The reason why GDP growth rate is chosen as an indicator, as opposed to GDP per capita, recalls the fact that these cities are in countries of differently developed economies. An effective sustainability system will positively impact the economy – but the base level of economies will be different for each city. A growth rate, however, depends more on the quality of the impact itself, than the quantitative input of economic data across the years.The rate of increase in education has been chosen similarly, since Masdar and HafenCity are both new-build cities attracting particular demographics, whereas Betim is a pre-existing city amid tran- sition.To be able to show the actual impact that achieving SDGs has had on each community, a more quali- tative route should be taken, hence the rate of increase in education being chosen as an indicator. The ratio of budgetary expenditure also seems to be a qualitative indicator – the higher a government prioritises the environment, the more effort it is putting into its ecocity, and the more it is willing to spend on it.

The indicative table and discussion of results can be seen below.

Based on the indicator results shown above, Betim has come out between the three ecocities as the most sustainable. This can be seen through its highest rate of increase in GDP, given the boost that its multiple sustainable and equitable endeavors are giving to the quality of people’s living conditions, and therefore their productivity in their different professions, which is showing clearly in the economic productivity of the city.

The rate of growth of education amongst citizens of ecocities is a more nuanced topic, but one that shows Betim’s dedication to progress nonetheless.The complexity here lies in the fact that Masdar and HafenCity are both new builds, with more resources than residents at this point in time. The demographics both of these cities appeal to, as discussed beforehand, are another aspect of this quantitative result: all residents moving into Masdar or HafenCity arrive already able to afford the lifestyle, the residential units, and the education. Everyone moving into these cities is expected to be educating their children, and so there is no growth, as it is always at a steady 100% – or extremely close.This is why, although there are currently no census data on this aspect of city life for either Masdar or HafenCity, the assumption has been made. It follows that, since the education rate is this steady, there will be no ‘growth’. Betim, on the other hand, is a pre-existing built environment in the Global South, where there is considerable growth potential. In Betim – and Brazil in general – there is an IDEB (Index of Development of Basic Education),21 and the rate of education growth for this indicator was calculated by simply calculating the rate of change of the IDEB between 2017, and the year 2018, to show the growth in 2018.

The ratio of national government budgetary expenditure on environmental protection is a more generous estimate for each city than may have taken place in real life, in 2018 – the budgets of Ministry of Environments were simply divided by the total government budgets in 2018, and no more. Since each country has a different number of cities and different number of environmental protection prerogatives, and no census data was found on this particular facet of the indicator for these cities, the values present above are estimates of the ratios spent on each ecocity.

Across all 3 indicators, Betim, the pre-existing city, the city of community participation, where the voice of the people was heard and honored and justice was, eventually, given where due. These results and circum- stances point towards the inherent sustainability of community participation with bottom-up approaches to justice, rights, and policymaking, as well as the inherent sustainability of the transitioning city, as opposed to the prescriptive, top-down strategies of new build.

The shortcomings of community participation have been, as previously discussed, to be, firstly, lack of, or waning incentive, and, secondly, lack of funding to be able to achieve community goals.

To ensure that community participation can begin at any time in either a process or period of stagnation in a city’s development, these two challenges must be overcome within the policymaking of the city.

Whether new build or transitioning, the city must set up a machination for communities to have the power to set up their representatives, representative commissions, and so forth, as they see fit.

Additionally, each national government, local government, and/or municipal authority, should have a state-mandated budget dedicated to community participation commissions, for lobbying, campaigning, grass- roots initiatives, and other political action. This budget should not only be accessible to the communities, but also able to be donated to and partially invested in government works to allow the community a means of revenue, further broadening their opportunities as a collective.

Finally, educational outreach programs should be spread across nations regularly, for communities to be able to learn about different programs, actions, and ideas that they initiate and incubate locally, adapting information and strategies to their own specific contexts.

Through the new build case studies that hold the absence of community participation, the failure of cities can be seen: the continuation of the mirage, the widening of the green gap, under the guise of sustainability – when such practises do not in fact seek the propagation of sustainability.

The case study of transitioning Betim, also, investigated through its narratives and evaluated through numer- ical data, has shown the positive impact that the presence of community participation leaves on an ecocity: a genuine venture towards sustainability.

The flaws and biases of today’s capitalistic systems need to be faced with honesty, and not only demanded to change but made to change, radically, incrementally, and for the public, through establishing better, more just, legal frameworks – and that, at its best, is what community participation is capable of.The market-driv- en logic that has pervaded today’s society so far as to create green mirages for the more privileged to enter, while the marginalized peoples of today and tomorrow go unheard and unseen – must be overturned.

Each pre-existing city has its own cultures, its own local knowledges and wisdoms. If each city had its own Betim story, contextualized to its own history and its own people, the justice served to each city’s people, and their empowerment and progress, would mean an incredibly bright future of the world, for people, for economies, and for the environment.

Where power has come to be shared it was taken by the citizens, not given by the city.

– Arnstein

Further points I need to look into after this are the different models and interpretations that ‘community participation’ itself can take. This is definitively a biased post since I’m all for participation, but I need to better understand the limitations of participation – there are, after all, going to be concerns and issues that local community cannot definitively solve. Then there is the adverse side of community – how it can breed exclusion and power. Where and what is the balance between inclusion and exclusion? This would be interesting to look at, maybe through the lens of the course Exclusion and Inequality. I’ll be looking at the further readings of that course and maybe come to some sort of better understanding from there.