‘Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things’ by Jane Bennett was a significantly hard read for me. The various concepts of ontology and materialism elaborated through multiple standpoints while engaging, were also difficult to wrap my head around. Her narrative is imaginative and the writing oscillates between the tangible and the nontangible, scientific and philosophical. The reading muddled my thoughts and made me think about a few themes I previously had not paid much attention to. This blog is a humble attempt to put across the same muddled thoughts and questions, while still trying to concretize them in my head.

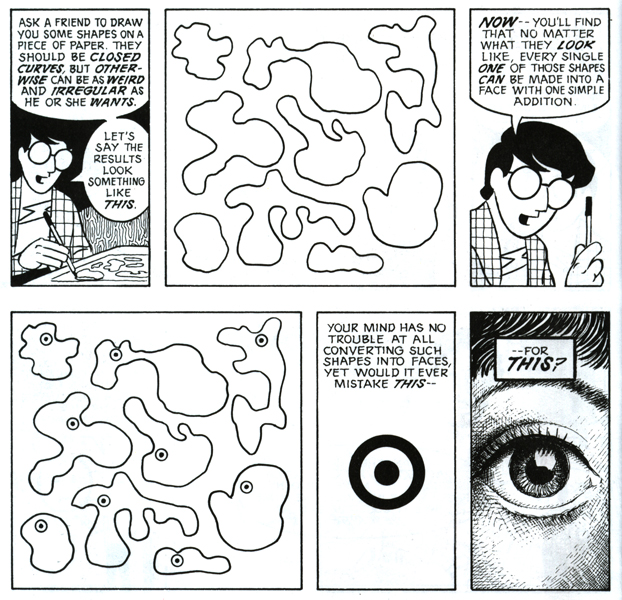

One of the concepts discussed in the book particularly held my attention – Anthropomorphism. “Anthropomorphizing means attributing human qualities to non-human things — such as objects, animals, or phenomena. Some people do this more than others.” (Barkley, “Why Do We Anthropomorphize?”). By attributing emotions to non-human entities, Anthropomorphizing supposedly elicits empathy and a feeling of connectedness. I correlate this notion immediately to my Indian culture, where we tend to humanize or even worship certain inanimate objects. For example, it is considered fundamentally wrong to touch paper with our feet, an offense to the Goddess of learning and wisdom, Saraswati, since paper or books are perceived as tools of knowledge. The cultural conditioning of the same is so solid that even people who are far removed from religion as a concept tend to feel distinctly uncomfortable with the thought.

On a bigger more general note, does this make us respect the materialism of the object that we treat it more judiciously? Does ascribing humanlike tendencies to “agents” elicit ethical care and consideration from us? Does anthropomorphizing also indirectly imply that “agency” lies with us, humans? Jane Bennett in an interview states that – “Anthropomorphizing can be a valuable technique for building an ecological sensibility in oneself, but of course, it is insufficient for the task as analogies are slippery and often misleading because they can highlight (what turns out to be) insignificant or non-salient-to-the-task-at-hand resemblances.” While I mostly agree with this, it also makes me wonder about the metaphorical line between significant and insignificant resemblances. Who is to decide what is significant or insignificant? Shouldn’t any form of respectability or empathy for “things” be a way forward?

As an Interior designer, my stance on how the concept of Anthropomorphism contributes to the domain is still a work in progress as human perception of design and the emotions it elicits is layered. Many different factors like the materials used, textures, forms, colours can incite different emotions in different individuals, which is why, as mentioned before, I believe perception could be layered. However, my recently developed understanding of this concept makes me want to delve deeper into this perception and evaluate how to further develop these implications.

Bibliography –

Barkley, Sarah. “Why Do We Anthropomorphize?” Psych Central, September 14, 2022. Available at – https://psychcentral.com/health/why-do-we-anthropomorphize.

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant Matter: a Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.