Let’s talk about death.

This was the tagline for an exhibition at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, provocatively titled Death: The Human Experience.

Opening in late 2015, this exhibition was put together with an agenda; to aid in the de-stigmatization of conversations about death, dying and the dead. This blog analyses the importance of the exhibition and connects it to wider issues around collection and display of human remains which were also relevant to our GRP project.

Header from the exhibition website asking some of the questions the physical exhibition tackles. It bears the exhibition’s unofficial tagline, “Let’s talk about death.” (Screencap from https://exhibitions.bristolmuseums.org.uk/death/)

Museums and Death

Archaeologists, museum practitioners, claimants and especially the public often disagree over the subject of human remains and museum exhibitions regarding death (see Walker, 2000). An exhibition curator beginning a conversation around death involving depictions of the dead and displays of human remains, must navigate issues around consent, representation and legality.

The ethical dilemma surrounding display of human remains and depictions of the dead in museums is relatively recent and has its origins in concerns around the collection of Indigenous bodies. These conversations gained momentum during the civil rights movements of the 1960s. Indigenous concerns over the treatment of their ancestors have their roots in the Colonial period, when Indigenous human remains were systematically collected because of their importance in helping to give evidence to evolutionary theories popular at the time. Most were obtained opportunistically and without consent. (Fforde et al, 2004).

Fforde (Hubert and Fford, 2002) places the collection and display of indigenous human remains into an historical context by stating that:

[I]ndigenous human remains were widely procured during the colonial era for scientific research conducted within the race paradigm. Research was undertaken by phrenologists, comparative anatomists and, later, physical anthropologists, by those advocating monogenism, polygenism and Darwinian evolutionary theory.

The responsible museum curator should consider the provenance of any human remains they choose to display and understand the ethical concerns that these histories raise.

In response to human tissue act of 2004 (Price 2005) which introduced new restrictions on ways in which human remains could be collected in the UK, Many museums have sought to change their practices in regards to remains collections. Prior to this legislation, the Australian and British Prime Ministers issued a joint declaration to increase efforts in repatriating human remains to Australian Indigenous communities (Butler, 2001). Although, some UK museums had repatriated human remains previously, efforts to repatriate human remains from prominent museums such as the British Museum and the Natural History Museum had repeatedly failed as the British Museum Act (1963) legally prohibited the de-accessioning of any items from their collections (Weeks and Bott 2003).

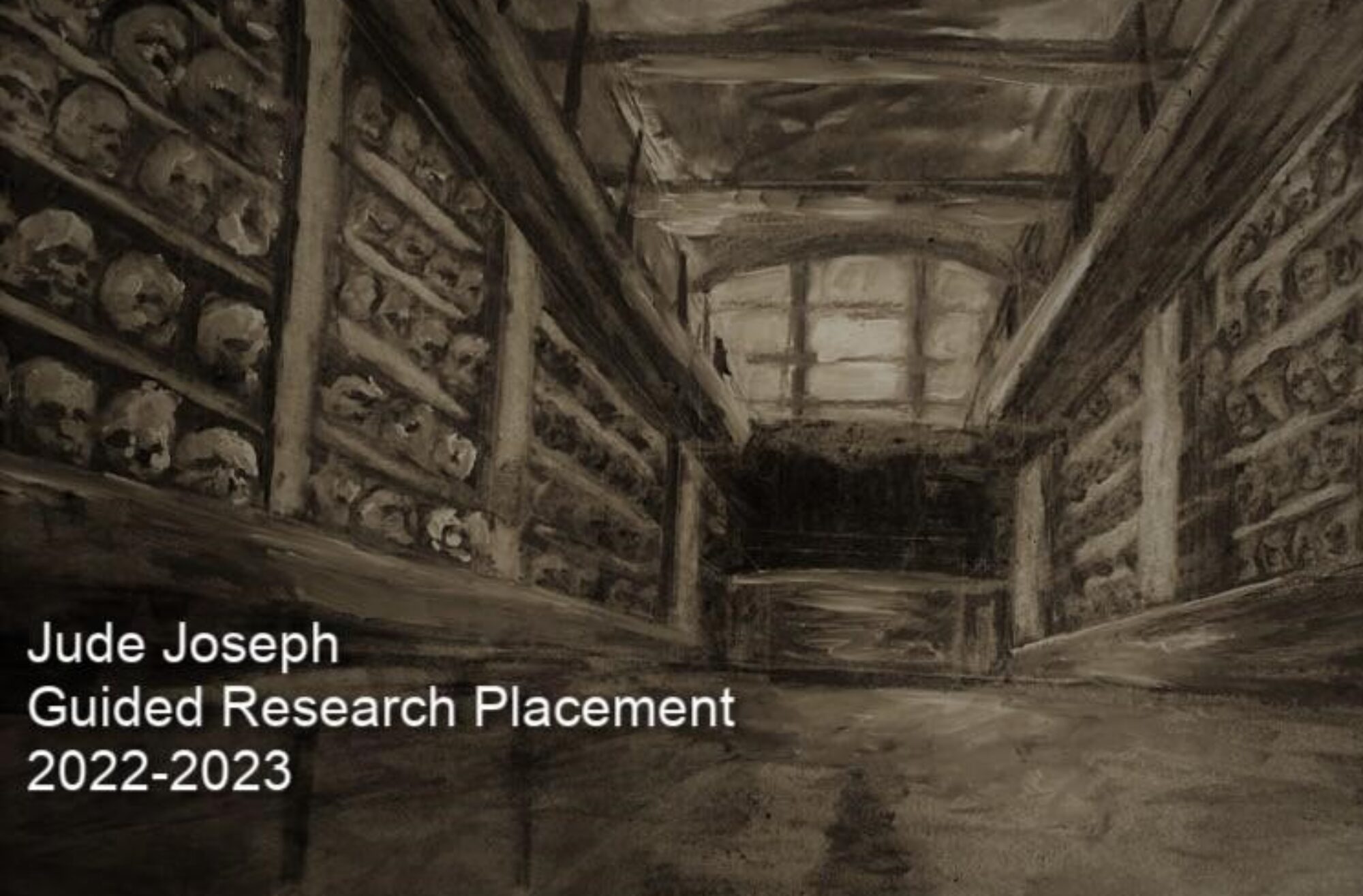

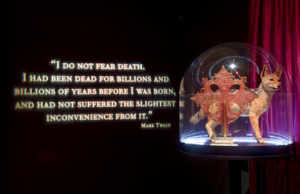

Both Death: the Human Experience, as well as our GRP event, Face to Face, a Dialogue on the University of Edinburgh’s Skull Collection, take place amongst these changing attitudes towards display of the dead in museums and considerations around provenance of remains. Where their responses differ in regards to display is that the curators of Death: the Human Experience chose not to show any actual human remains, instead opting to exhibit replicas and reproductions (which involves another conversation around the ethics of reproduction, see Campanacho and Cardoso, 2019). Our event will seek to directly consider the provenance and historical circumstances by which the Skull Collection came to exist, making consideration around showing real human bones necessary. The Bristol exhibition’s approach is broader and instead investigates cultural attitudes towards death as a concept. The design of the exhibits are more sensational with lights and sound also being used to creative effect in order to better capture the visitor’s imagination. In addition, the Bristol exhibition involves display of taxidermy; government guidance introduced in 2004 prohibits the collection and display of human remains alongside the remains of animal specimens. This is done for the purpose of respectful treatment and cultural sensitivity (Rae 1996). For these reasons, no remains are present in the exhibition.

(Screencaps from https://www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/bristol-museum-and-art-gallery/whats-on/death-human-experience/)

Exhibition Content

This exhibition was held in a gallery environment split between multiple areas, each dealing with a different facet in the conversation around dying. Every part of the space contained a variety of media including physical objects, sound, video and creative lighting, often to the effect of creating an atmosphere to engage the audience more fully.

The Symbols of Death section contained many depictions and objects associated with death from a variety of cultures. (Image from https://advisor.museumsandheritage.com/features/death-is-it-your-right-to-choose-new-installation-at-bristol-museum-art-gallery-explores-taboo-subject/)

The exhibition exists in an open plan format with audience members being allowed to freely engage with displays on funerary rites, mourning practices and burials. Also in this area were screens displaying interviews with professionals in the fields of assisted dying and palliative medicine offering views on how changing attitudes and government legislation could improve end of life care. This space also hosted two panel debates on the ethics of euthanasia.

Finally, before the exit there was the reflection space. A quiet area where visitors could reflect on their visit and record any thoughts in a visitor’s book. This was critical in order to offer an environment for decompression after a potentially emotionally difficult exhibition.

(Image from death: the human experience | Bristol Museum & Art Gallery (bristolmuseums.org.uk)

Video from Death Professionals in Conversation – YouTube)

Reception and Impact

This exhibition was massively popular with the highest number of visitors recorded to an exhibit at the museum and each debate panel quickly selling out, proving that in the UK there is a strong appetite for conversations about death. The importance of these conversations is evident in healthcare, as clinical lecturer KE Sleeman (2013) writes “Poor communication at the end of life can cause deep distress, both for the patient and their loved ones, and may adversely impact on post-bereavement outcomes.” Sleeman notes that in medical teaching, courses on death and dying have only recently become a part of the curriculum and that many doctors enter the medical profession without being properly prepared to deliver end of life treatment.

Talking about dying with patients is hard, particularly

when there has been a long relationship with the patient

and the goals of care have changed. But honest

conversations, sensitively navigated, will strengthen

rather than damage the relationship between doctors

and dying patients, allow patients to prioritize and

prepare for the future, and reduce suffering in

bereavement for those left behind.

(Sleeman, 2013, p198)

Conclusion and Further Thoughts

To consider a museum as a space for conversation, we can also see them as a tool to speak about difficult or stigmatized topics. I think that my colleagues and I working with the Skull Collection are in a unique position to open these discussions, especially on how the body is treated after death.

References

Butler, T. (2001) ‘Government announces details of working group on human remains’. Museums Journal 6, 5

Campanacho, V. and Cardoso, F.A., 2019, March. Surveying Portugal residents’ view on the creation and dissemination of three-dimensional replicas of human skeletal remains. In 88th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists.

Fforde C, Hubert J, Turnbull P, editors. The dead and their possessions: repatriation in principle, policy and practice. Psychology Press; 2004.

Hubert, Jane, and Cressida Fforde. “The reburial issue in the twenty-first century.” Heritage, Museums, and Galleries (2002): 116-32.

Price, D., 2005. The human tissue act 2004. Mod. L. Rev., 68, p.798.

Rae, A., 1996. Dry human and animal remains—their treatment at the British Museum. In Human mummies: a global survey of their status and the techniques of conservation (pp. 33-38). Springer Vienna.

Sleeman, K.E., 2013. End-of-life communication: let’s talk about death. JR Coll Physicians Edinb, 43(3), pp.197-9.

Walker, P.L., 2000. Bioarchaeological ethics: a historical perspective on the value of human remains. Biological anthropology of the human skeleton, 3, p.40.

Weeks, J. and Bott, V. (2003) Scoping Survey of Historic Human Remains in English Museums undertaken on behalf of the Ministerial Working Group on Human Remains. London: DCMS [Original source: https://studycrumb.com/alphabetizer]