1: Putting it all together.

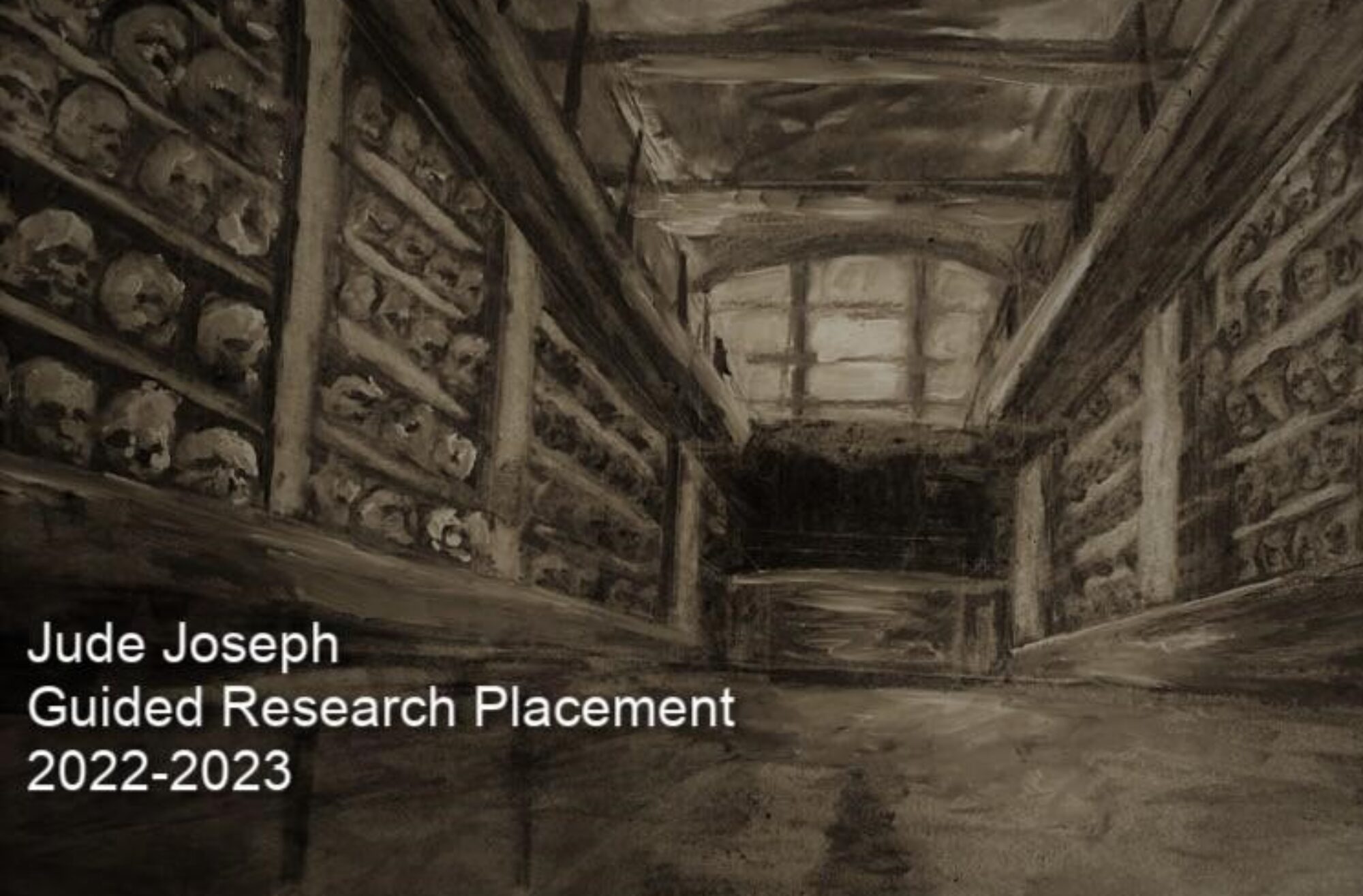

When Hallie, Fiona and I were put in a group after electing to work on a project centred around the Skull Room, there was a sense of trepidation. As the three of us learned about the history of the skull collection, and were eventually given a tour by the curator of the Anatomical Museum, Malcom MacCallum, it was impressed upon us the emotional weight, even darkness that this space carried. We were informed that the skull collection came to exist as a means to evidence racist science from centuries past. We learned how each skull was added to the collection, through circumstances that could be described as unethical at best and prejudiced, violent and dehumanising at worst. We were encouraged by our supervisors to think of these skulls, not as artefacts or relics, but as the remains of human beings. This is where our thinking around creating a project that would lend some humanity back to the people housed within this collection began.

No photos of the skull room itself are permitted. This measure exists as a way to show respect for the dead who are kept there.

With this in mind we knew that a traditional, curated museum display would be difficult to put together. For one, we felt it would be entirely inappropriate to display these skulls to anyone outside those who worked within the department directly. Instead, what we felt was needed was a dialogue around how this collection could be improved.

There are many controversial elements to this collection, one example being that the skulls are still kept together with their traditional labels, displaying outdated and at times racist descriptors beneath the heads of the dead individuals themselves. Because these skulls are hidden away in the basement of the medical department, no one bar the curators of the anatomical museum have a say in how it should exist. We wanted our event to change that by opening up the conversation to a wider audience.

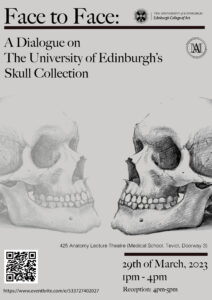

After deciding that we wanted to create an event, our first question was should this take place in person or online. We eventually agreed that an in person event would be most appropriate. At first we were referring to this event as a symposium, however Fiona suggested that the term dialogue would be more appropriate as it connoted a more equal dynamic between those conversing. With this in mind, we developed a title:

Face to Face: a Dialogue on the University of Edinburgh’s Skull Collection.

Poster for the event designed by myself. Our promotional material went through a number of iterations, with each improving on the event’s visual identity and incorporating venue, time and even date changes. The event originally slated to take place on the 15th of March had to be moved to the 29th following the announcement of a staff strike. This change required a lot of last minute reshuffling.

2: Handling the skulls

As part of the brief, we were tasked with learning more about how metadata gaps can occur within small museums. We were also offered the chance to gain some object handling skills which would be useful for conservation and archive work after university. In order to get some direct experience with these, we were allowed into the anatomical museum to conduct cleaning and photography of some of the South American skulls from the skull room, as well as being set the task of entering information about each skull into the anatomical museum’s digital archives.

None of the members of our group had ever handled a human skull before! The fact that we were now holding something which had once been part of another human being’s anatomy was a powerful feeling, and it meant that each of us handled the bones with extreme care and respect. Ruth Pollitt, one of the curators of the museum, informed us how damage can occur when items from the collection are improperly handled and how these mistakes can be avoided by following strict guidelines of care. Fortunately for us beginners , we were also informed that human bone was rather robust, meaning that we would be allowed to clean these objects given our lack of experience.

We were given access to equipment regularly used within museums to remove dust and dirt from displays. We used small vacuum cleaners to remove dirt, caked into the bones. Likely still remaining from the soil they were taken from.

Image from https://www.preservationequipment.com/Catalogue/Cleaning-Products/Vacuum-Cleaners

The next step after cleaning had taken place was to photograph and document details about each skull. We were directed by Ruth about the proper way to do this as well as details to note on the skulls: potential marks left by instruments for taking phrenological readings, text etched into the bone by the original collectors, and signs of binding practices which were used to change the shape of the skull. When each of these were found, this information was added to an excel database alongside the photographs we took.

In attempt to find more information about the provenance history of each of these South American remains, we were given access to records kept by the Edinburgh phrenological society during the 19th and early 20th century. This information was useful in spotting any changes that had occurred since the skulls were first collected, such as faded labels or damage caused by handling. What these records made us painfully aware of however was how little respect those who collected these skulls originally showed to the communities from which they plundered. There were countless misnomers referring to important religious sites from which the bones were taken, derogatory language used to refer to specific ethnic groups and large gaps in information about who the people were or what they believed. For this reason, some of the gaps in our knowledge about these skulls are very unlikely to ever be recovered.

Nevertheless, the details were able to find included physical details about each skull and any distinctive features that may have given clues about the living individuals. All of this was recorded and will hopefully be of use to future researchers.

3: Selecting Our Speakers

Left to right: Zaki-el-Salahi, Nicole Anderson, Debora Kayembe, Tobias Houlton.

Part of our brief for this project asked us to tell the story of the skull collection while engaging with decolonial thought and considering the perspectives of those involved in the conversation. Because the skull room, from a decolonial framework, exists as a marker of outdated attitudes and museum practices that disproportionately affected marginalised communities, including indigenous peoples and people of colour, we knew that our perspective alone would not be enough to tell the story of this collection.

We began by searching for experts who would have a cultural connection to, and research interest, in the skulls in the collection:

The first on our list was Zaki-el-Salahi, a member of the Edinburgh Sudanese community and an anti-racist activist who had a background in repatriation work. Zaki’s and his community’s direct link to specific Sudanese skulls housed in the skull room made this a deeply personal effort for him and his enthusiasm and drive towards the goal of commitment to change regarding the skull room made him a very valuable asset to the project.

The next speaker we secured for the event was Dr Tobias Houlton from the University of Dundee’s facial reconstruction and medical art department. Dr Houlton’s role within the dialogue was to describe the ways in which a face could accurately and respectfully be applied to the remains of the deceased. A powerful tool in the campaign for humanisation.

The third was Nicole Anderson, a PHD student focusing on the histories of Canadian first peoples. She was able to offer a perspective on the importance of decolonial work and how indigenous people have been historically affected by the practices which led to the creation of the skull room.

The final speaker was Marenka-Thompson-Odlum, a part of the labelling matters project at the Pitt-Rivers museum in England. She was able to speak about museological practices and how the way that exhibitions are labelled can have a huge effect on how we interpret history.

In addition, we asked the Rector of the University, Debora Kayembe to make a few closing remarks at the end of the event. Her speech was incredibly powerful. She connected the event to her prior humanitarian work lending the event a broader context. Her commitment to decolonising the collection was an inspiring note to end the event on.

The Rector’s Closing Remarks.

4: Some Obstacles

My first challenge was that I was new to collaborative work at a University level. Adjusting this meant that I had to quickly grasp a lot of methods of working that were new to me!

It took me a long time to grasp the complexities of Google Docs, however when we got into a rhythm of uploading meeting minutes, agendas and speaker communication packs, it became indispensable.

I often found it difficult to keep track of the various threads we needed to follow to ensure that the event ran according to plan. These included simultaneous communication with a variety of different speakers, managing numbers of attendees and ensuring that we didn’t include too many for our capacity and navigating relationships during what was a very challenging and emotional project. Thankfully the two other members of my team were very pro-active and were able to support me when I needed help. Admittedly, the three of us often had disagreements on the way that the the project should be organised, however through moderation given by our supervisor Kirsten Lloyd as well as PHD student Lizzie Swarbuck, things got back on track and we became a much more cohesive unit during the second semester.

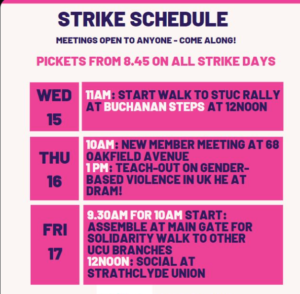

Another spanner in the works came in the form of an unexpected strike by the UCU, meaning that to hold the event on the planned day would constitute crossing a picket line, something which none of our group was comfortable doing. We held an emergency meeting after the strike was announced and decided to move the event forward to the 29th of March. Unfortunately, this meant that all of our promotional material, as well as speaker information packs had to be changed to accommodate the new date. Thanks to Google Drive however, we had a well organised archive of our assets meaning that the work needed to make this change was not too laborious.

The UCU strike schedule which was announced for the day of the Event and a section from one of our original posters, displaying the originally planned date.

5: Event Day

It was so rewarding to see the fruits of our labour after many months of hard work. As the audience filtered in, we got a real sense that this dialogue was about to be opened up to the broader public for the first time.

We decided to host our event in the old anatomy lecture theatre in the medical school. We felt that this would be an appropriate location for the event given the skull room’s connection to Anatomical teaching at Edinburgh University.

Our group did technical runs before the day itself to ensure that microphones and recording equipment were working properly. Before the event began we made sure each speakers slideshow was properly in place and set appropriate audio and light levels.

Between each talk, our moderators Gaia and Maryam opened the floor up to questions. Those in the audience could also submit specific questions to our speakers through an online forum on Slido.

At the halfway point, an interval was called. During this break, the audience was given a tour of the anatomical museum by curator Malcolm MacCallum. Myself and Fiona child also gave talks within the the anatomical museum, focused on providing information about the displays that was otherwise not shared with visitors.

At this point in the day, Hallie also conducted her “Museum of Me” creative workshop, during which participants were asked to imagine how they might wish to be displayed in a museum. This part of the day was important to provide emotional respite as well as to foster empathy between attendees and those in the skull collection.

Zaki gives a powerful speech about the work of the Edinburgh Sudanese Community.

At the end of the afternoon, refreshments were provided and there was an opportunity for attendees to reflect and network. There were also a number of journalists in attendance who took this opportunity to speak with us about what they had experienced on the day.

The event was a success and we went away with the feeling that we had created something unique and memorable for those who came. Malcolm was also happy with how the day went telling us that he was pleased to have been involved with a dialogue which could help kickstart further decolonial action within the anatomical museum.

6: Feedback and Conclusion

For this project we were tasked with responding to a brief which asked two questions:

- How might we tell the complex stories of the Skull Collection from a museological perspective while engaging seriously with decolonial thought and struggle?

- What strategies can be employed to address knowledge and metadata gaps in small museums?

Our group responded the the first by retelling the complex story of the skull collection through the framework of humanisation and dialogue between individuals. The event we held shared the history of the collection beyond the university; something which had not been done previously. In doing so it was handled with sensitivity and care.

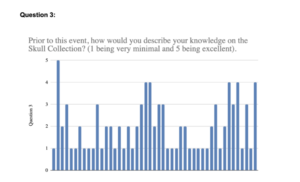

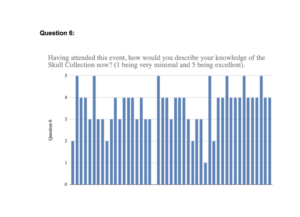

At the conclusion of the event, we asked participants to fill in a survey which gauged their responses.

These graphs showed a huge increase in knowledge from audience members who previously knew very little about the collection.

We also asked audience members for constructive criticism regarding the event. Some suggested changing the creative workshop as it was slightly difficult to see how it related to the rest of the event. Poor audio within the lecture theatre was also an issue on the day. Many attendees were keen on increased funding being put towards maintaining the anatomical museum. Hopefully these results will be useful to the curators in the future.