The Skull Room, Phrenology and The Commodification of the Body.

Portrait of Samuel Morton, an American natural scientist, physician and writer. Morton had a significant influence on two fields of study: Craniology, which is a term that has now become synonymous with phrenology and also polygenism, both of which are now deemed to be outdated examples of racist ‘science’

Image obtained from (https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/phrenology/)

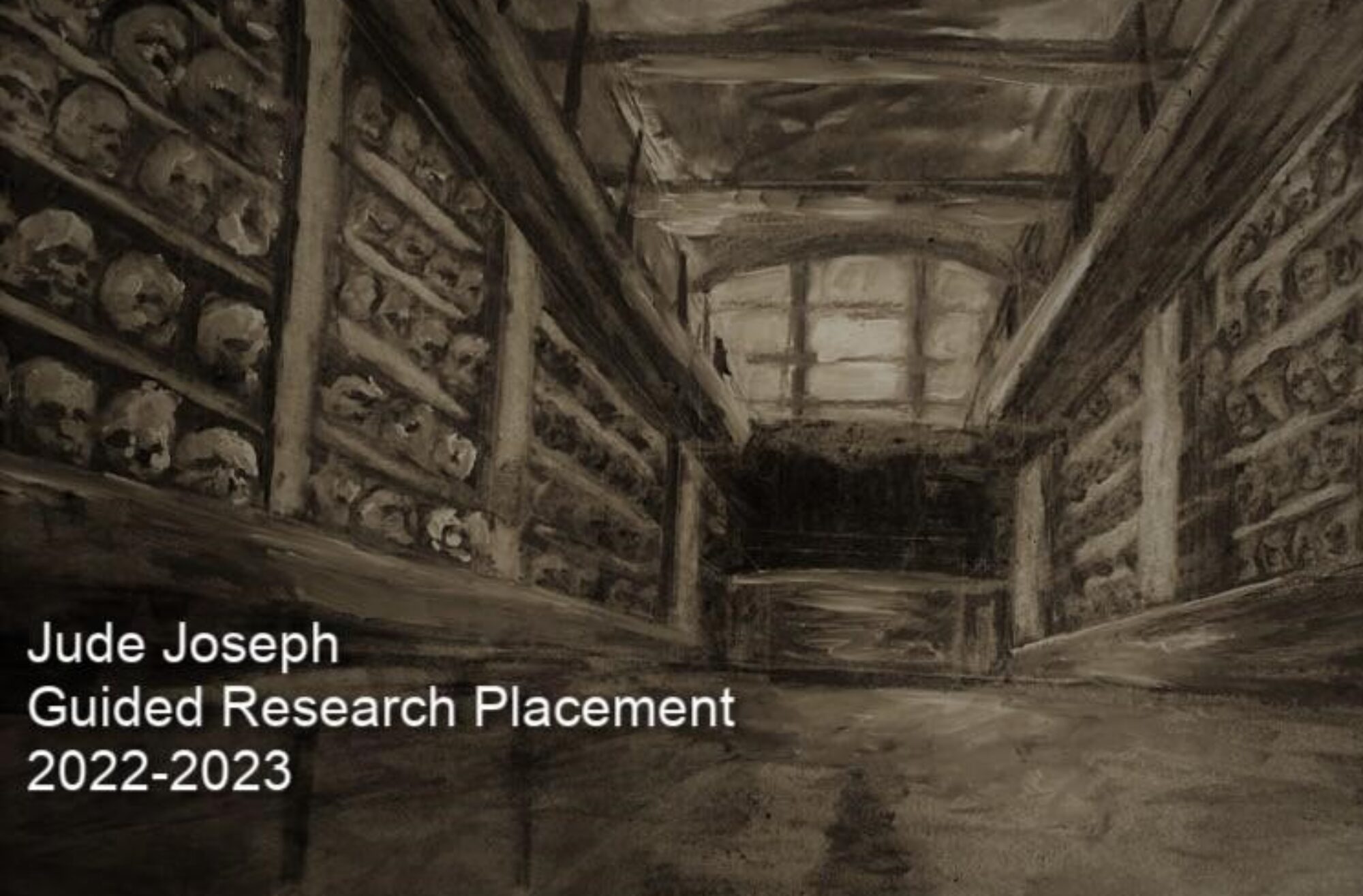

During my time working with the skull collection, I was struck by the extent to which the collection dehumanises and objectifies the remains of those who reside within it. During this placement, our supervisors stressed the importance of utilising humanising language when referring to the skull collection; instead of artefacts, objects or specimens, the skulls were to be referred to as ancestors, remains and even residents. This was stressed as a step to avoid the same commodification the skulls within the collection have historically been subjected to. This section analyses the extent of this commodification and in doing so goes into the history of phrenology, the outdated ‘science’ to which the skull room is inextricably linked.

To think of the human body as simply a commodity has deep implications regarding the value ascribed to human beings, and changing ideas about personhood that exist in society. Anthropology offers dynamic models of this kind of commodification which engages in the exchange of bodies both living and dead. In the estimation of the economist Mauss (1967), it is evident in anthropology that commodities exist not simply as raw materials or tools to achieve an end but also as being symbolically charged with links to social meaning, hierarchy and power structures. Any society which condones slavery also accepts that living people can be commodified and entered into an exchange market. When formulating a hierarchy of human value which could be used to justify the enslavement and de-humanisation of certain groups, many 19th century anthropologists looked for signs of inferiority and degeneration in the anatomical structures of indigenous cadavers. The increasing popularity of ideas posed by phrenologists in the mid-19th century, such as Samuel Morton, who wrote Crania Americana, in 1839, led to a hunt for proof of a racial hierarchy within the shape of skulls. In this fascinating book, Morton affirms the intellectual superiority of the “Caucasian race” over “Africans” and the “Native Americans” through analysis of physical characteristics and behaviours.

Phrenology, which claims a notional objectivity (Hamilton 2008) tries to connect behavioural patterns and intellectual capabilities with particular shapes of skull. The racial component of this outdated science required the comparison of the skulls of people born in widely varying geographical areas and an analysis of varying head shapes. To enact this practice, the Edinburgh Phrenological Society started gathering and organising skulls eventually amassing a collection of over 1800, still maintained today at the University of Edinburgh.

The organisation of this collection is remarkable in that the skulls are categorised by race (often unreliably so by their original collectors) and ordered in a set hierarchy, with skulls from Africa, South America and Asia being displayed in cabinets at the bottom level of the room and European and North American skulls in the shelving units above. In this way, the physical layout of the collection corresponds to theories propagated by Morton about racial hierarchy in terms of a capacity for intelligence. Constructed using scientific racism, These hierarchies would become a component of arguments supporting white dominance and eventually slavery. An example of this kind of argument comes from the doctor Charles Caldwell (1772-1853) who defended the practice of slavery using phrenology as a basis for his argument about Africans being inferior to Caucasians in terms of mental constitution (with evidence deriving only from the shape and size of skulls) (Poskett 2016). By using the remains of the dead as evidence in this way, a feedback loop is created between the objectification of the dead and the commodification of the living, whereby the dead bodies of the enslaved are employed as a means to justify the enslavement of living bodies.

The skulls of particular Indigenous populations were also considered a valuable prize by the phrenologist or skull collector; for example the skulls of aboriginal Tasmanians who were deemed invaluable as evidence of a supposedly less evolved form of human (Bennett 2004, 136–159). Other such examples include the skulls of Flathead Indians, a nickname originally created by Europeans to distinguish Native American tribes who intentionally altered the shape of their heads through binding practices. William Brooks was a member of the Bitterroot Salish tribe who was brought to Philadelphia as a human oddity whereupon in death, his skull became a great prize for skull collectors to marvel at (Parezo 2011). Indigenous skulls like Brook’s where not simply to serve as a means to evidence racist science, but as collectables and trophies of colonial conquest.

In conclusion, collections such as that housed within the skull room at the University of Edinburgh exist because of the historical commodification of human remains, whereby the remains were themselves used as evidence for ideas which attempted to justify further commodification. The project of re-humanising these remains is a step towards breaking this cycle of commodification. It is an attempt to view the skulls, not as a means to an end, but as an end in themselves. As the remains of human beings, not as tools to be used or curiosities to be looked at and displayed. Curation can play a part in this re-humanising process as it can frame these skulls in a new light and place them within a new context. Curators can even work towards the process of repatriation, whereby these skulls can be returned to the societies where they once lived as human beings.

References

Bennett, Tony. 2004. Pasts Beyond Memory. London: Routldege.

Hamilton, Cynthia S. 2008 . Am I Not a Man and a Brother? Phrenology and Anti-Slavery. Slavery & abolition 29.2: 173–187.

Mauss M. 1967. The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. New York: Norton

Parezo, Nancy J. 2011. “The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America’s Unburied Dead.” American Historical Review: 815–816.

Poskett, James. 2016. “Phrenology, Correspondence, and the Global Politics of Reform, 1815–1848.” The Historical journal 60.2: 409–442.