Repatriation and Display of Human Remains: The Legal and Ethical Considerations.

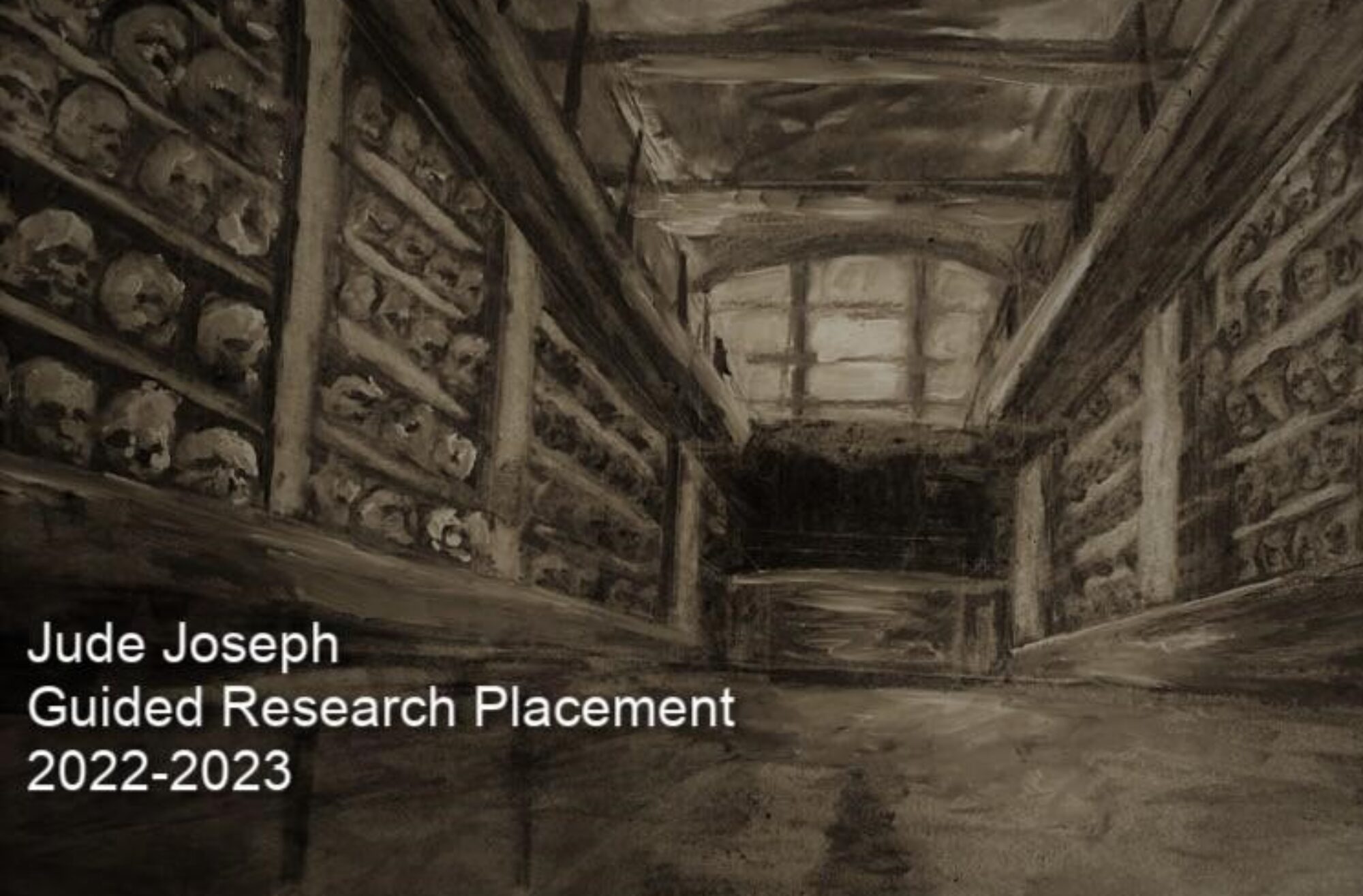

An illustration of the Skull Room by myself (March, 2023).

The Skull Room is central to debates surrounding repatriation, collection and display of human remains. This section analyses some of the issues that the existence of bodies as part of Museum collections raises, and offers a number of perspectives on the best way to approach this sensitive practice.

It is not uncommon to encounter a dead body in a museum. For example, Egyptian mummies remain to this day, a long standing staple of the museum-going experience in the United Kingdom. Until recently, these practices have taken place practically uncontroversially, however, in 2008 there was a great public outcry when the curators of the Manchester Museum decided to cover up the mummies in their Egyptian Gallery. While the museum stated that this was done in response to visitor feedback, a wave of criticism was nevertheless directed at the curators of the exhibit from members of the public who by most metrics were overwhelmingly in favour of the mummies’ continued display (Day, 2014). A wealth of media sources at the time reported on this story with the perspective that a long cherished and valuable exhibition was being removed by overly sensitive and out of touch museum curators, who had made this decision against the common interest of the regular person. Why then were the mummies removed from display?

Jasmine Day, writing in an anthropological journal which was in favour of retaining public mummy displays as a “tactile and engaging way for museum visitors to connect with the ancient past” (Day, 2014), suggested that this removal was part of an engagement with ethical concerns that originated in debates around repatriation of more recently deceased indigenous bodies from museums. She holds the perspective that museum curators are questioning why some remains, such as those of the indigenous dead, should have such a strong movement in favour of repatriation and removal from public display (Smith, 2004), while others, such as ancient Egyptian mummies, are exempt from such considerations. One possible answer to this question is the differing proximity to the present day and the stronger connection some modern visitors may have to indigenous ancestors on display as opposed to ancient Egyptian remains. A negative response could more likely be taken from encountering the remains of a person to whom one has a direct cultural connection.

In 2020 the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford removed its collection of Shuar Tsantsas (shrunken-heads) from public display. These unique exhibits, containing specimens originating from Ecuador, were taken down as part of a broader move to decolonise the museum. Museum director Laura van Broekhoven stated in an interview with BBC news that there was an effort to avoid visitors “misunderstanding other cultures as savage” (BBC 2020). Another source, Dr Errol Francis, writing for Culture& a prominent arts and heritage editorial in the United Kingdom, which had previously published a charter calling for museums to decolonise their collections, responded to the Pitt River’s reforms to its display:

I’m glad at last that these ghoulish displays of the colonial body as the dehumanised object of the western gaze is beginning to be addressed .

(From Batty, The Guardian, 2020)

Considering this change however, the Pitt Rivers Museum continues to display its collection of Egyptian mummies to this day. This indicates that ideas around who ought and who ought not to be displayed is subject to changing political climates as well as the age of the bodies in question, as opposed to a general displeasure with viewing the dead altogether. It remains true that even for museums seeking to decolonise and humanise the dead within collections, the complete removal of all human bodies from UK museums is a long way away, and for many museum goers, the display of human remains is still a worthwhile part of the experience.

There are specific legal requirements around the display and collection of human remains. In the government guidance for the care of human remains in museums (DCMS, 2005), extra consideration is given to remains as requiring special treatment from the rest of the museum collection. In a passage from section 2.6, the guidance states “museums with collections of human remains of significant size should create a dedicated storage area in order to provide the best possible conditions.” Though these regulations would have a large impact on smaller museums with more limited storage capacity in which to create a dedicated area for bodies (Morton, 2020), this change was still a step towards a more respectful method of storing human remains. Before these regulations were put in place, museums like the Natural History Museum in London tended to categorise human remains within the natural history section of their collections. This meant that human bodies were often stored alongside animal remains housed within the zoology collection. This government requirement that human bodies be separated from animal remains can be interpreted as an acknowledgement of the humanity of the individuals in the collection. This sectioning off of sensitive items also meant that museums could control who had access to handle these parts of the collection, allowing only those with specialised training to interact with bodies.

Despite this effort to ensure “respectful treatment,” what this means cannot be meaningfully defined. What is considered respectful in terms of the treatment and care of remains differs from culture to culture and depends on changing attitudes and sensitivities. For certain cultures, such as those of many indigenous peoples who resent that museums continue to hold ownership over the remains of dead ancestors, many of which were obtained through dubious means (Hanchant, 2002), there can be no such thing as “respectful treatment” while these remains are still part of museum property. While some museums may feel that they have taken steps to ensure that their conduct is respectful or dignified, those with a cultural connection to these remains may see things differently and repatriation may be the only solution. For example:

But then they don’t understand that from the Maori point of view, and this is where it goes back to a deep spiritual understanding, is for Maori that these are our ancestors not matter what. From 1769 when the first ancestor or 1770 when the first ancestor left, it doesn’t mean that we lost our connection to them; the connection to them is still here and it’s alive within us today. So, it may take over two-hundred years or three-hundred years for the ancestor to come home but we still want them home.

(Te Herikiekie Herewini, Te Papa Tongarewa, June 2015)

The nature of the collection of human remains means that this area will always be subject to strong opinions. In order for museum curators to practice human remains disciplines ethically, they should be aware of the variety of ethical concerns, as well as the legal guidelines intended to ensure respectful treatment of the dead.

References

Batty, David, “Off with the Heads: Pitt-Rivers Museum removes human remains from display,” https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/sep/13/off-with-the-heads-pitt-rivers-museum-removes-human-remains-from-display (accessed 15th December 2022)

BBC News, 2020, “Shrunken heads removed from Pitt Rivers Museum display,” https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-54121151 (Accessed 12th December 2022)

Day, Jasmine. 2014. Thinking Makes it So: Reflections on the Ethics of Displaying Egyptian Mummies. Papers on Anthropology 23.1: 29-

Hanchant, D., 2002. Practicalities in the return of remains: The importance of provenance and the question of unprovenanced remains. The dead and their possessions: Repatriation in principle, policy and practice, pp.312-316.

Herewini, T.H., 2008. The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) and the Repatriation of Köiwi Tangata (Mäori and Moriori skeletal remains) and Toi Moko (Mummified Maori Tattooed Heads). International journal of cultural property, 15(4), pp.405-406. [Original source: https://studycrumb.com/alphabetizer]

Morton, S., 2020. Inside the human remains store: the impact of repatriation on museum practice in the United Kingdom.

Smith, L., 2004. The repatriation of human remains–problem or opportunity?. Antiquity, 78(300), pp.404-413. [Original source: https://studycrumb.com/alphabetizer]