One key aspect of our exhibition is the living archive. A living archive is a collection of materials that allows for the expression and documentation of a movement or community. This allows for the archive to be completely unique, the archive of material to change and shift to match the community involved. In our Travelling Gallery exhibition, this concept holds particular value as the bus is able to reach so many different communities. The use of the living archive in the context of the Travelling Gallery allows the exhibit to be set up in a way that allows for pen and paper responses while individuals are on the bus, as well as submissions online. The gallery will be able to grow to reflect those who attend and interact; making it a community space and more personal to those who visit. The living archive is able to be used to interact with diverse audiences.

The concept of a living archive is broad and allows for many different approaches, but centers on the ideas of community and connection. Luisa Passerini wrote about living archives in the 1970s and 1980s in terms of oral history. She discusses the movement during this time focusing on listening to the stories of elders, preserving their past through tape recorded conversations. Highlighting the intersubjectivity of the experience as well as the different connections to sound via recorder rather than to live. She goes on to discuss the different formats that claim the term, from dance performances to the records of musicians (Passerini,1-9). Passerini’s approach to the living archive centers the human connection; not just of the community involved, but the connection between the person who tells the story and the person who records it. This perspective highlights not only the diversity that can be held within a living archive but the personal and intimate nature of it as well.

“From Where I Stand.” Edinburgh Printmakers, https://edinburghprintmakers.co.uk/exhibitions/from-where-i-stand.

Living Archives and the Social Transmission of Memory, written by Amalia Sabiescu, had a similar idea of living archives but took a vastly different approach. Sabiescu writes that “… living archives perform a function of social transmission of memory, which supports building community and identity” (Sabiescu, 498). She goes on to write about the different effects of different types of living archives. She argues that living archives through performances share memories through embodied knowledge and social participation, while archives achieve this through object memory, creating a collective remembering (Sabiescu, 499). This takes the viewpoint that the community not only impacts the living archive, but that the living archive impacts the community in return. That it shapes the way the community grows and the ways it identifies itself, highlighting the importance of what is shared and remembered collectively. That the ‘living archive’ is living. It also makes suggestions about the way that different types of living archives interact differently with the community. This concept is particularly interesting as despite the different memories they create and embody, they are centered on the individual experience becoming a part of the shared community.

The text The Living Archive in the Anthropocene centers on the use of the living archive to create political and cultural change. It focuses specifically on potential ecological changes and how the concept is used by the Interference Archive, which is an independent community archive in New York. The text highlights how a living archive can give voice to communities and allow individuals outside academia to have their voices heard on important topics. That living archives both preserve the past and inspire the future (Almeida, 2-20). This text highlights how living archives allow for communities to address issues that impact them. While at the same time maintaining their collective identity.

A key part of the Edinburgh Printmakers’ exhibition, From Where I Stand, is a living archive. From Where I Stand is an exhibition taking place in India before moving to Edinburgh at some point in the near future, it features prints and multimedia artworks with artists from India and Scotland (From Where I Stand). The living archive running parallel to this is a collection of oral histories of the relationship between India and Scotland. It will be available online as an “extension of the curated exhibition space” (From Where I Stand). This example of a living archive brings a multimedia approach to the living archive. It shows the connection between multiple communities over an extended period of time, giving a unique perspective on the dynamics of this relationship. This digital submission and access allows the archive to be both accessible and personal.

Shalev-Gerz, Esther. “Monument Against Fascism.” Shalevgerz, Esther Shalev-Gerz, https://www.shalev-gerz.net/portfolio/monument-against-fascism/.

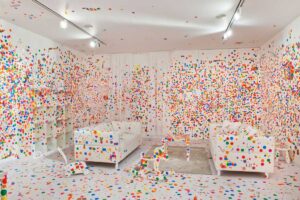

The ways in which the concept of a living archive have been used for communities and artworks vary greatly by type, size, and format, but hold significant insight into the communities that surround them. In Hamburg-Harburg, Germany, a monument against fascism was erected. The intent was that those who lived there would sign their names and put their thoughts there, with the monument slowly being lowered into the ground, in order to give access to more space for their testimonies. This monument gave room for the residents of the area to come together and express themselves. The monument has now been made accessible for viewing next to a text panel (Shalev-Gerz). More recently, Japanese artist, Yayoi Kusama, held an exhibition that took a different direction with this idea. This exhibition was at the Tate in London where visitors were invited to place colorful stickers across an all white living space that was set up (“Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room). Over the course of the exhibition this house-like space was covered in stickers, with the places people were drawn to filling up with stickers quickly. The impactful visual of that transformation creates a sense of community and connection between the visitors. Leaving something as small as a sticker left a lasting sense of involvement in this community and making a place your own.

“Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room.” Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/yayoi-kusama-8094/yayoi-kusamas-obliteration-room.

The living archive offers a unique look into a community, or several communities. It shows connection and changes, the way a community will be remembered as well as the way they chose to remember themselves. It creates and shares information and their, often, interactive nature allows for a personal connection with those who are a part of it. As can be seen through past examples the living archive can be used to interact with wide and diverse groups.

Bibliography

“About.” Interference Archive, https://interferencearchive.org/who-we-are/about/.

Almeida, Nora, and Jen Hoyer. “The Living Archive in the Anthropocene.” CUNY Academic Works, City University of New York , 2019, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/379/.

“From Where I Stand.” Edinburgh Printmakers, https://edinburghprintmakers.co.uk/exhibitions/from-where-i-stand.

Passerini, Luisa. Living Archives. Continuity and Innovation in the Art of MemoryLuisa Passerini. European University Institute, 9/.

Sabiescu. (2020). Living Archives and The Social Transmission of Memory. Curator (New York, N.Y.), 63(4), 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12384

Shalev-Gerz, Esther. “Monument Against Fascism.” Shalevgerz, Esther Shalev-Gerz, https://www.shalev-gerz.net/portfolio/monument-against-fascism/.

“The Monument Against Fascism.” Shalev-Gerz, https://www.shalev-gerz.net/portfolio/monument-against-fascism/.

“The Living Archive.” Edinburgh Printmakers, https://edinburghprintmakers.co.uk/the-living-archive.

“Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room.” Tate, Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/yayoi-kusama-8094/yayoi-kusamas-obliteration-room.

Leave a Reply