Through Frances’ recommendation, I visited the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh over the weekend to witness the exhibition Shipping Roots, which explores three topics (eucalyptus, cactus, and seeds that roam the world) to understand a cultural movement through botany.

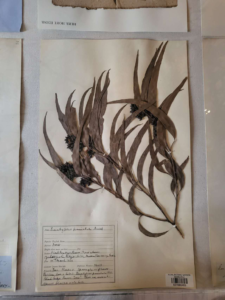

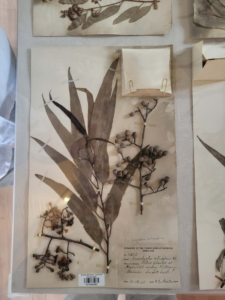

The plant is anchored in the ground, but it is always moving—either intentionally or unconsciously—and the first area depicts the eucalyptus, the fastest-growing and tallest hardwood that the UK imported from Australia, and illustrates the impacts and ramifications of this action.

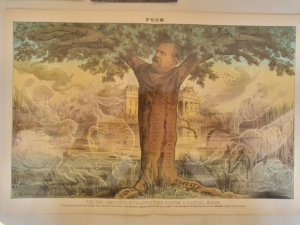

I think this art exhibition does a good job of showing us the economic, artistic and academic value of the eucalyptus species developed through the plundering of the colonies by Extractive colonialism: also known as fetishism, I saw a lot of museum paintings, posters and historical documents about the various species of eucalyptus in the exhibition.

However, taking into account the nuanced link between colonialism and art is necessary in order to examine the problem of British colonialists’ exploitation of eucalyptus from an aesthetic standpoint.

First, the incident might be analyzed from an ecological and environmental point of view. Australia is home to a native tree species, the eucalyptus, which is significant to the ecosystems there. The British’s extensive extraction and transportation of eucalyptus trees not only disrupted and damaged Australia’s ecology, but they also may have permanently altered the country’s natural equilibrium. The British colonizers’ acts were therefore a theft of Australia’s ecosystem and natural resources, which runs counter to the pursuit of art and the idea of care for environmental concerns.

The exploitation and transportation of eucalyptus also resulted in cultural impacts and modifications from a Cultural colonialism. The British pushed their own commercial culture and economic model while controlling and dominating the production and distribution of eucalyptus in Australia, which had an influence on and changed the aboriginal Australians’ cultural and social fabric. In a way that went opposed to the ideal of multiculturalism that art pursues, the activities of the British colonizers also undermined and disrupted aboriginal Australian culture and identity.

While uncertainties surrounding the initial impact signals of human arrival in Australia remain, it is possible to investigate the rapid and severe destruction of Indigenous communities by British invaders in the 18th and 19th centuries and the impact of the loss of their stewardship systems century. Australia faces several significant environmental challenges arising from global climate change and the replacement of indigenous heritage with colonial landscape management following the British invasion of 1788. In contrast to the veritable Garden of Eden described by the first British invaders (Gammage 2011), the continent has proved incompatible with European management paradigms (Kirkpatrick 1999; Bradshaw 2012; Glanznig and Kennedy 2019). Accelerated rates of soil salinization due to over-irrigation (Lambers 2003), soil erosion due to landscape denudation (Bui et al. 2010), catastrophic wildfires due to unimpeded fuel accumulation (Enright and Thomas 2008) and rapid species loss (Woinarski et al. 2015) all point to catastrophic management failures in the Australian landscape since the British invasion.

In summary, the historical event of the development of eucalyptus by the British colonisers needs to be viewed critically in the field of art, reflecting and thinking about the complex relationship between issues of colonialism, environment and culture.

Reference:

Based on this exhibition, I want to investigate the question about how artistic development can take place in a state of respect and equality, so that it does not turn into missionaries and invaders to change the local structure, and the current plan is to start with the history of the development of eucalyptus in Australia.

Fletcher M S, Hall T, Alexandra A N. The loss of an indigenous constructed landscape following British invasion of Australia: An insight into the deep human imprint on the Australian landscape[J]. Ambio, 2021, 50: 138-149.

Bradshaw C J A. Little left to lose: deforestation and forest degradation in Australia since European colonization[J]. Journal of Plant Ecology, 2012, 5(1): 109-120.

Glanznig, A. and Kennedy, M. 2019. Land degradation and native vegetation clearance in the 1990 s: Addressing biodiversity loss in Australia. Response to Land Degradation, 395

Lambers, H. 2003. Introduction: Dryland salinity: A key environmental issue in southern Australia. Plant and Soil, v–vii.

Bui, E., Hancock, G., Chappell, A. and Gregory, L. 2010. Evaluation of tolerable erosion rates and time to critical topsoil loss in Australia.

Enright N J, Thomas I. Pre‐European fire regimes in Australian ecosystems[J]. Geography Compass, 2008, 2(4): 979-1011.

Woinarski, J.C., A.A. Burbidge, and P.L. Harrison. 2015. Ongoing unraveling of a continental fauna: decline and extinction of Australian mammals since European settlement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112: 4531–4540.