The Creative Lull, according to Duchamp, was brought on by artists who ceased coming up with original ideas and were content to follow in the footsteps of their predecessors. However, people can be considered creative when they take examples of predecessors’ artwork and modify them to create their own. This week, we participated in various learning activities, including reading about the definition of play and how it relates to contemporary art, experiencing several scores, and attempting to create a score. Using these experiences as a foundation, this blog will examine how the play might revive the artistic imagination. Can all games fulfill this purpose? If not, what kinds of games are accessible?

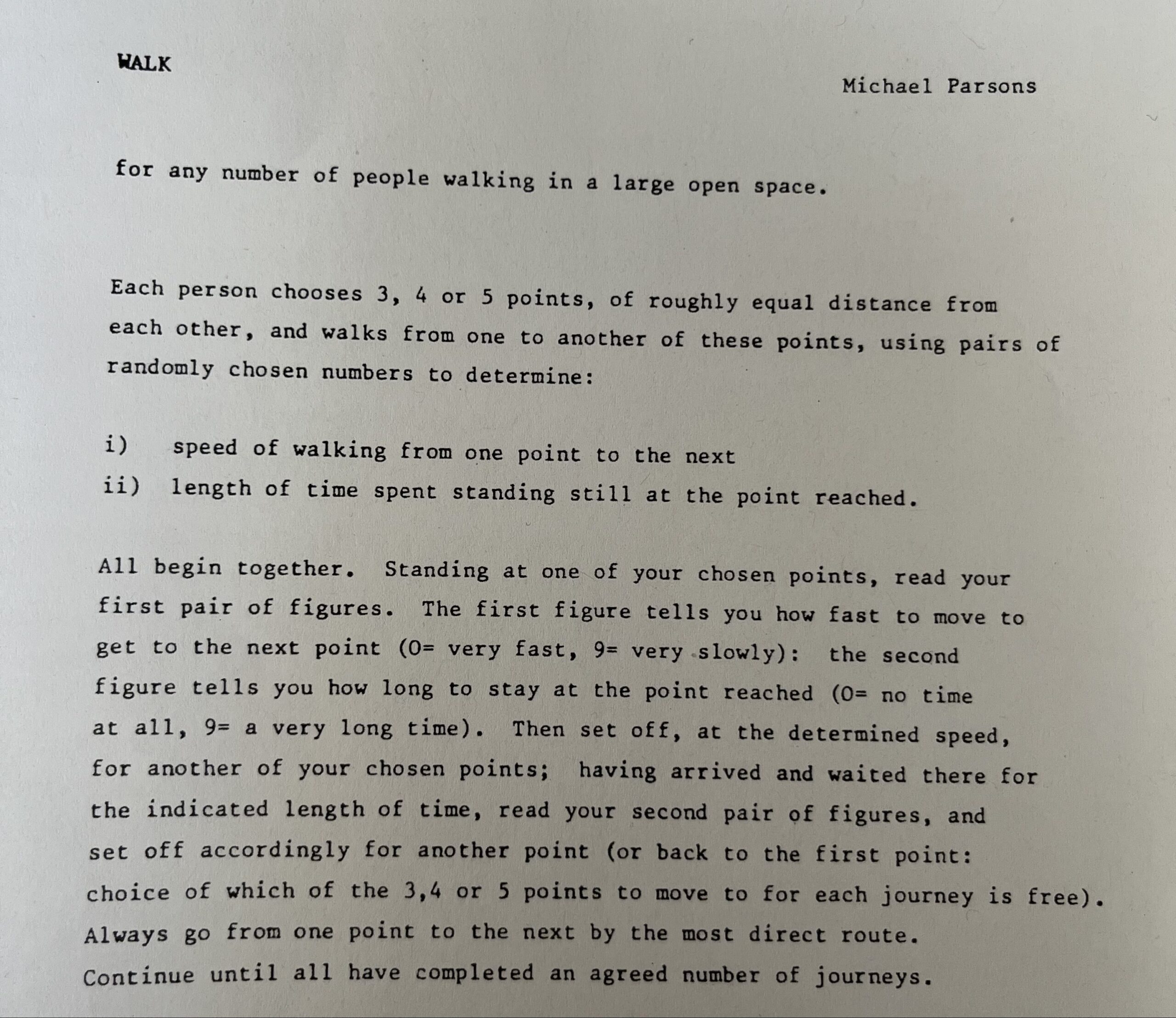

On the first day, we learned what a score was and got hands-on experience with various scores. My basho was assigned to try a score called “walk”. It required each person to choose several locations and two numbers, the first number indicating travel speed and the second representing time spent at the point. We all moved and stayed between the various points during the game at the pace and duration we set for ourselves. Everyone was initially confused because we were unsure when we would be done. Soon, one person started laughing, and then everyone else joined in. I did not grasp the game’s objective or how to determine the game’s winner, so I was incredibly perplexed during the entire procedure. Everyone did not understand what we were doing, and it seemed like an endless, pointless game.

It brought to mind George Brecht’s propositional score “Motor Vehicle Sundown [Event]” (1960), which we were introduced to in class. In it, several vehicles are brought together, and each vehicle executes 22 timed auditory and visual events as well as 22 pauses that are listed on randomly shuffled instruction cards. It looks like a symphony played by the vehicles. This artwork, similar to the score we receive for trying, can only be appreciated by the viewer’s active participation—participating and becoming a part of the artwork requires participants to follow a few straightforward guidelines. However, learning how to play the score did not answer my question; I still find it puzzling how play inspires artistic expression.

After learning about Play and Participation in Contemporary Arts Practices (Stott, 2015), I contrasted two theories’ influences on how to approach play participation in the arts. The first theory is the humanist argument for play, which argues that the most important thing for participants, whether individuals or a group, is to gain pleasure from playing. “When we play, especially when we play with art, we are most fully ourselves and most free.” This reminds me of a few play therapy projects I have worked on with mentally and physically impaired kids. One of the most famous play models is the art-related game, which includes activities like Sandbox Game, sketching without using hands, etc. Humanistic play therapy is based on the theory that kids can express or expose their actual selves to the therapist while playing, finding joy and healing power in games. Similar to Palle Nielsen’s artwork, The Model, it is more crucial to give kids a space where they can exercise complete autonomy and concentrate on their social interaction inside it. This place ‘has given children a break from the pressure of being children, and that is enough.’

However, this idea is not helpful if we want to investigate how play inspires artistic creation. My previous experiences with these games led me to believe that rather than how players apply their creativity to create something new, the participants’ emotions and sentiments are given greater attention during play.

I then focus on the posthumanist argument for play, particularly how Fluxus artists incorporated play into their artworks. According to the Fluxus artists, “The game operated as a programme to which the player ceded control.”(Claudia Mesch, 2006) “The function of the event score was to structure play in order to frame and model everyday situations and actions as fictional or imaginary performances, and to do this in such a way that still might allow for improvisation, collaboration, and stylization. “ Various possibilities can arise in play because the score’s rules or guidelines do not provide relevant details. Play in this instance has the potential to “encourage the creativity of the viewer, listener, or reader: that is, of the receiver.”

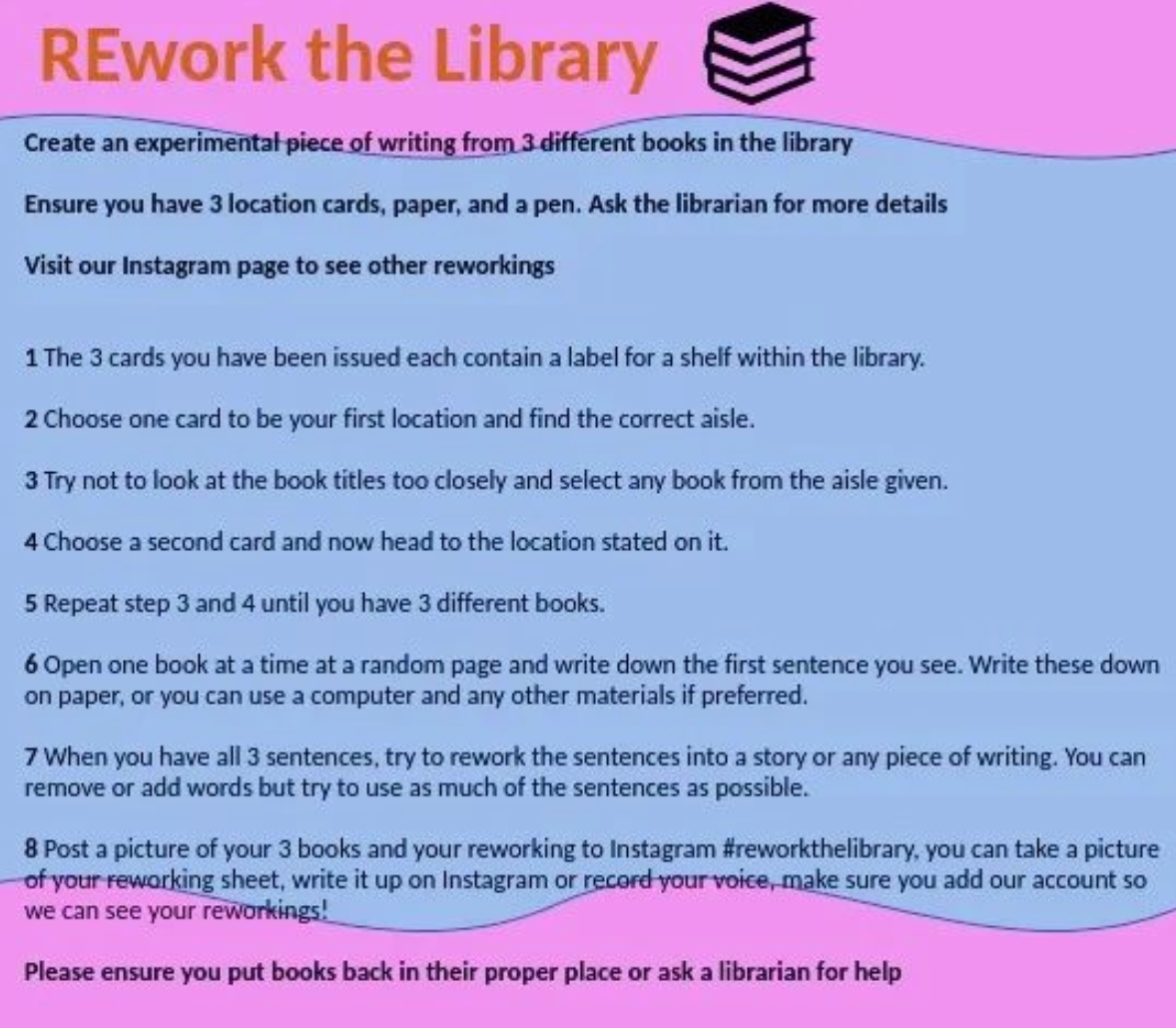

Many Fluxus artworks helped us better understand how play evokes creativity, and we started to consider how we could create a score that would inspire people to be creative again by revisiting, remixing, and changing previous artworks. After some discussion, we chose to build upon the “walk” we had attempted on Day 1 and adjust it to produce our score. For instance, we talked about how one might follow the ‘walk’ construction when one wishes to visit a city. One can choose three locations in the city and the walk speed and length of stay, thus embarking on a different kind of urban exploration. Because of our shared interest in literature, the final score which we designed, called ‘rework the library,’ was based on the idea of exploring a library. Rework the library asked people to select three books at random from the library, turn to a random page and record the first sentence they saw, and try to combine the three sentences into a new text by adding, deleting, or modifying vocabulary to create a new text. After finishing this score, we immediately went to the ECA library to try it out. I chose three books at random—one each about color theory, urban patterns, and photography—and utilized the three phrases I found in each to construct a somewhat bizarre science fiction story.

As the score clearly states, we can only choose books at random, which means that three books could fall into three unrelated categories, making this a difficult task. But I believe that’s what makes the score so appealing. We are not concentrating on what each book is specifically about because there is a limit. With less distraction, it’s easier to focus on how we might develop new stories using limited resources. Following the score’s instructions, we revisited the text passages in front of us, trying to structure them and reorganize them into new passages, which exercised our creativity to a great extent. As it turned out, we were able to adapt other people’s work through this series of processes and create something completely different from the content of these.

Thinking about the possibility of doing this score differently and changing this to benefit others, we also thought this score could be adapted to various situations, potentially as a new method of producing artwork. For example, an artist might choose three pieces of art at random from various fields or genres, extract the creative material, the technique, and the theme from each piece of art, much like extracting sentences from a book, and then try to modify and reassemble these elements into a new piece of art.

In conclusion, the score, as the initiating process of the game, sets the rules of the game so that the artist can follow the instructions of the score and experiment with different methods of revising, remixing, and modifying existing artworks, thus reconfiguring them into new articulations of knowledge and provocations for future action. At the same time, the score, which is a helpful tool to stimulate the creativity of artists, can also be adapted into a new score to accommodate various creative requirements.

Citations used in this page:

- Stott, T. (2015). Play and Participation in Contemporary Arts Practices (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315724782

- Car Concert: Motor Vehicle Sundown by George Brecht. www.youtube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zj0pxipGNr8. Accessed 15 Oct. 2022.

- The Double Negative » Palle Nielsen: The Model. http://www.thedoublenegative.co.uk/2014/01/palle-nielsen-the-model/. Accessed 15 Oct. 2022.

- Claudia Mesch, ‘Cold War Games and Post-War Art,’ Reconstruction 6.1(Winter 2006), http://reconstruction.eserver.org/061/mesch.shtml.

For more details about what I do in this course, please click the link below:

s2444438

20th October 2022 — 4:49 pm

This blog discusses how adaptations of games can stimulate the creativity of artists, in the context of the author’s classroom experience. However, this article does not seem to respond adequately to Duchamp’s words; I would like to know what kind of understanding the author has of Duchamp’s views and what attitude she takes towards them. Also, whether it is humanism or post-humanism, they mostly discuss the state and agency or creativity of the players, but rarely the developer or designer of the game; the author’s sudden jump from post-humanism and Fluxus to talking about the creativity of the artist strikes me as a bit abrupt; perhaps the author should elaborate further on this connection. However, the author’s experience of adapting games is fascinating to me, and it is a compelling example of how creativity can be born from the recreation of art.

s2414944

20th October 2022 — 5:38 pm

“With less distraction, it’s easier to focus on how we might develop new stories using limited resources. ” This sentence enlightened me a lot. I am often anxious about that there is no enough resources for me to draw or write something, but I never try to use less to make more. It seems that the members just used 3 sentences to create but actually they also used much imagination to create and recombined these sentences logically. It is interesting and creative.

s2341902

23rd October 2022 — 4:57 pm

The score designed by Chenyan is very interesting and opens up more possibilities for art making, but I might be confused as to why the city is linked to the library and I am very curious as to why the library was chosen? After making up the story does this story have anything to do with the city