Every year on 28th October, Cyprus celebrates the anniversary of Metaxas’ “Ochi” in response to the ultimatum of the Italian authorities that requested Greece’s participation on the side of the Axis powers in the Second World War. On this day Greek people celebrate the “strength” of our Greek ancestors against fascism – the heroic resistance of 1940, with anniversary parades and a public holiday.

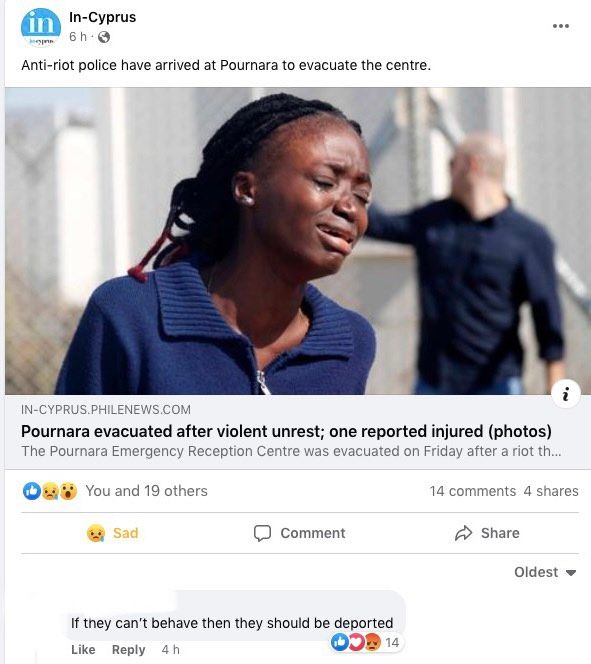

However, this year was different than the previous ones, unfortunately, this year on October 28, serious incidents broke out at the Pournara First Reception Center, where they escalated into fires, resulting in the evacuation of the camp. Due to the national anniversary parade, the Police had turned their attention to Lord Byron Street, resulting in the Forces not arriving as timely as they should have. But reporters did arrive on time and the spread of the events on the internet was lightning fast.

Misinformation on migration is not new, every time there is a news story about an incident, the narrative of the story has a bad protagonist – the immigrant, “the foreigner who does not respect our country”. I have observed countless times missing information and exaggeration that spreads racism and alienation towards foreigners. When receiving the news about something that occurred, we have information only about “the result” and the climax of the situation – we have no clear information about what led there. What caused it and why those people reacted the way they did? Given that this is a very sensitive and delicate matter, obviously confidential information cannot escape the “doors” of the camp. But traditional media could at least maintain a neutral and objective stance.

“The terms “misinformation,” “disinformation,” and “propaganda” are sometimes used interchangeably, with shifting and overlapping definitions. All three concern false or misleading messages spread under the guise of informative content, whether in the form of elite communication, online messages, advertising, or published articles.” (Guess and Lyons, 2020 p.10). It is becoming increasingly clear that almost any interaction, beyond first hand perception, is filtered either through institutions, like media and government, or other people – to some extent. Making objectively verifiable truth, beyond the scope of the scientific method, an unobtainable aspect of knowledge. This exemplifies why empirical research has such a vital part to play. Giving clear boundaries to what is under its purview, by exclusively dealing with directly verifiable claims, it strengthens confidence through a reasonable consensus of the relevant experts. This, however, does not eliminate disagreement over facts, although it may help curtail a majority of the issue. This leads to unverifiable claims not being classified as misinformation, due to the narrow definitions.

So on the day that the Greek people of Cyprus celebrate the resistance against fascism, a part of the Cypriot population decides to participate in the online court against immigrants with “fascist” and racist comments. People who suffered wars and immigrated abroad for a better future choose to close their doors to asylum seekers from third countries. “Whereas the fascist authoritarian extreme right was a marginal political phenomenon in many democratic countries 30 years ago, it has in a relatively short period of time become a strong, powerful and emboldened segment of the mainstream right with ideas and viewpoints once considered deviant and morally repugnant today confidently asserted as the new common sense and increasingly shaping public policy as it only suffices to refer to current immigration policies.” (Cammaerts, 2022 p. 731). In this case social media plays devil’s advocate and everyone uses the platforms to vent their anger.

The media forgets to mention that Cyprus receives funds to maintain the camp, a first reception centre that houses twice as many people as the infrastructure can handle.There are traffickers who profit from the “importation” of asylum seekers into Cyprus. The status quo is therefore maintained with The European Union, in essence, paying to shift the burden of the immigration crisis towards border countries, like Cyprus, with these countries having an incentive to keep the current system in place in order to maintain funding.

To be objective and fair, many of the asylum seekers do not meet the criteria needed to be considered appeals. According to the Cypriot Refugee law, “a refugee is recognized as a person who, due to a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality or membership of a specific social group or political opinions, is outside the country of his origin and is unable, or, due to such fear, is not willing, to avail himself of the protection of that country, or a person, who has no nationality, who, while outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of these circumstances, is unable or, on account of the fear thereof, is not willing to return to it and to which Article 5 does not apply.”

The Cypriot authorities speak of an attempt from Turkey to change the demographics of the island since now the percentage of asylum seekers is equivalent to 5% of the total population of the Republic of Cyprus. The political game continues with both parties blaming each other without making substantial decisions. On the other hand, residents of the area are frightened by the situation prevailing in the centre and immediately request the intervention of the president, while others request the removal of the camp from the village of Kokkinotrimithia.

So how do social networking platforms contribute to misinformation? Is the internet a place where you can abdicate responsibility and create your own version of what’s real? What is the truth and how can you distinguish it when you are the recipient of various political agendas?

References:

Cammaerts, B. (2022). The abnormalisation of social justice: The ‘anti-woke culture war’ discourse in the UK. Discourse & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/09579265221095407

Guess, A. M. and Lyons, B. A. (2020) “Misinformation, Disinformation, and Online Propaganda,” in Persily, N. and Tucker, J. A. (eds) Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (SSRC Anxieties of Democracy), pp. 10–33.

Ο περί Προσφύγων Νόμος του 2000 – 6(I)/2000 (no date). Available at: http://www.cylaw.org/nomoi/enop/non-ind/2000_1_6/full.html (Accessed: October 29, 2022).