MALAYSIA is currently endeavouring to become the first nation to successfully combat the tobacco pandemic through the Generational Endgame (GEG) campaign. The effort to end the scourge of tobacco has been languishing since 2003 as the Ministry of Health (MOH) struggles to establish a standalone Act. Tobacco control has been a subsidiary bill under the Food Act 1983 [1]. The Control of Tobacco Products and Smoking Bill 2022 if passed will permanently ban any Malaysian born after 2007 from purchasing and using all forms of smoking material including reduced-risk products (RRPs) such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) and vapour (vapes) products [2]. Although this mammoth effort warrants applause, it has also garnered criticisms from major industry players citing that the prohibition is unnecessary, ‘criminalises children and exacerbates the black market phenomena.

Accounting for 22% of cancer deaths, tobacco use is regarded as the leading cause of cancer in Malaysia [3]. Cancer incidences have risen from 115,238 (2016) to 128,018 (2020) and are projected to double by 2040 [4]. Health Minister, Khairy Jamaluddin’s, ambitious intention to closely parallel the move by New Zealand would undoubtedly reduce the number of smoking-related illnesses which are

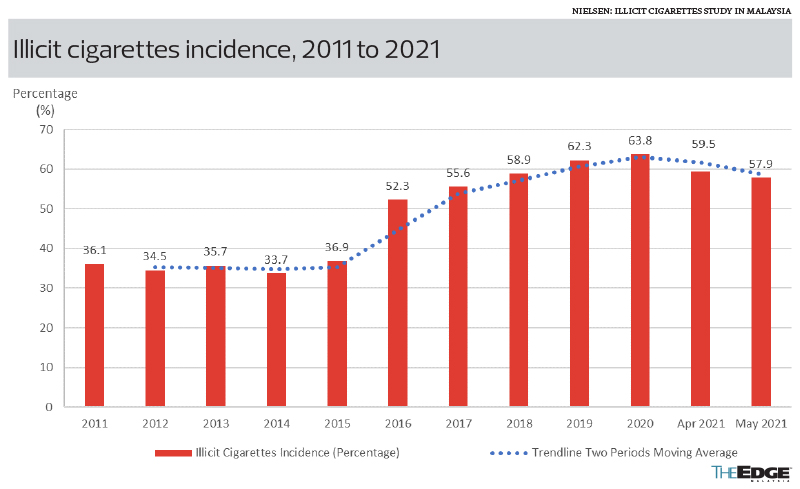

considered preventable diseases. However, The Confederation of Malaysian Tobacco Manufacturers (CMTM) which comprises British American Tobacco Malaysia (BAT Malaysia), JT International (JTI Malaysia) and Philip Morris Malaysia (PMM) highlights that not only will the bill revoke the rights of adult consumers solely based on their birthdates, the prohibition would also fuel the black market which at present, is already dominating 57.9% of the total tobacco market (figure 1) [5].

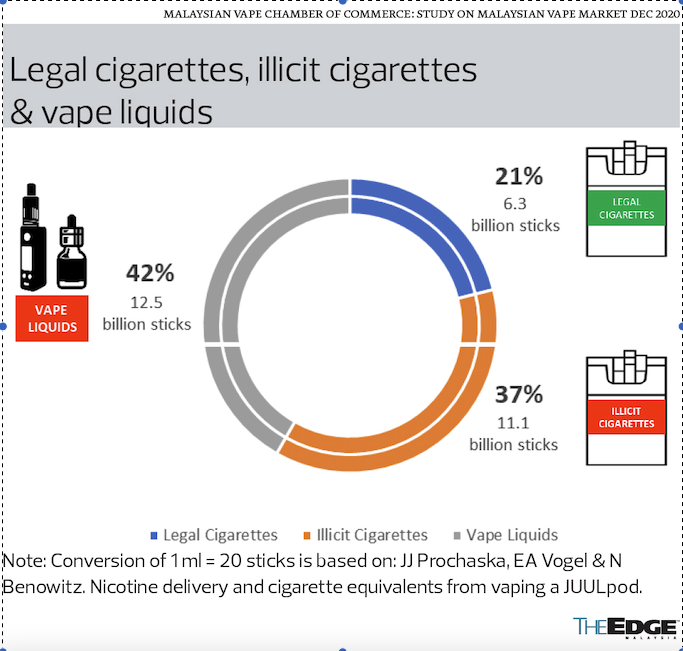

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as the Retail and Trade Brand Advocacy Malaysia Chapter (RTBAM) and lobby groups such as Malaysian Vapers Alliance (MVA) and Vape Consumer Association of Malaysia (VCAM) also concur with this position citing that the illicit market is actually higher (about 79%) as it includes counterfeit vape liquids [6].The government would be facing another national crisis; controlling the sheer volume of nicotine liquids smuggled into the country (figure 2) [7]. Malaysia is also the largest manufacturer of unregulated vape liquids globally. Therefore, apart from poor quality products, the 1.12 million vapers are exposed to more harm from unregulated nicotine dosage [8]. CMTM also highlighted that revenue generated from illicit trading may also fund other criminal activities [9].

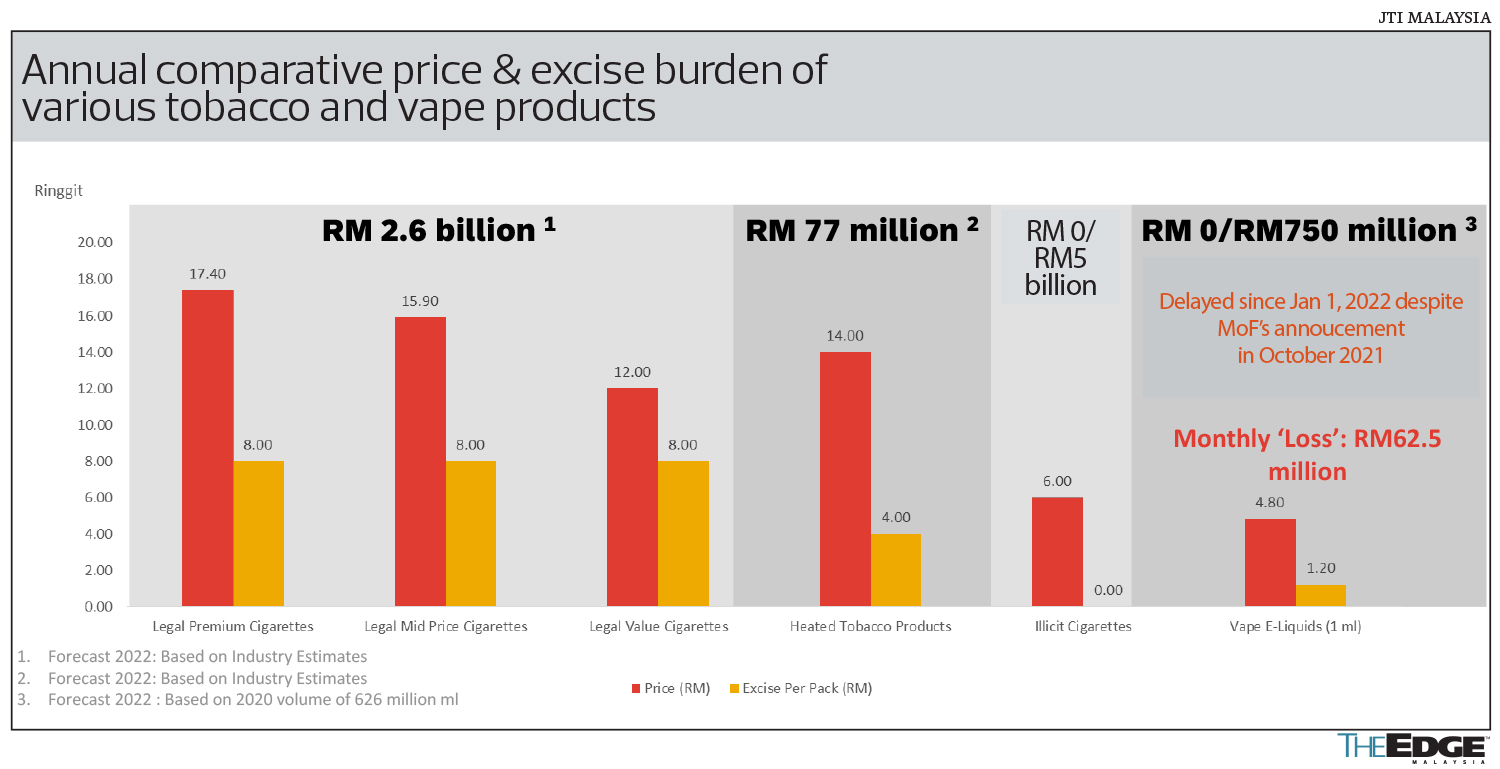

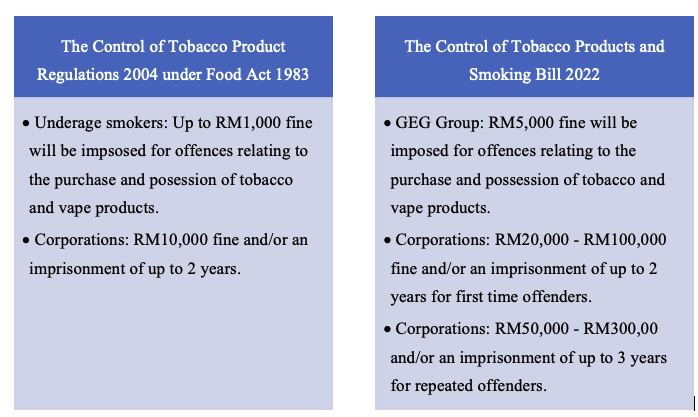

In addition, CMTM, MVA and the Malaysian Vape Chamber of Commerce (MVCC) state that more than RM5.75 billion will be lost annually due to tax leakages (figure 3) [10]. Proponents of this bill state that the above pales in comparison to the RM16 billion spent by the government and private sector to treat smoking-related diseases. Within five years of implementation, the government would save RM1 billion annually from the health budget [11]. They argue that this will greatly aid Malaysia’s current financial situation. A memorandum by the Consumer Choice Centre (CCC) was submitted to Parliament in October 2022 protesting the Bill citing that such extensive enforcement powers and harsh penalties burden the poor and criminalise children (figure 4) [12].

Khairy Jamaluddin argues that the penalties for minor offenders have already been included in the existing regulations. Penalties are only in the form of compounds, not prison sentences. In fact, minors who commit the offence will only receive a RM50 fine [13]. Furthermore, authorities cannot register it as a criminal offence. These claims are misleading as the intention is to protect the future generation from acquiring any smoking habits and nicotine addiction.

The Malaysian Vape Chamber of Commerce (MVCC) has also urged the government to reconsider the implementation of the Bill as

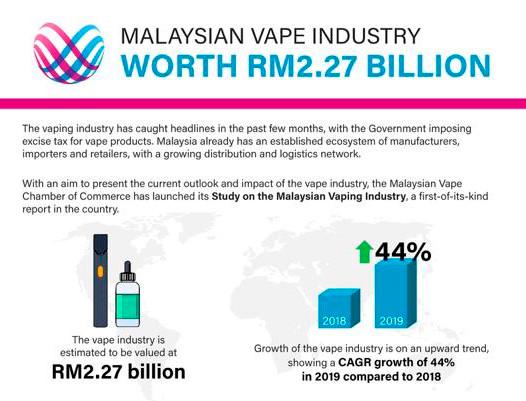

Malaysia’s substantial vaping industry (figure 5) [14] has played an important role in the growth of local entrepreneurs. By enforcing proper regulations, the government may benefit from a positive multiplier effect, particularly on the economy (figure 6) [15].

The pursuit towards a smoke-free nation should take into account the circumstances of the implementing country. Issues surrounding implementation must be considered. In a country where corruption and double standards within law enforcement are visible and rampant, stringent penalties may encourage bribery and misuse of power. Legislators have also received political assistance from the industry in the past [16]. Second, instead of focusing on prohibition, Malaysia could focus on harm reduction. Akin to New Zealand’s Bill, e-cigarettes and vapes should be excluded and regulated as part of a harm reduction programme. Malaysia’s success in tackling opioid-related issues through establishing and strengthening its methadone programmes is a testament that the same effort should be replicated for tobacco-related issues [17]. Third, public consultation should be included and it must involve groups and individuals at all levels. Not just those in power. It is therefore insufficient to blindly propose a policy and insist that it is ‘right’ [18]. Public outrage, witnessed when the Bill was first presented in July 2022, shows that support cannot be attained through demand or coercion.

Although the Bill was referred to a parliamentary select committee for further scrutiny, work on the Bill should not cease. If this ground-breaking legislation can be implemented successfully, not only will the current 12.33 million children (7.53 non-smokers and 4.8 smokers) be able to benefit from a healthier future [19]. Malaysia will also be able to create a tobacco-free generation and hopefully, end the tobacco game once and for all.