The first two weeks of April I spent travelling through Patagonia. In Trevelin we stayed with a former student of Mariana Enríquez, one of the authors I write my PhD on. Wherever I go in Argentina, my PhD topic is never far off! In this post I want to sketch what April has been like through a few literary anecdotes.

The travels of María Negroni

During my first week in Buenos Aires, multiple people recommended me El corazón del daño by María Negroni, writer of poetry, essays, and novels and translator. A friend I met at the book club thought it would be a good holiday read (not sure why, as it is an essayistic novella on childhood trauma and complex mother-daughter relationships), so she sent a scooter to drop off the book at my place before I left. I didn’t know you could hire drivers to pick up and drop off books (and other objects, of course), so I was confused when Gabi messaged me to let me know that a driver would turn up at my door with a novella in hand. Nevertheless, I had to admit that this is a highly efficient practice, and contentedly I put the book in my backpack.

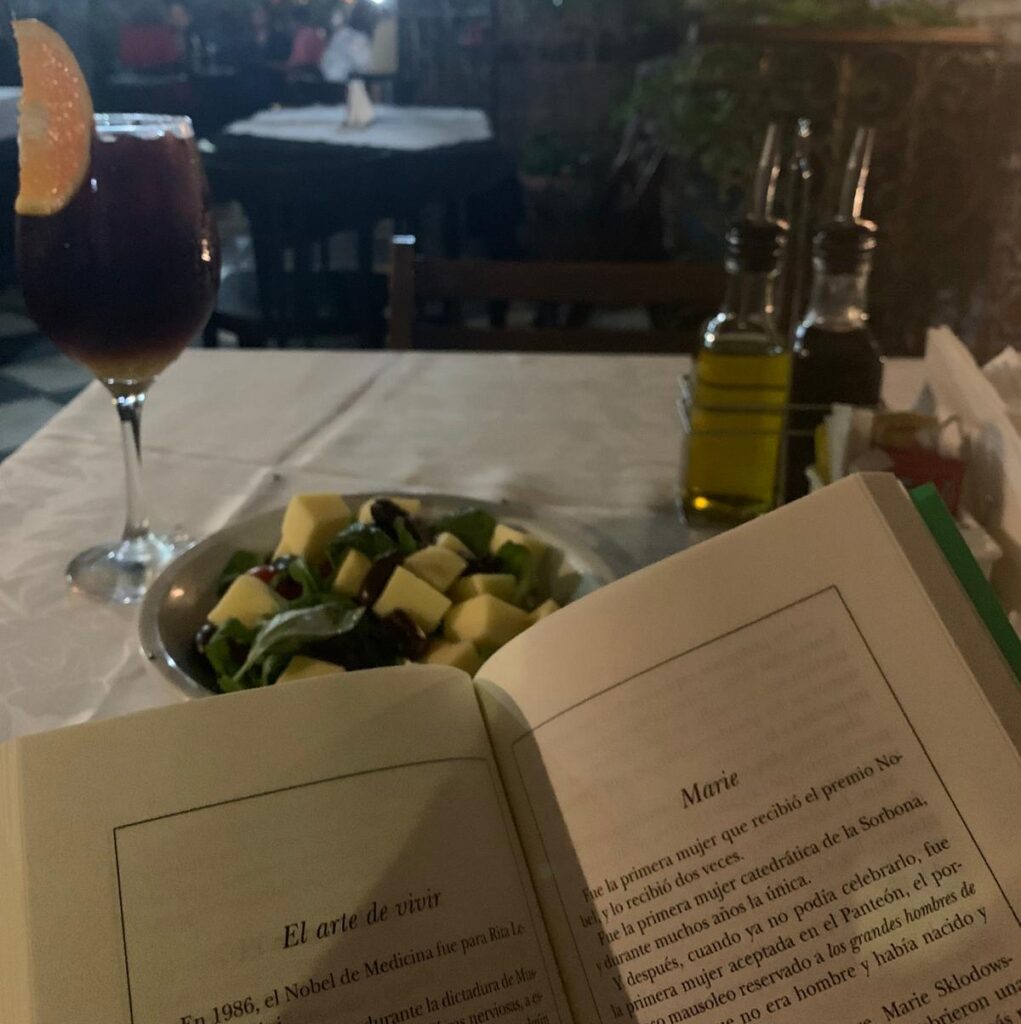

Like every tourist travelling to El Calafate, we did not want to miss Perito Moreno, arguably Argentina’s most famous glacier, and for good reason. A quick search on the net will present you with plenty of blog posts on this natural phenomenon, so I will just say it was one of the most impressive phenomena I have ever laid eyes on (the photo below speaks for itself).

Our taxi driver, Dario, drove us to the national park and we agreed we would drive back four hours later. Although he was the one to suggest this arrangement, I was worried those four hours would contribute massively to a bore out. Upon my question of how he would entertain himself, he answered that he brought a historical fiction novel he was not really enjoying. I offered to leave the book I had in my backpack and he gladly accepted my offer. Of course, I forgot to ask for it back once Dario dropped us off in the centre of El Calafate… Thanks to WhatsApp, another such convenient invention, I got Gabi’s book back.

Villa Ocampo

Back in Buenos Aires, we decided to spend our Saturday in San Isidro, the province’s most affluent neighbourhood. One hour by train from San Telmo, where I live, this day out was mostly welcome because of its tranquility. According to a study by the WHO, Buenos Aires is the noisiest city in Latin America, with decibels regularly surpassing healthy noise levels. It can get tiring, so I welcome every chance to get some peace and quiet.

The second reason why we really wanted to visit San Isidro is because Villa Ocampo is located there. Villa Ocampo was the summer residence of the Ocampo family, but oldest daughter Victoria spent the most time here. Sister to the famous author Silvina Ocampo, Victoria’s legacy in the cultural field should not be underestimated: she was writer, critic, published the influential literary magazine Sur and co-founded the Argentine Women’s Union in 1936.

Villa Ocampo exhibits Victoria’s intensive collaboration with UNESCO and her contributions to the arts as patron and philanthropist. Moreover, Stravinsky, T.S. Eliot, and Graham Greene – to name but a few – stayed at Victoria’s place during their visits to Buenos Aires. In the Belle Époque house, we got to inspect her library (including the entire oeuvre of Virginia Woolf, and Finnegan’s Wake ostentatively on display) – but not from too close as the books are protected by a glass wall and an alarm. The library and the desks full of old copies of Sur leave no doubt as to the far-reaching influence the Ocampo sisters have had on Argentina’s 20th-century literature.

Ukranian diaspora in Argentinian literature

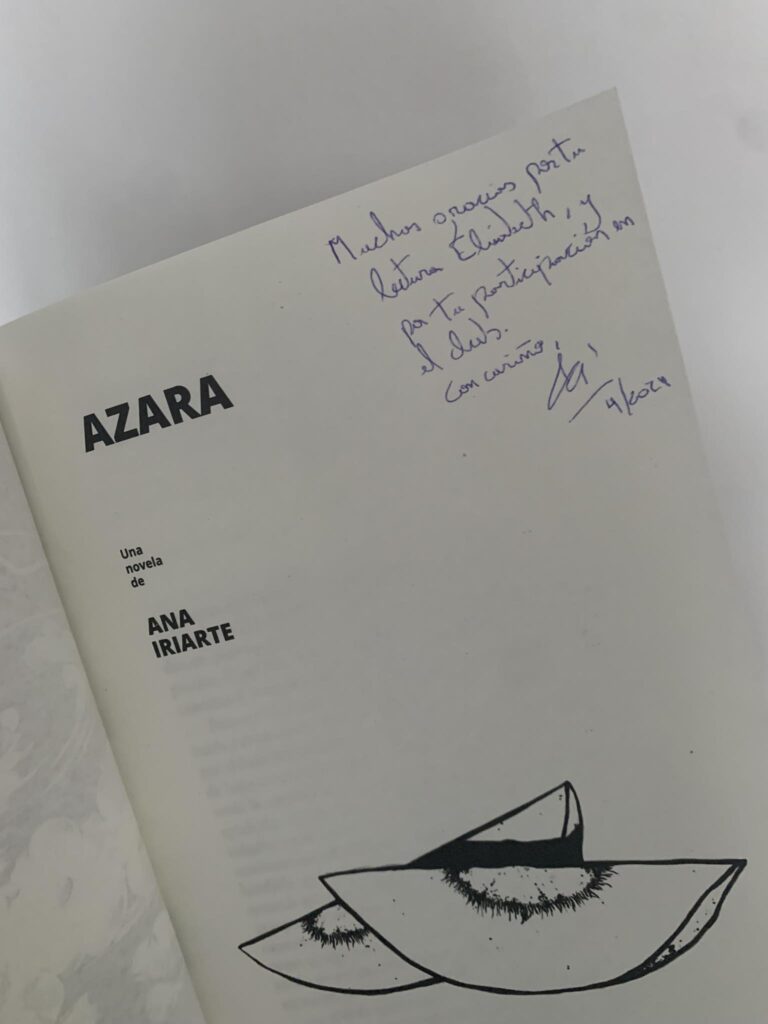

The weekend after, I went back to the book club at a bookshop in San Telmo. This time, we read Azara by Ana Iriarte. The story is about a teenage girl who travels to a village in Misiones, because she found out that she was born there and sold to adoptive parents. Although the novel is about trauma and uprooting, Iriarte also describes the tightly knit community of Ukranian descent and the hybrid culture in the village.

What struck me during the discussion was that no one linked the novel to the war or the current displacement of Ukrainians. At the end of the discussion, I mentioned that I found it important to read stories like this one, because they serve as reminders that Ukrainian culture – like any other – deserves to be remembered and discussed in terms that go beyond conflict. Many people in the room seemed surprised and said they had not even thought about the war while reading it. I suppose that this has to do with Argentina’s geographical distance from Europe and Ukraine? How many conflicts am I forgetting about just because they are physically or mentally distant?

On a brighter note, Ana Iriarte attended the book club, as did some of her former students! 😊 I spent most of the time too nervous to ask questions, but gladly listened to her speak about her personal relationship with Azara and how she went about turning it into a novel.

The coming weeks, I will likely be spending my evenings at the Buenos Aires Book Fair, attended by many of the authors I hold in high regard. Exciting!