How open are MOOCs? Part 2

MOOCs and OERs were born of an optimism that Brown & Adler explore in ‘Minds of Fire’, and were a pragmatic, ambitious initiative to change the essence of education. Eminent institutions the world over embraced the concept of MOOCs as a transformative exercise in providing free education for those who want it.

MOOCs Target Audience

MOOCs are meant to be fully ‘open’, so that anyone can take part. Indeed, this level of free access is still a reality. Whilst anyone can join, Cottom highlighted that in the U.S., typical MOOC participants tend to be white, male, middle-higher class learners with formal credentials and economic resources. They are pragmatically taking advantage of the opportunities afforded by MOOCs. In this interesting blog, we are also reminded of the millions of under-privileged people who simply want to learn.

“MOOCs are trying to make better quality education available to a great mass of people who are currently “non-consumers” of education and such quality is currently superior by far to whatever they may be getting right now.”

Yet are MOOCs pretending to be something they are not?

‘Grandpa, what was the biggest upgrade you saw when you went to school?’

When you sign up to a MOOC, you are given the ‘free’ option and then a choice of ‘upgrading’. This is where, I think, the lines become blurred between being offered a philanthropic opportunity for self-improvement and becoming part of a financially motivated system. If you are a canny internet user who is experienced in dodging the upgrade button, the MOOC does everything it says on the tin. However, if you are a naive participant who believes that the MOOC is replacing a higher education qualification from an institution, you will be disappointed and also a few dollars poorer. In that respect, the MOOCs are perhaps not quite as ‘open’ as they could be. MOOCs were once the domain of well-known institutions who wanted to share knowledge. As with all initiatives, others have jumped on the bandwagon and there will be examples of MOOCs that are not as educationally rigorous as they might be.

What is in it for the educators?

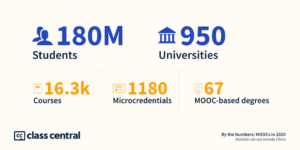

Now in its ninth year, the modern MOOC movement has crossed 180 million learners, excluding China. https://www.classcentral.com/report/the-second-year-of-the-mooc/

numbers of registered users in the top 4 MOOC providers https://www.classcentral.com/report/the-second-year-of-the-mooc/

MOOC initiatives are now more than pure philanthropic ventures; they are highly advantageous for the institutions, improving reach and access, as well as building and maintaining brand. MOOCs can reduce costs or increase revenues, whilst hopefully improving educational outcomes. MOOCs also are conducive to conducting research on teaching and learning. The very proliferation of MOOCs shows how lucrative the business has become. I found a list of 49 providers, each providing thousands of courses.

Coursera used to be completely free. Now they make over $100+ million dollars every year. Does this financial motivation change the openness of MOOCs?

Social justice and accessibility

The issues of social justice and assumptions of technical accessibility impede full openness in MOOCs.

Kibera slums, Nairobi

In an ideal world, the OER movement and MOOCs should be enabling educational equity and offering transformative solutions. However, if you have situations where there is a poor infrastructure, a lack of ICT skills, and a lack of basic implementation skills, you will be unable to access and use both OERs and MOOCs successfully. This is certainly the case in a country like Kenya, and indeed, Kenya is used as an example in Hodkinson-Williams et al (2017) article. The Kenyan government is exploring ways of using OERs to address social injustices in ameliorative ways (perhaps one day transformative), such as improving access to educational materials for students. The Kenya Education Network (KENET) has an interesting summary of why they are advocating embracing OERs, talking of education as a right and not a privilege.

Hodgkinson-WIlliams alludes to the ‘current domination of Western-orientated epistemic perspectives’ and questions who is deciding what counts as worthwhile knowledge. This is interesting to apply to how open MOOCs are. The hegemony of the West continues to dominate amongst MOOC providers, with a vast majority orginating in the USA. However, the balance is slowly changing. There is Swayam in India, The University of Cape Town runs MOOCs, and I found many that are Chinese, Korean and Russian. Presumably the educational content of the MOOCs will therefore be more locally relevant and there will be less of a danger of culturally problematic knowledge transfer. (Hodgkinson-Williams).

To conclude

To summarise my conclusion, I choose this comment where Ozturk (2015) notes that:

… in line with the theoretical underpinnings of the OER movement MOOCs initially included key features of connectivist pedagogy like autonomy, community participation, openness and diversity but the newer MOOCs, which are underpinned by financial models and informed by instructivist and cognitivist pedagogies, suggest that the “learning praxis [of] MOOCs has been commodified.

My final observation would be that this commodification should not solely imply negativity. The pedagogies used within MOOCs maybe be veering away from the positive features of a constructivist perspective. The motivations for MOOCs may be increasingly financial. Nevertheless, MOOCs offer opportunities for education that were previously unavailable, and that has to count for something.

Sources:

Bayne, S., Knox, J., & Ross, J. (2015). Open education: the need for a critical approach. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(3), pp. 247-250.

Brown, J. S., & Adler, R. P. (2008). Minds on fire: open education, the long tail, and Learning 2.0. EDUCAUSE Review, 43(1), pp. 16–32.

Hodgkinson-Williams, C. A., & Trotter, H. (2018). A Social Justice Framework for Understanding Open Educational Resources and Practices in the Global South. Journal of Learning for Development, 5(3), 204-224.

Czerniewicz, L., Deacon, A., Glover, M., & Walji, S. (2017). MOOC-making and open educational practices. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29(1), pp. 81-97.

Czerniewicz, L., Deacon, A., Walji, S., & Glover, M. (2017). OER in and as MOOCs. In Adoption and Impact of OER in the Global South Hodgkinson-Williams, C. & Arinto, P.B. (Eds.) (Capetown & Ottowa, African Minds): pp. 349-386.

Knox, J. (2013). The limitations of access alone: moving towards open processes in education. Open Praxis, 5(1), pp. 21-29.

McMillan Cottom, T (2015).

ICDE, UNISA. Oct. [YouTube video of a keynote presentation at the 26th World Conference for the International Council for Open & Distance Education, 13 – 16 October 2015, Sun City, South Africa]

There is an interesting tension between the espoused values of MOOCs in terms of opening up education and the commercial basis for specific MOOC providers. Coursera is a venture capital backed firm that is required to (eventually) generate financial returns to its investors (Coursera’s last funding round in July 2020 gave it a valuation of $2.5bn so an IPO should have a higher valuation of the value the company) while FutureLearn is expected to generate profits that can be returned to its owners that include the UK Open University (who were initially FutureLearn’s sole owner). So your points about the commerciality of the MOOCs you tried are well founded. It is worth noting, however, that neither Coursera nor FutureLearn have generated a profit. The Ozturk quote is well chosen here.

Your points about access to infrastructure, devices and connectivity are really important ones especially in the context of the sustainable development goals(including SDG 4 on access to a quality education. Would digital education be the key way to deliver on SDG 4 or could it be used as a way for governments to claim they are providing access to all without doing the necessary but complicated and costly work around the availability of connectivity and devices? The One Laptop and KENET do point to the innovative and impactful work being done to address digital divides. The importance of providing MOOCs from alternative epistemic perspective is an important one. Yet, do MOOCs also play a part in soft-power projection and can be mobilised in to wider foreign policy considerations?