(All credit given to Alicia Keys for the title- click link to listen)

Cynthia Enloe’s Bananas, Beaches & Bases- arguably one of the most influential pieces of feminist scholarship in the recent decades, starts a bit more differently than previous works mentioned in this blog, with the likes of Plato, or Baudrillard. Enloe cannot afford to conjure utopian landscapes with caves and maps, perhaps giving into the urgency of the reality that is being a woman.

And so, this ‘train of thought’ as one might call it, begins in 2012, when the Tazreen Fashions Garment factory in Bangladesh, caught fire. Once the fire alarm was sounded in factory, the workers, consisting of several women, realized they had been locked into the factory, preventing them from escaping.[1] 112 people, mostly women, died in that fire.[2] Why had they been in there to begin with? Because these women workers were providing cheap labor (minimum wage of $37/month) for clothing companies such as H&M, Zara, GAP, C&A, unprotected by laws, uninformed of their rights.[3]

Alvarez provides one of the simplest explanations for epistemic violence- “violence exerted against or through knowledge, […] probably one of the key elements in any process of domination”.[4] Wishful thinking, yes, but had those workers not been working in an environment with such an asymmetrical distribution of knowledge on rights, safety, and regulations, one can imagine they would still be alive today. While instances of epistemic violence, particularly towards minority groups, and women have become numbingly commonplace- the realization that our lives are no longer restricted to the ‘offline’, brings with it an entirely new array of questions.

It was when listening to Nanjira Sambuli talk at the BBC 100 Women London Conference that even the possibility of digital gender inequality crossed my mind. Afterall, like Turkle claimed, was the digital space not supposed to be a liberatory platform that allowed the user to detach themselves from ‘restraints’ of the physical realm, in which “women could explore, resist, subvert and create new subjectivities and identities”[5]? While it was made painstakingly clear that this was not the case, Nanjira gave the facts as they were: millions of women are not even part of the digital space.

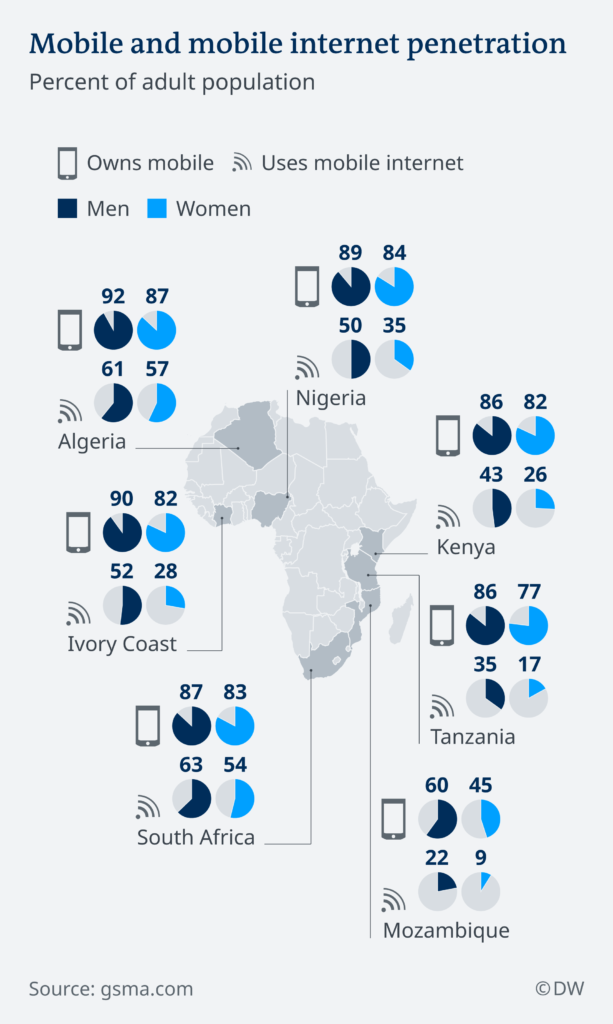

To put this into perspective- there is an entire new realm that women are not part of. Yes, it is impulsive to think of the codified Instagram model when reading a sentence like the one above. However, this only strengthens the second point: since when does a single demographic of economically independent, geographically ‘advantaged’ individuals constitute the entirety of the gender? If so, where does Aissata, who is scared of her husband’s reaction to her having a phone, or Agnes, who has to choose between buying a mobile phone or investing in a goat for her family, fall?[6]

Barring the ethics of the question, it’s worth considering what implication the absence of women has on digital society. Can the Feminism that battles for women factory workers in Bangladesh, turn a blind eye to this reality? While we continue to debate (or excavate) instances of epistemic violence in the non-digital, feminism faces the greater peril of ignorance (or complacency) in the digital. Green and Singleton could not be more right when they said: “it still falls to feminists to put gender (back) on this (new) agenda”, so that the progress made by those like Enloe, is not lost.[7] It is, perhaps the greatest epistemic violence of all, where women have no access to knowledge, opportunities, and content the digital can offer them.

[1] Manik, J. & J Yardley (2012) Bangladesh Finds Gross Negligence in Factory Fire The New York Times.

[2] Enloe C. (2015) ‘Reflections’ interviewed by Dubravka Zarkov Development and Change 46(4): 893–912. DOI: 10.1111/dech.12168 p.905

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/dech.12168

[3] Manik & Yardley 2012

[4] Galván-Álvarez, E. (2010). Epistemic Violence and Retaliation: The Issue of Knowledges in “Mother India” / Violencia y venganza epistemológica: La cuestión de las formas de conocimiento en Mother India. Atlantis, 32(2), 11-26. p.12

[5] Green E., & C. Singleton (2013) ‘Gendering the Digital’: The Impact of Gender and Technology Perspectives on the Sociological Imagination. In: Orton-Johnson K., Prior N. (eds) Digital Sociology. Palgrave Macmillan, London. P.37

[6] Frolich S. (2019) Africa’s Mobile Gender Gap: Millions of African Women still offline DW

https://www.dw.com/en/africas-mobile-gender-gap-millions-of-african-women-still-offline/a-49969106

[7] Green & Singleton 2013, 40