Released in 2002, this four part series by Adam Curtis explores how the ideas of Sigmund and Anna Freud revolutionised how businesses operated and related to their consumers through public relations (PR), a field invented by Freud’s nephew Edward Bernays.

Freud’s key teaching was that inside everyone, there were deep animalistic and irrational desires.

In the beginning of this documentary, we see how psychoanalysis’s sought to control these desires, as they believed this was necessary for peace – especially after witnessing the horrific brutalities of the second world war. They believed that their practice must be brought to the masses in order to create a perfect society. To businesses, this meant creating model consumers, and using Freudian thought in their marketing. To politicians and institutions of power, this justified the manufacturing of consent; shaping the truth so the public knows what to fear, and letting the elite few do what’s good for them.

However, a shift occurred in the mid 20th century. The discontent which Freud was aware of but believed was necessary was blown over by the 60s student movements, who rallied against the advertisements they believed were used to make them ambivalent to the atrocities the USA was committing in Vietnam. But this movement, having met the brutal force of the state, instead turned inwards to create a new self which would be free of the states control.

Capitalism stepped in to help these new individuals ‘be themselves’. Former radicals now had products catered to their values; they could buy products that they felt represented them and made them a unique individual. Consumers were no longer separated by class, but their psychological drives. These were done through focus groups, in which the participants were encouraged to talk irrationally and emotionally about the products, rather than examining the practicalities. This began the mass production of the independent self.

Businesses now no longer make what they believe consumers need, but respond to what consumers desire. Through the free market, people could be happy with themselves. So with this feeling of content, the public no longer saw a societal change necessary for improving their environment.

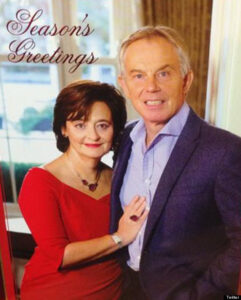

This shift was being replicated in politics too: first with conservatives such as Ronald Regan and Margret Thatcher, who promoted the market as an entity which would free the individual. In their wake, left leaning parties such as Labour began to focus on appealing to the swing voters, by making specific (and seemingly insignificant) policies based around their desires and values. People no longer felt exploited by the market, so these parties dropped their principals to protect people from industry. They were feeding back to the public what they already believed, rather than proposing solutions and ideas.

Politics, in the eye of a the new, isolated consumer, was a transaction. You pay the government in the form of taxes, and therefore expect a satisfactory product in return. Business had taught people to be individuals and act as individual consumers, we no longer see each other as a collective.

If a fifth episode was released today, Curtis would almost certainly explore the internet and our portable technology as a constant marketing focus group, which has atomised us even further as consumers. The role that cyber space plays in our new world and the further devolution of today’s post-truth politics are explored further in his 2016 documentary Hypernormalisation.