Aromas, scents and smells contribute to unique embodied experiences of place, distinct to a person and their spatio-social context (Gorman, 2017). This blog will explore how individuals can interpret the same smells differently and how smell walking/smell noting are a valuable method for understanding one’s personal olfactory experience of a city.

Smell plays a significant role in how we experience and perceive the places we inhabit (Tan, 2013). Despite its importance in placemaking, smell has been overlooked and neglected by urban scholars (Quercia et al, 2015). Smells impact not just our behaviour within a place, but the emotional and psychological meanings we associate with a particular site (Quercia et al, 2015). An individual’s emotional triggers and reactions to smells are impacted by the particular place, particular time and the individual’s background and context to the area in question (Xiao, Tait, and Kang, 2020).

We tend to judge smells by how familiar they are to us, we can observe insider/outsider perceptions of smells (Drobnick, 2006). Smells we recognise we tend to attach embodied meaning to, whether pleasant or unpleasant, while unfamiliar smells have no pre-conceived meanings. Thus the same smell can evoke different and surprising feelings and associations in different people (Drobnick, 2006). On a recent trip to Paris I wanted to see what effect being familiar with this city’s smells had an on a local Parisian friend’s responses to certain scents, and whether being an outsider meant my experience of these unfamiliar smells were different.

We embarked on a series of smellwalks over three days. I identified aromas and made smellnotes at specific locations. Notes included my own detailed descriptions of each smell, my own and my friend’s initial reactions and personal associations to each smell (McLean, 2014). Our differing responses became obvious as we travelled across the city and compared them. For example for my friend the familiar smell of Passy Metro Station made her feel nauseated when the brake metal smell was too potent and was associated with her early morning commute to University, evoking feelings of anxiety and stress. As an outsider not familiar with the smell of the Metro, I did not have a negative reaction. For me the smell was exciting, it reminded me of travel, exploration, and the anticipation of the upcoming adventure at my next stop.

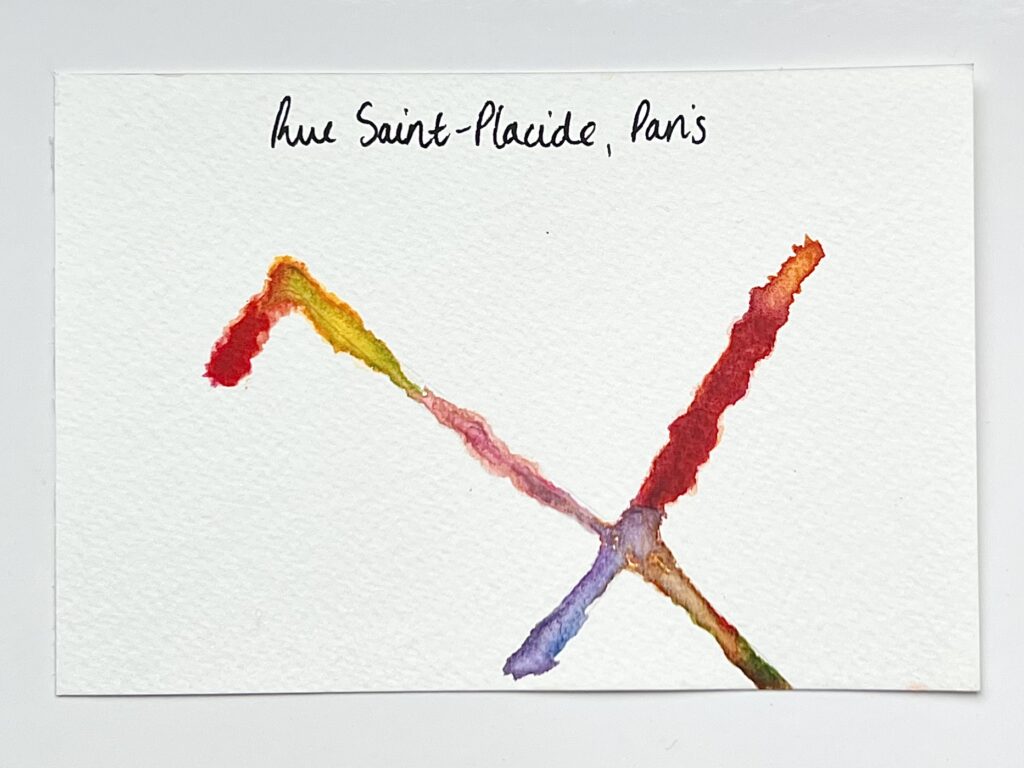

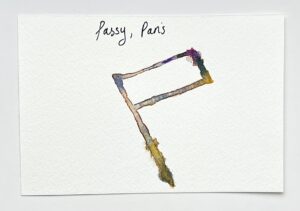

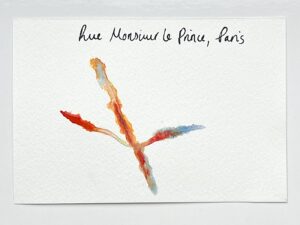

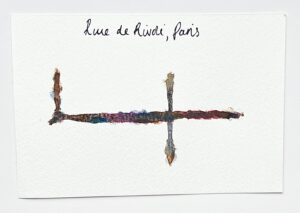

To better visualise and understand my smell responses I took inspiration from Kate McLean’s (2019) PhD thesis and created my own watercolour interpretations of my smellwalks and smellnotes. Each water colour representation is of a street or area that I visited and experienced specific smells. Underneath each watercolour are 6 descriptive words taken from my smellnotes that best describe the smells at each location.

Smellwalks can enable a researcher to capture unique narratives and stories that more traditional methodologies are unable to do (Allen, 2023). Undertaking smellwalks and making detailed smell notes enabled me to become “sensorially embodied” in my research as I was able to engage my nose in a “somatic mode of attention” (Allen, 2023, p.22). Focusing on actively sniffing my surrounding smellscape forced me to think about my immediate environment and the kinds of emotions evoked (McLean, 2013).

Word Count: 498

References:

Drobnick, J. ed., 2006. The smell culture reader (p. 342). Oxford: Berg.

McLean, K., 2013. Smell map narratives of place-Paris. New American Notes Online, 6.

McLean, K., 2014. Smellmap: Amsterdam-olfactory art & data visualisation. IEEE VIS 2014.

Tan, Q.H., 2013. Smell in the city: Smoking and olfactory politics. Urban Studies, 50(1), pp.55-71.