Darkness and light play an active role in establishing our relationship with home (Shaw, 2015). This blog will explore how sudden darkness can disrupt our sense of self and transform home into a place associated with fear and suspicion (Shaw, 2015).

The concept of home is complex, it is constantly being renegotiated and contested (Shaw, 2015). Dark and light attribute cultural values and meanings to place, and thus distinct spatial practices are produced in spaces of darkness (Edensor, 2015). Home is produced in the interplay of light and dark, it is not just a backdrop to which activity takes place, it is an active component of meaning making in the home (Shaw, 2015). The fear of the dark is persistent in western history, darkness has had negative connotations, while light has been seen as something positive that enlightens (Edensor, 2015). When emersed in darkness we are in what Welton (2013, p.6) refers to as a “social illumination” and having habituated to this, darkness can sometimes feel threatening (Edensor, 2015).

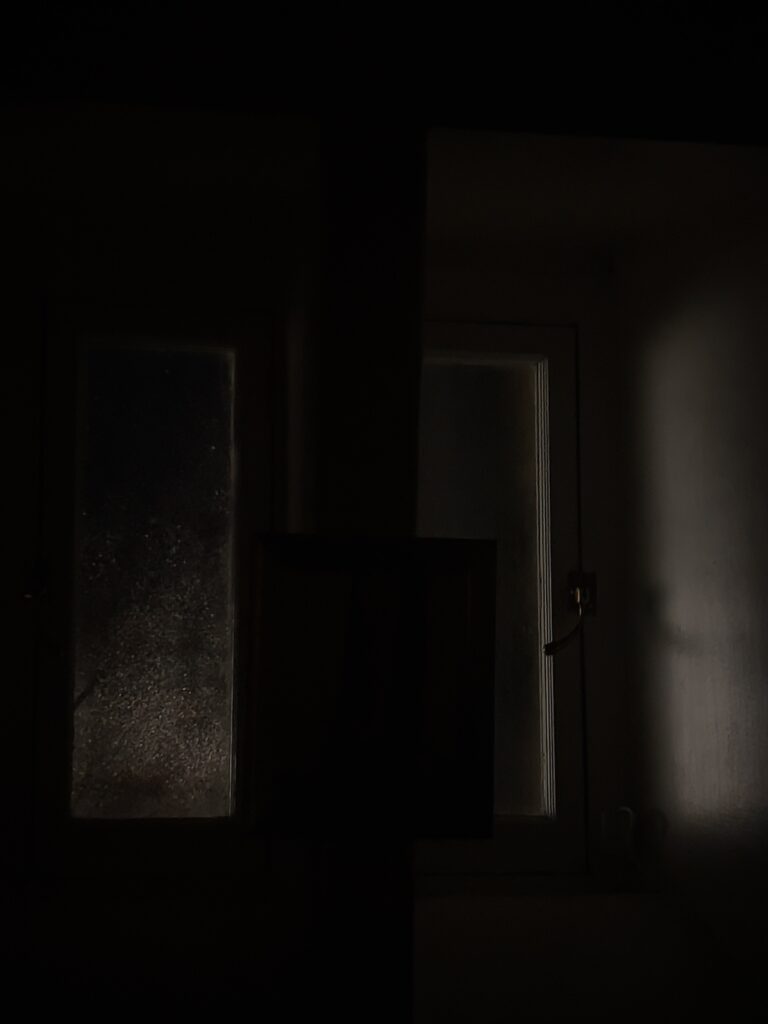

I was at home working alone when unexpectedly the electricity went out and I was plunged into darkness. I had no matches to bring light and no Wi-Fi to top up my electricity meter. I realised it would take 40 minutes of waiting in the gloom before light was restored. The flat went from feeling safe and relaxing to being unrecognisable and unfamiliar. I could no longer see my surroundings and began to feel insignificant in the space. The ways in which we understand and experience familiar and unfamiliar spaces is challenged by darkness (Edensor, 2015). This was my home, a space I had cultivated as my own, the space in which I identified my sense of self and was able to assert power and control over. Suddenly it felt very alien, I retreated to my bed, my ultimate sanctuary. I cocooned myself under my duvet for protection, I was on uncomfortable and on edge. As Valentine (1989, p.386) suggests, women have a” heightened consciousness” in the dark, adjusting their pace and movement in spaces they feel vulnerable because of the threat of perceived danger (Li et al, 2015; Shaw, 2015).

When engulfed in darkness, our reliance on the visual becomes irrelevant, instead we use other sense modalities in order to navigate the space we are in (Dunn, and Edensor, 2021). My eyes slowly adjusted and a distant hue of streetlights created creeping shadows on the walls. I became acutely aware of sounds echoing through the flat, the wind, distant voices, banging doors and footsteps. These once so familiar had now become loud and menacing.

When my flatmate returned, a sense of warmth and intimacy was restored. Her presence was comforting and the feeling of entrapment and emptiness dissipated. It was still dark but social contact had filled the void of isolation and lost intimacy and reinstated my sense of self in the home. The ways in which we encounter darkness and how we react and respond to it is thus also dependent on social context (Edensor, 2015).

In the home we are submerged in a protected bubble of light, familiar with our surroundings and thus our sense of self is evident (Shaw, 2015). We typically see home as a safe and secure space, but darkness can disrupt this and our internal and external worlds can become melded (Shaw, 2015).

Word Count: 509

References:

Dunn, N. and Edensor, T. eds., 2020. Rethinking Darkness: Cultures, Histories, Practices. Routledge.

Edensor, T., 2015. Introduction to geographies of darkness. cultural geographies, 22(4), pp.559-565.

Valentine, G., 1989. The geography of women’s fear. Area, pp.385-390.