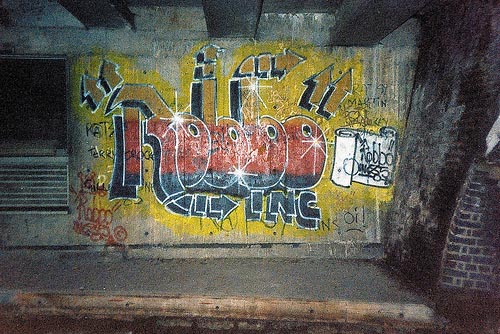

I want to show the way the narrative in the public and art establishment’s perception of graffiti street art has transitioned from the criminal labels of the 1980s, through the early 2000s, to today where such art is now respected as an art form, is seen as being of artistic and social value and can attract high-prices.

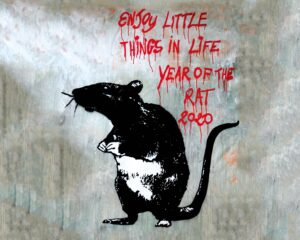

This transition is exemplified by Banksy’s fame, going from an illegal street tagger, in awe of the first generation of graffiti artists to being an internationally renowned artist and activist, whose works sell for millions. His emergence changed the narrative of street art, not just as an artform in itself, but how it is perceived by ordinary people and the way it is now used for various forms of political activism.

Banksy has however been a controversial figure within the graffiti art community for some time. As I touched upon in my previous blog post, Banksy’s reputation is tainted due to fact that he is seen to have violated some of the community’s fundamental ground rules. His stencilling work is seen by many as cheating, not freehand and thus not creative or risky enough. Even within stencilling he is accused of not being original, his work copied the technique of the Parisian Street artist Blek le Rat who was the first artist to use the black and white stencil style street art method that Banksy is now world famous for. He even adopted similar images to Bret, such as rats. He is also accused of becoming detached from the ethos of secrecy and personal risk by not even having his stencilled sprayed by him personally but by members of his ‘team’.

There was, and continues to be, a consequent backlash from the graffiti art community against Banksy which has led to feuds with other artists and the so-called ‘graffiti wars’. His feud with highly respected graffiti artists such as, King Robbo (see ‘Graffiti Wars’ documentary in previous blog) which came to a head when Banksy stencilled over King Robbo’s final work before he died, which was underneath the British Transport Police quarters and was the oldest piece of graffiti in London. This led in turn to a series of tit for tat defacements. In provoking this feud Banksy had broken a sacred rule of the graffiti art community which is to never paint over or deface another artist’s work.

Such incidents have isolated Banksy even more and estranged him from the roots and fabric of the community that shaped him and made him famous. In spite of these problems Banksy’s work has become very popular and is celebrated by the public who are generally oblivious to these undercurrents, and he has become the iconic, acceptable face of graffiti art globally.

Final Outcome

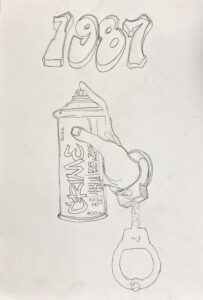

In my final piece I wanted to illustrate this transformation of illegality to acceptance but also to expose some of the underlying Banksy controversy. I chose a bold graphic style drawing, not dissimilar to graffiti art itself, and incorporated blockbuster graffiti style text and numbering. The work consists of two drawings that sit alongside each other. The first represents the early narrative of graffiti art, one of risk, crime, illegality and disorder. The second represents the contemporary popular accepted status of the artform, and of its best known representative Banksy. The spray can, the primary tool of the graffiti artist, is the common element and unchanged except for the label. ‘CRIME’ on the first can is how graffiti art was seen, and thus labelled, in the 1980’s. Whereas by 2022 it is ‘BANSKY’ himself that has become a ‘brand’ and thus the label on the second can. The 1987 drawing has handcuffs hanging from the arm of the artist while the 2022 artist (i.e. Banksy) is free from such shackles and instead has Pound sign tattoos on his arm reflecting the commoditisation and high values now placed on Banksy’s and some other graffiti artist’s work.

I entitled this piece ‘From Bite to Bucks’. In graffiti terms ‘bite’ refers to stealing someone’s art, ideas, names, tags, letter styles or palette. ‘Bucks’ refers to money, being the American slang word for dollars, and represents in this case the ability to generate wealth. It also helps link the piece to the American origins of graffiti art. The transition of the narrative thus comes full circle and is complete.