The narrative of graffiti art has changed remarkably from the hip hop, acid house, train bombin era of the late 1980s. With the emergence and general public acceptance of certain street art icons questions have been raised over the last few decades over what now constitutes ‘street art’ and what is still regarded as criminal vandalism. While a growing number of talented artists have arisen, probably the most famous, or infamous depending on your point of view, to date is the now world-renowned street artist Banksy.

Banksy, more than any other street artist, has benefited from what can only be described as a transformation in the perception of this artform. Having made some of the world’s most controversial and celebrated works since the late 1990s, the platform Banksy has created for societal and political expression, and the attention he has brought not only to the discipline of street art as a whole but also to other artists has had a profound impact both on the subculture of graffiti art and the art establishment.

For some years now Banksy has had control over his own narrative. While his effective anonymity helped him evade detection and succeed in the early days, his legacy and status means he is now virtually untouchable. Even if his identity were now to be revealed, he would not be arrested. His works are handled and treated in an entirely different manner to other graffiti artists. Questions of criminal damage and illegality are no longer an issue for Banksy’s work. Instead the appearance of a new Banksy work is usually prized by the recipient, celebrated and commented on by the press and art world, and is seen as being valuable in itself, adding value not only to the property but also to the locality which can benefit from the association. It is no longer seen as damage or an offensive blight on the environment. The only downside now is the burden of protecting the work and the hordes of people coming to take photographs of it.

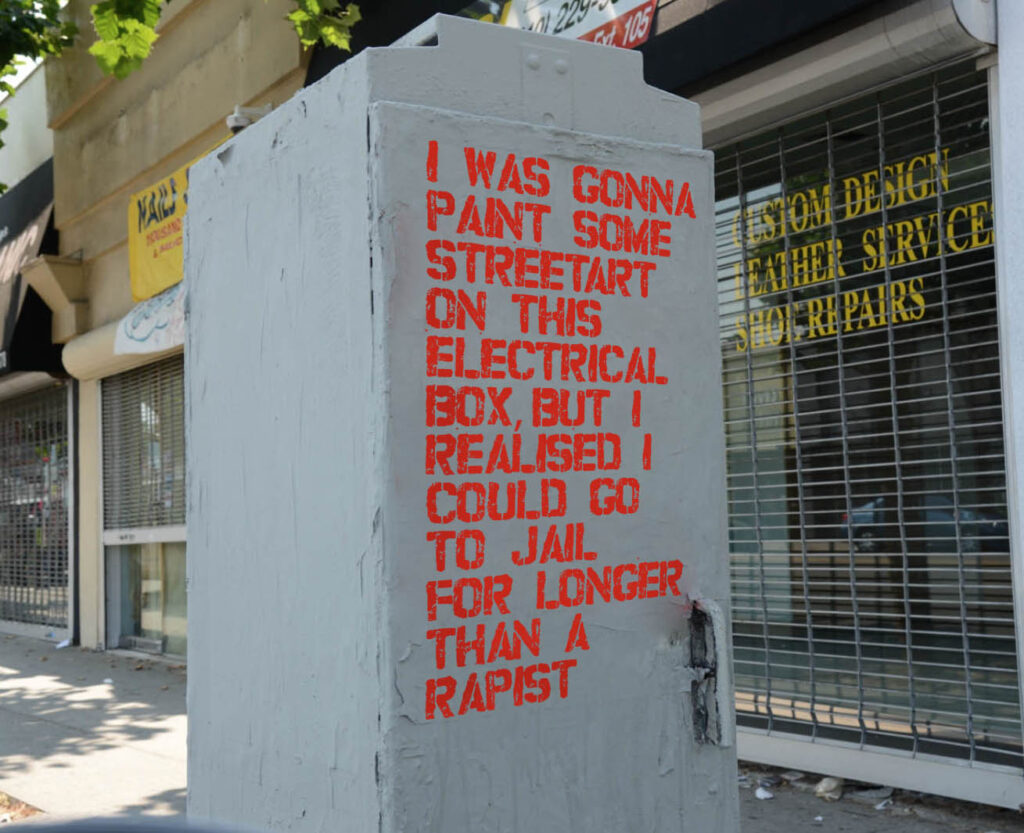

Nonetheless, however differently the public may view some street art there is no legal distinction between street art that is seen as having ‘artistic’ or social merit, that has been secretly but thoughtfully created on a site, and other forms such as graffiti tagging, the spraying of a “tagger’s” name or symbol on urban street surfaces, some of which can be seen as ‘artistic’ and others less so. Such Tagging is often viewed by many people as aggressive antisocial defacement of property and of little worth. All forms of graffiti art are still illegal unless commissioned or consented to in advance by the property owner regardless of the potential artistic appeal and intended message, the artist risks criminal prosecution. However, if, the work appearing on a wall is confirmed as a Banksy, in most countries around the world he would now escape any potential legal consequences even if he were caught in the act. He is thus an extreme case of this inconsistency of treatment. The irony now is that when his artworks are created, due to their perceived artistic and monetary value, they are often immediately protected by the authorities from other potential ‘vandals’ from within his own graffiti art community! This distinction is what has allowed a real sense of unfairness and inequity to arise within the subculture.

In the 2011 Channel 4 documentary ‘Graffiti Wars’, we see that opinion within the graffiti community on Banksy was clearly divided. To the public, celebrities, the art establishment and even by the law, Banksy is heralded as a great modern art revolutionary and is revered for his political activism. However, among street artists themselves, his exalted status is questioned. Banksy is seen as privileged, his work doesn’t receive the same level of legal scrutiny, consent requirements or consequences as other, even well known, street artists. His work isn’t threatened with removal and he himself is protected by his guarded anonymity and by what has come to be viewed as the Banksy ‘brand’. Whether it is stencils on public property or privately owned homes, Banksy is able to ignore basic legal questions such as permission and his work is automatically treated as legitimate in a way no other artist’s is. A quote from a graffiti artist in ‘Graffiti wars’, “When street artists do it, it’s vandalism,” “When Banksy does it, it’s an art piece. There’s a disconnect there.”

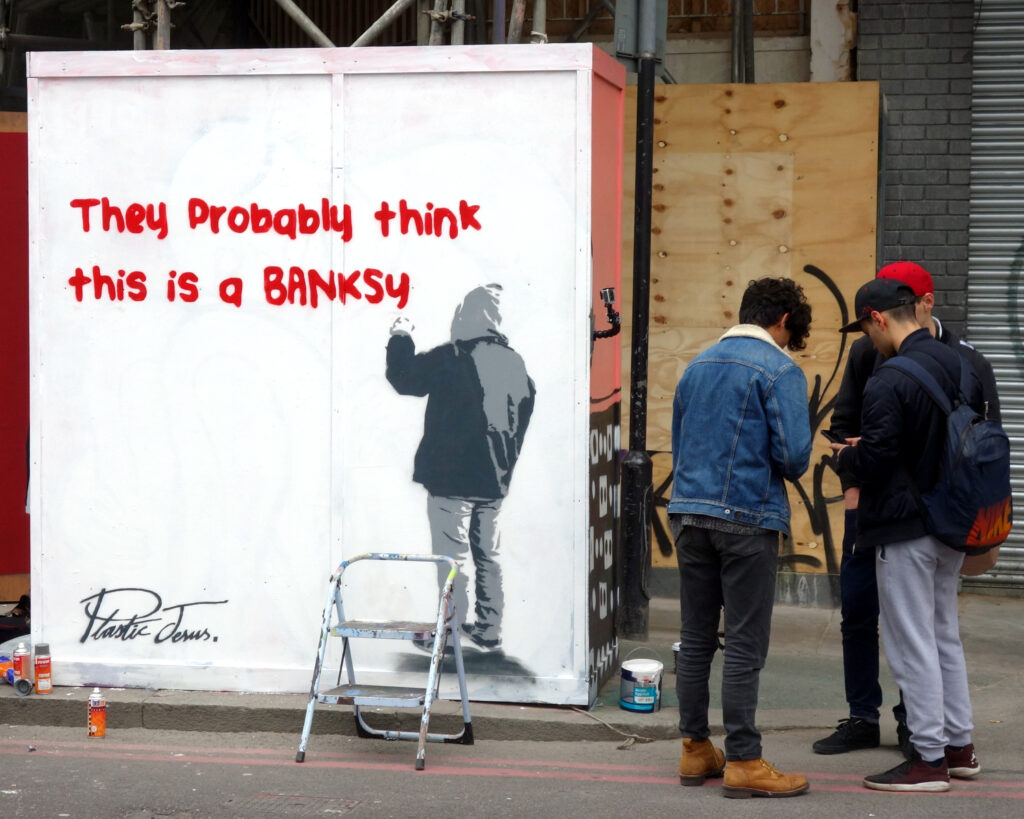

‘Plastic Jesus’, another anonymous UK born street artist, has created some of LA’s most prominent street art murals and, much like Banksy himself, is famous in the industry for ironic and often provocative installations. As can be seen in the images of his work below he has shed light on just how dissimilar Banksy is treated to other street artists. Bansky thus remains a controversial figure in the graffiti art community to this day.