Collective Gallery Field Notes

The Collective Gallery in the City Observatory Calton Hill, Edinburgh

18 January 2022

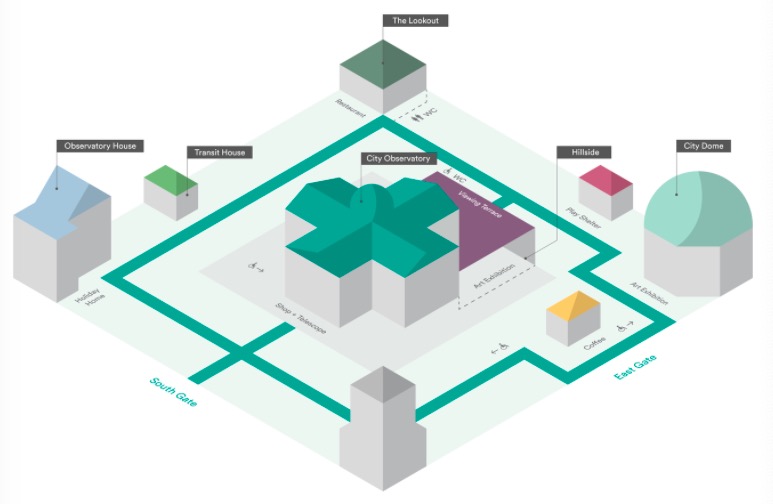

Yesterday, I visited the Collective Gallery. It is a centre for contemporary art in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was founded in 1984 and had been supporting new work by artists. The Collective aims to find interrelationships between artists, practising curators and the people who live and work in the area. I could see that the Collective’s programme of exhibitions and events showcased the diversity of contemporary art. Through the website, I found projects where their work allows artists to meet and collaborate with different local community members to create together.

This term I have been studying the interdisciplinary integration of contemporary art and anthropology, using a different approach to previous years – putting curiosity, focus and learning through ‘fieldwork’ experiences at the centre. With regard to the collective gallery, my assignments have been informed not only by reading and discussion but also by observation and note-taking.

For this week’s assignment, ‘Collective Gallery’ I wanted to focus on observation, anthropology and art – I felt that observation would allow for a better understanding of history and the positioning of the new Collective Art Gallery. After that, in terms of which parts of the exhibition the audience is interested in, their interaction and reaction to the contemporary artworks. And in what spatial order the artworks are assembled and arranged, and what connections exist between the exhibits and the subject matter. Hal Foster’s article ‘The artist as ethnographer’ (1995). In other words, the artist is also an ethnographer. The motivations, meanings and values of the artist in relation to the community and audience are linked to the artwork through which they are made.

For example, I became aware of contemporary artists creating projects of anthropological insight and artistic projects that emerged as a result of ethnographic research. For example, ‘Nothing About Us Without Us’ is a long-term collaboration launched in 2016 by the Collective Gallery and led by Swedish artist and filmmaker Petra Bauer and the Scottish sex worker organisation ‘SCOT-PEP ‘. The group shared their daily experiences of work, political organisation and the structural challenges they face when trying to change the conditions of sex workers in Scotland. Watching films together and actually testing different performance strategies has been central to the project. I have seen them constantly listening and sharing ideas about these processes and asking questions.

In addition, I saw Cauleen Smith’s first solo exhibition in Scotland. h-E-L-L-O (2014), a short film that signals a search for connection in a time of uncertainty and unrest for sites around post-hurricane Katrina New Orleans. I have noticed that the art project is presented as a form of ethnographic research. The artist focuses on using and adapting elements found in anthropological methods and practices to create contemporary works. These works are alternately subversive, suggestive and fascinating. Subsequently, contemporary art and curators produce the results, and, at best, the exhibition turns to anthropology. Smith employs film, music, and performance to explore the intersection between fact and fiction. Today’s artists have fused different approaches to the art of storytelling. I found that it is a way of making sense of the world by relating or rather “telling” observations and theoretically re-telling stories that researchers encounter during their fieldwork. This is not a new development in ethnography, what is new however, are the modes of telling that have come to include not only innovative ways of knowledge production which in turn keeps modifying the various modes of ethnographic storytelling.

In terms of Factish Field, the Factish Field symposium explored ideas of art-ethnography. An invited panel of artists and anthropologists presented their ideas on art and ethnography and how they apply this to their own practice. I noticed that Factish Field took its starting point from the French anthropologist Bruno Latour’s concept of the ‘factish’, a combination of fact and fetish as a way of thinking about the relationship between facts and beliefs. 在Angela In McClanahan’s essay, I became aware of artists and anthropologists focusing on practice-led research to revisit the ethnographic shifts in contemporary art. Throughout the week, both artists and anthropologists will be paired for a series of in conversation events, and will develop workshops in which the group will consider some of the ‘big’ questions surrounding both anthropological and art practices, where they intersect and diverge, and the potentially creative, generative serendipities that might be found in the margins that exist between the two disciplines. Topics include:

Where does it play out? In the field, studio, gallery, academia?

How can artists and anthropologists share research methodologies?

Where are the links between theory and practice?

Who is the audience? And how is it distributed?

Who makes the rules and how are they imposed or regulated? Is it important that they are?

I have found that ethnography is approached from a thematic and methodological perspective, rather than defining ‘ethnographic art’ by looking for fixed categories. It does so by focusing specifically on artistic practices and processes. I became aware of the artists’ use of film and art-related practices and, in a speculative way, brought together ideas shared by participants during summer school. By considering why the study of art and anthropology is now particularly relevant, it offers ideas about how art and anthropology might potentially work together in the future.

I realised that the ‘Factish Field’ project itself could only touch on the most basic principles of anthropology and the potential areas of interaction that drive continued growth, which most participants shared. Neil notes that the dissonance and common ground between art and anthropology create the basis for ‘interdisciplinarity’.

Contemporary art and anthropology are thus both products of modernity and modernism. As ‘Factish Field’ focuses on, one of its aims is to commission new work that establishes a common approach and worldview between anthropology and art in an overt way. Another project commissions public engagement with the theme of urbanised development. Both often through their own ways of practice, but increasingly in a common space, generate ‘chemistry’ with each other. Although, the contexts in which these occur are diverse and varied, the ‘Factish Field’ project provides a productive model on which to base these works, which provoke a variety of discussions and new work/generate new discourses around these and other themes.