After reading the ‘How to earn your skeptic badge’ article by Harry Jenkins (Jenkins 2012), I was glad to know that I’m not the only one who is skeptical about digital badges. I was in total agreement with Halavais that digital badges appear to be ‘little more than a visual conceit’ (Halavais 2012). However, after a thorough consideration of ‘A Genealogy of Badges’ (Halavais 2012) and a careful contemplation of my early experiences of badges and I was able to understand the origins of my skepticism.

As a child, I was a badge-hungry member of the 14th Halifax Brownies. I coveted the full arm of badges that some older girls possessed, but despite my frequent badgering (absolutely no pun intended) of Brown Owl, we seldom did any badge worthy tasks. I was disgruntled with my pitiful collection of badges and it was definitely a contributing factor to my final departure from the troop.

When I tried to locate the Brownie badges within either the ‘guardian moral syndrome’ or the ‘commercial moral syndrome’, (Halavais 2012) I experienced some conflict. I would say that the values of the Brownies and goals of their badge system are aligned with the ethics of the commercial system; Be industrious, thrifty, productive, efficient, competitive and collaborative.

However, if I’m honest, I was drawn to the glory of the badges; the ‘prowess, discipline and fortitude’(Halavais 2012), values most definitely aligned with the guardian class. I don’t recall any enthusiasm on my part to learn new skills that would have earned me a badge, it was prestige of accomplishment that fuelled my desire. As an eight year old and the youngest member of an extremely competitive family, it is not surprising that I longed for status and power.

When I first read ‘A Genealogy of Badges’ I struggled to understand what was so ‘monstrous’ about the moral hybrids that are created when learning badges support ethical expectations from both the guardian and commercial systems. By reflecting on my desire to earn prestige through Brownie badges, I was able to understand how the badge, (as an artefact), inherits guardian values and how the awarding of such a badge motivates individuals extrinsically and belongs to the stewardship style of governance (Halavais 2012). This is at odds with the values of autonomous, self-directing, life-long learning that digital learning badges, particularly in the ‘open’ learning movement, are trying to promote. The use of learning ‘badges’ could be said to confuse the ‘emergent’ governance of the individual.

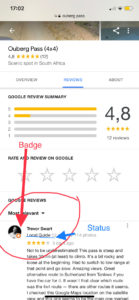

Due to time constraints I didn’t manage to earn a digital learning badge. The digital badges that I have earned through the Audible app and the Apple Activity app really didn’t inspire further analysis. One digital badge system that did interest me was the Google Local Guides. Google awards points for contributors who post reviews, photos and ratings to Google Maps. Contributors are awarded badges and ‘local guide’ status according to the number of points they accumulate.

This photo, published with the kind permission of the Local Guide, shows how the badge and the status are displayed adjacent to the review. The points program is designed to reward people that contribute content; written reviews (200+ characters = double points), photos, videos, new places and roads. It also encourages interactions with other contributors; answering questions and fact checking. The program promotes a form of ‘emergent’ governance (Halavais 2012) ; users creating and, to some extent, managing content. It appears to be aligned with the values of the commercial class; collaborating easily with strangers, promoting convenience, being industrious.

The Google points system rewards frequency and quantity of contribution, it does not recognise the quality of a contribution or even a peer rated ‘helpfulness’ of a contribution. However, the status of ‘Local Guide’ and the badges which are awarded could be construed as a mark of quality. The bearer could be seen as an authority, traditionally a local guide would be someone who has local (specialised) knowledge of a region. In this sense, there are values of the guardian class to which the program also aligns; exert prowess and respect hierarchy (of knowledge).

Halavais states that badges can be ‘a clear way to express what is valued by a community’ (Halavais 2012). If the Google Maps community value local (specialised) knowledge, it could be argued that the badges are communicating those values despite the fact that the point system does not reinforce those values at all. The Google Local Guide system seems to exemplify the conflict that arises at ‘the intersection of the two moral codes’, a characteristic outcome of the social web or ‘web 2.0’ (Halavais 2012). Google are promoting new ways to collaborate and create online content; ’emergent governance’ whilst simultaneously (and somewhat deceptively) holding on to the hierarchical values of ‘stewardship governance’ in their badge system.

It would seem that despite all their ‘disruptive’ innovation Google is still catering to the little power-hungry Brownie that lives in each of us.

Halavais, Alexander M. C. 2012. “A GENEALOGY OF BADGES.” Information, Communication & Society. https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/1369118X.2011.641992.

Jenkins, Henry. 2012. “How to Earn Your Skeptic ‘Badge.’” Henry Jenkins. Henry Jenkins. March 4, 2012. http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2012/03/how_to_earn_your_skeptic_badge.html.