For the creation of Joey Simons and Keira McLean’s wall montage as well as for the development of the curatorial framework of the Living Archive, we engaged with practices of community archiving. These include grassroots activities of creating, collecting, curating, preserving and making accessible collections focusing on a particular community or specified subject (Flinn, 2007).

Community archives are set apart from traditional ones by the importance of the self-definition and self-identification of a community or a group in its own archival processes (Flinn & Stevens, 2009). Members of a given community take a leading role in recording their own history as they decide which narratives are valuable to them and thus what is worth preserving and remembering. Furthermore, community archives are also recognisable as they often collect materials that don’t conform to traditional notions of what a record or an archive is (Flinn & Stevens, 2009).

The term ‘community’ is a contested one, as scholars like Terracciano (2006) discuss how it is often used as a reductive euphemism to refer to groups facing social exclusion, or ethnic and faith minorities. In cultural practices, a key issue is that “community” has become an umbrella term in outreach endeavours to refer to anyone who doesn’t engage with institutionalised culture (and sits outside of a white, middle-class normative audience) as a homogeneous and monolithic entity. The lack of specificity in the definition of the term “community” has also consequences in cultural practices as its biases lead programmes to adopt a “copy and paste approach to all marginalised communities” (Cunningham & Mui, 2022). A monolithic definition of “community” should be challenged in theory and practices. In fact, if all individuals are treated as one homogeneous entity, whose traits are often informed by generalisations, this will only result in an increased stigma that will solidify rather than alleviate marginalisation (Cunningham & Mui, 2022).

Bearing in mind these debates, communities can be defined as groups of individuals brought together by locality, ethnicity, faith, sexuality, occupation or ideology and a combination of the above (Flinn & Stevenson, 2009). In recent UK archival practices, community archives have tended to focus especially on minority social and ethnic groups (Bastian et al., 2009).

In our curatorial project, I encountered some examples of community archives. One of which is Glasgow Women’s Library: a gender-minority-led organisation which collects, preserves, and exhibits materials about women’s experiences (Glasgow Women’s Library, n.d.).

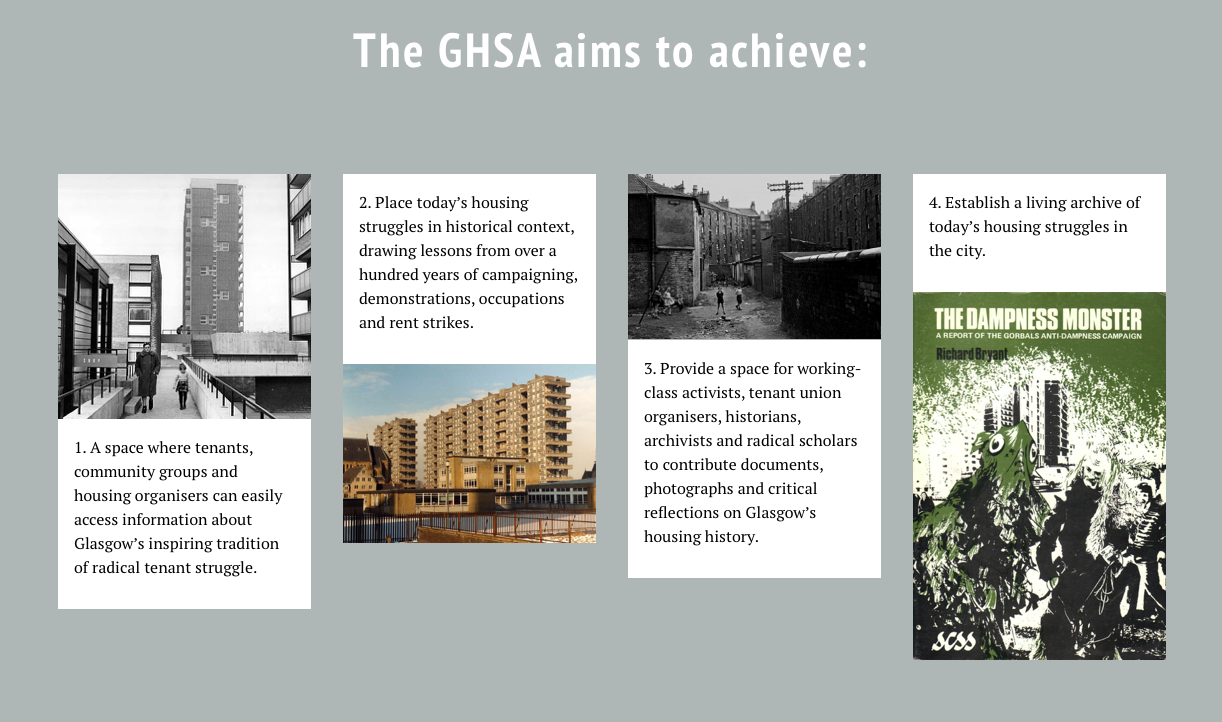

Another example is the Glasgow Housing Struggle Archive (GHSA): a project aimed at “recording, sharing and discussing the past and present of working-class organising for decent housing in [the] city” (Glasgow Housing Struggle Archive, n.d.) It is led by a collective body of tenants with experiences of housing struggles, and it welcomes public submissions through a living archive to continuously expand the record (Glasgow Housing Struggle Archive, n.d.). GHSA can be considered a community archive as it involves individuals who self-identify as working-class in the creation of a record that captures their experiences of organising for better housing.

My interest in community archives lays in the opportunities they offer as spaces of resistance for identity and community formation. In fact, they allow historically subordinated groups to recover, preserve and ‘recast’ the stories of a community from their own perspective (Flinn & Stevens, 2009). This allows community archives to challenge the distortions and omissions of mainstream historical narratives and of heritage collections that sustain them (Hall, 2005).

Examples of how community archives can be used to ‘recast’ stories can be found in Joey Simons and Keira McLean’s Glasgow Housing Struggle Timeline (2021). This montage tracking women’s contribution to fairer housing from 1915 to the present day reclaimed the fundamental role historically played by women in achieving housing rights, often omitted from official records (Gausden et al., 2021). The recovery of these narratives recasts the identity of historical individuals and presents how community archives can function as tools of identity creation as they develop alternative and more complex narratives about marginalised groups’ experiences (Ketelaar, 2005).

Community archives can also support community formation as they strengthen and reinforce the communal identity of a group by making its memory visible and shared (Josipovici, 1998). According to Bastian et al. (2009), in fact, the ability of a community to conceptualize itself (identity formation) also depends on its capacity for remembrance and to express that remembrance communally. The display of archival materials- through exhibition-making or online websites- is one way to achieve what Bastian et al. (2009) envisioned as communal remembrance. This can be understood as the “social transmission of memory which supports the building of community and of identity” (Sabiescu 2020). An example is A Century of Housing Struggle (1915-2016) part of GSHA: an online timeline with photos and information which tracks the history of Glaswegian housing struggles from a working-class perspective (Glasgow Housing Struggle Archive, n.d.). This timeline, as the display of other community archival materials, allows individuals to find connections between their own past experiences and those of their community creating a bond between people and across generations (Bastian et al. 2009). By mediating a common past, community archives can therefore shape a sense of community, continuity and cohesion to form a collective identity (Ketelaar, 2005; Sabiescu, 2020).

Furthermore, community archives can support an agenda of education for social change. According to Hall (2001), the creation of archives is an act of resistance. In the collection, creation, and ownership of resources that correct and re-balance omitted narratives, community archives are seen as counter-hegemonic tools for education and weapon in the struggle against discrimination and injustice (Alleyne, 2007). In fact, they can present an alternative way of understanding the current development and functioning of society (Gilroy, 1995) to inform present and future actions of resistance (Flinn & Stevens, 2009). Moreover, as the display of archival records links the historical struggles to contemporary ones, community archives have the potential to inspire community resistance in the present too (Flinn & Stevens, 2009).

Community archival practices offer us a useful framework to inform our approach to the curation of the Travelling Gallery. By including community archival records in the exhibit we hope to gather corrective narratives about housing issues, foster community and identity formation in the different locations we will visit and support an agenda of community resistance and social change.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alleyne, B. (2007) Obituary: John La Rose (1927– 2006), History Workshop , 64 ,

Bastian, J. A. et al. (2009) Community archives the shaping of memory / [compiled by] Jeannette A. Bastian and Ben Alexander. London: Facet.

Cunningham M., Mui T. (2022) Working Better Together- Creative Community Hubs Project Report. Edinburgh: Out of the Blueprint, 2022. Available at https://issuu.com/whalearts/docs/working_better_together_25_05

Flinn, A. (2007) Community Histories, Community Archives: some opportunities and challenges, Journal of the Society of Archivists , 28 (2), 151– 76.

Flinn, A. & Stevens, M. (2009) ‘“It is noh mistri, wi mekin histri.” Telling our own story: independent and community archives in the UK, challenging and subverting the mainstream’, in Community Archives. [Online]. pp. 3–28.

Gausden, C., Lloyd K. Spencer C. and Raha N. (2021) Life Support- Forms of Care in Art Activism-Exhibition guide. Glasgow: Glasgow Women’s Library.

Gilroy, P. (1995) There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack , Routledge.

Glasgow Women’s Library (n.d.) About Us. Available at https://womenslibrary.org.uk/about-us/our-values/ Accessed 10.04.2023

Glasgow Housing Struggle Archive (n.d.) A Century of Housing Struggle (1915-2016). Available at https://glasgowtenantsarchive.com/about/ Accessed 10.04.2023

Hall, S. (2001) Constituting an Archive, Third Text , 54 , 89– 92.

Hall, S. (2005) Whose Heritage? Un-settling ‘The Heritage’, re-imagining the postnation. In Littler, J. and Naidoo, R. (eds), The Politics of Heritage: the legacies of ‘race’ ,Routledge

Josipovici, G. (1998) Rethinking Memory: too much/too little, Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought , 47 (2),

Ketelaar E. (2005) Sharing: Collected Memories in Communities of Records. Tijdschrift Voor Nederlandse Taal-en Letterkunde. [Online]

Sabiescu, A. G. (2020) Living Archives and The Social Transmission of Memory (New York, N.Y.). [Online] 63 (4), 497–510.