Mirrors blur the line between reality and image, showing ourselves our surface double so that we may reflect on ourselves in 3D. Windows are boundaries which separate interior and exterior but also connect them; they can be opened to let the outside in, and the inside out. Crucially they are transparent mediums allowing us to see through to a scene or an event that otherwise would have been obscured from us. A strange way to start a blog about Mrs Dalloway, but I think we can understand the structural framework, formal elements and thematic concerns of the novel by approaching it as a narrative that offers readers a series of windows and mirrors. Firstly, I read Clarissa and Septimus as structural doubles who mirror each other throughout the novel. Yet intense focalisation and free indirect discourse means that these characters also function to blur the boundaries between interiority and exteriority, past and present, private and public, life and death. In this sense they can also be read as windows of transparency, used by Woolf to provide insight into the obscurity of inner psychic states and hidden realities, but more than this, they are also mirrors reflecting the ways in which societies and communities impinge upon the private lives and minds of individuals.

As a starting point, I read the phrase, ‘What a lark! What a plunge!’ (3) to encapsulate the way in which the novel traces the narrative trajectories of Septimus and Clarissa in parallel to one another. Clarissa plunges into life, connecting those around her through the joyous ‘lark’ of party-giving whilst Septimus plunges to his death so that Clarissa may live. Certainly if read in line with a Freudian tripartite model of the mind, we may see Clarissa rising to the surface of the super-ego, occasionally lapsing into the ego in private moments whilst Septimus plunges deep beneath the surface, to see the ‘id’, the entrenched darkness that lies beneath. It is significant then that Septimus commits suicide via a window:

‘“I’ll give it you!” he cried, and flung himself vigorously, violently down on to Mrs. Filmer’s area railings’ (108)

I suggest the shattering of the window takes on symbolic power as a transparent unveiling and shattering through to reveal not only the negative effect power systems have on individual psychic states but the fact that our notions of sanity are fabricated, in need of breaking if one wishes to have any authentic freedom. Yet I also suggest that Clarissa’s moments of staring through windows offer similarly poignant and existential insights in the novel. Take for example the bookshop scene:

‘But what was she dreaming when she looked into Hatchard’s shop window. What was she try to recover. What image of white dawn in the country, as she read in the book wide open: Fear no more the heat o’ the sun/Nor the furious winter’s rages’ (7)

The reference to mortality through Shakespeare’s ‘Cymbeline’ indicates that windows offer depth in this novel, and in this case expose the deeper understanding of our connection to death. The window becomes a blurred boundary between the quote of death and the vitality of the urban street. What is also highlighted here is the mental agony of losing memory and losing with it a sense of one’s self and one’s past which parallels to Septimus’ sense of grief and loss following the death of his partner at war. The fact that Septimus is described as having ‘waved his hands and cried out that he knew the truth! He knew everything! (35) suggests that like Conrad’s Marlow who sees ‘the horror, the horror’, Septimus is a man driven ‘mad’ because he sees too deeply into human nature and the fabrication of the world around him. Yet Clarissa’s staring through the window to the old lady opposite her house suggests she has a similar depth of insight into her own loneliness, mortality and age. And yet after Septimus’ death this shifts:

‘It was fascinating to watch her, moving about, that old lady….. to watch that old woman, quietly going to bed alone. She pulled the blind now… The young man had killed himself… she must go back…. she must assemble’ (135)

Septimus’ confrontation of death through a window means that the blind is closed on Clarissa’s nihilism so that she may go back to her party and continue to create. Yeats’ quote: ‘dying eachothers life, living each other’s death’ (W.B Yeats) comes to mind in highlighting how the whole novel gears towards exploring those dialectics of life and death, annihilation and creation. There is thus a sense that Septimus’ death creates the window, the mirror and the transparency necessary for Clarissa’s own self-actualisation because by living Septimus’ death (‘she felt somehow very like him’ 135) she finds her purpose. This then allows her to move from living the nullifying role of ‘Mrs Dalloway’ (1) at the novel’s start to being authentically, Clarissa, at the novel’s close as Peter Walsh declares ‘It is Clarissa. There she was’ (133).

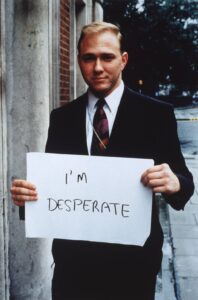

The quote at the novel’s beginning: ‘She had burst open the French windows and plunged at Bourton into the open air’ (3) thus takes on new significance by the novel’s end. Firstly by opening the windows, she opens her private self up to the world at large. Yet this opening of windows can be read on a deeper symbolic level in that her bringing together of figures from the pastoral idyll of the past into the urban present of her London home ruptures the boundaries between urban and rural, the past and the present, interior and exterior in the same way that a window is a boundary point that connects inside and out. In many ways the novel makes me think of Gillian Wearing’s exhibition that gave subjects the power to represent their own realities against how they may appear to others. In the image below there is a surprising contrast between how the man looks (the role he plays as a businessman) and how the sign reveals a sense of his inner turmoil that would otherwise be unseen. I think the focalised insight we get into the private minds of Clarissa and Septimus thus functions to resist the ways Foucauldian systems of power tend towards fixing individuals or essentialising subjectivity. Jacob Littleton’s article that reads Clarissa as an artist who ‘transmutes her private experience into a public act’ (36) is thus a delicate reading of Mrs Dalloway and a convincing one, but I’d push it further to suggest that in some ways Septimus is also an artist but an artist perhaps more akin to the likes of Nietzsche who Felman reads as ‘going mad in our place’ (11). Septimus is an artist whose destruction facilitates creation – ‘he plunges with his treasure’ (the truth) (134) – so that Clarissa may stay sane and create. Clarissa on the other hand is an artist whose very creative act of party throwing destroys conventions which deny such an act as artistry and which would otherwise attempt to deny her the power she gains through this creative act. Both defy those who try to limit them.

‘I’m desperate’ 1992-3 Gillian Wearing

I’d also point to the exhibition WeltenLinie (2017) by Alicja Kwade which has been described as ‘a bewitching setup of black frames, some containing highly-polished mirrors and other not’. Effectively the idea is that you either see yourself in mirrors or you see through the window-like-space within the frame in order to see others. Mrs Dalloway with its concerns of transparency, connectivity and the exposing of interior states, could therefore be read as a narrative embodiment of Kwade’s exhibition of windows and mirrors. Free indirect discourse and multifocalised narrative offers multiple windows into the private minds of a public collective. Each mind gets ‘A Room of One’s Own’ in the house of the novel, so to speak (lol a lame pun but had to be done). Yet it is also a book of mirrors in the sense that Clarissa and Septimus internally function as interconnected doubles mirroring each other but also mirroring back to us, as readers, aspects of our own humanity and our own conscious experience of the world. Clarissa, I argue, as the most complex and nuanced character in the book, may be read as a mirror of our divided selves (to borrow R.D. Laing’s term) and the ways in which we project public versions of ourselves that may differ from the darker selves we return to in private. Against Ho’s claim Mrs Dalloway is ‘certainly no realist novel’ (Ho 64) , I argue that the text is a profound and realistic depiction of the ways in which our sense of self stems from interior and exterior processes of construction. It is a realism of the unreal, that makes tangible and readable the intangible and unreadable aspects of our minds.

WeltenLinie (2017) by Alicja Kwade

Not really part of the analysis but just a little bit of song to ‘lighten’ the mood even though it’s pretty semi-emo-folk-miserable:

I think a really useful summary of my general reading is reflected in Holly Humberstone’s song Thursday. I’m pretty certain it isn’t informed by a reading of Woolf (though who knows) but other than being a lovely song, the chorus captures a sense of the novel and its representation of mental health, madness and the public/private dimensions of the self:

And I was kinda hoping

You were kind of broken too

How on earth, how on earth do you hold it together?

Doesn’t it mess you up a bit?

Doesn’t it hurt?

Let it burn, this is hell on earth and you’re enjoying the weather

One for the team, I’ll take the hit, do your worst

There is a brokenness in Clarissa Dalloway; the many allusions to her ill health support this, but she holds it all together, as an artist does, arising from the darker realisation of her own mortality to the act of ‘Being’ and connecting others. Perhaps this has something to say about how exhausting art can be; to have such insight into what we are and to hold all that complexity together in a vision….

Yet even within the novel there is a sense that ‘holding it together’ is itself a damaging fabrication imposed by norms that dictate what sanity should look like. In this sense Septimus exposes how we can simply let go of that superficial self, letting it ‘burn’. It is thus quite intriguing that Septimus is associated with flame imagery throughout the novel and yet, enjoys nature and sees its interconnectedness without making it an object. This burning of social convention and insight into nature makes him an oppositional figure to Bradshaw who attempts to objectify Septimus in order to assert himself as dominant. Finally, it is certainly true that Septimus is a character who takes the hit, and who plunges to his death through the window so that Clarissa may thrive, and so that the female artist may triumph.

Song: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MldnKK__vHg

Recent comments