Week 2 – Narrative as an Evolving Dynamic

This semester’s first intensive was ‘World as Story’ which covered a range of disciplines from politics and anthropology to economic history. We began the first day with a discussion on narrative, which was encapsulated into the following points:

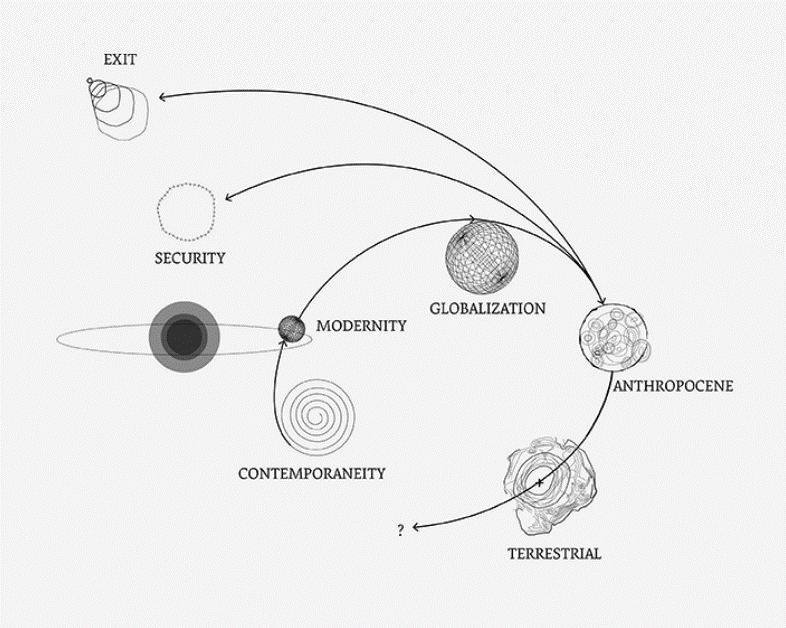

- A narrative tells us what could happen. It’s not static but dynamic. It isn’t a snapshot, it has to evolve and create a trajectory.

- The sentiment that migrants are bad is a sentiment not a narrative. But the sequence that ‘migrants will come and take our jobs and replace us all’ is a narrative. This then influences the behaviour of individuals or the behaviours of political organisations. These organisations aren’t only the participants of this story but also the author and sometimes the disseminators. With a story, there is always a teller and a receiver.

- Audiences always have agency and narratives sometimes take on a life of its own. A teller usually wants to tell a particular type of story but the audience interprets it according to their own beliefs and self and from patterns in their lives they draw from. They see faces in clouds.

- Social context, whereas political or cultural, influence how narratives are interpreted. Some of the tellers work in fields where narratives are explicitly used to influence society: educators (teachers, educational institutes, museums, informal educators), journalists (media, people whose tasks are to inform people), artists (creative industries; literature, art, drama), religious leaders, advertisers (PR, consultants), politicians, economists, historians.

- Theories framed as narratives. Political theories, economical theories, etc. State narrative is the job to create justifications for government policy and wars. Interpreters of reality, inextricable from providing state narratives. Each subsequently plays their own role in influencing historical, economical, and political narratives.

- An emphasis on the influence of power narratives in the social field. Given the inherent lack of consensus in the world, narratives ask how consensus is established and how are counteractives handled and challenged? Narrative isn’t just a method of study for academics, but a method of interpretation and understanding. There’s a difference between analysing how narratives work and interpreting through narrative.

Some exercises followed the initial discussion on narrative which were fun to carry out as a group, and led to some very interesting examples being provided. For example:

Have a discussion on ways that economic narratives function in our lives. How are we familiar with narrative functions within an economic setting?

- Bitcoin and NFTs (value controlled by narratives of scarcity and limited availability).

- Value of unrestricted resources (diamond) vs limited resources (cherries).

- Philanthropy and individual narratives created as a result (then shape sociological values).

- Free-range eggs (how social constructs [freedom] = greater value).

- Daily lives (saving, working to live, value as a worker/cog in the machine).

- Economical historical events as shaping sociological and historical narratives.

- Pitching art as expected to garner greater value – the sold promise of ‘investment’.

- The individual vs the collective (narratives of consumerism and wealth and consumption – how it’s portrayed on social media).

- The Gamestop phenomenon and how social media influenced the narrative there.

- The purchase of Twitter (X) by Elon Musk and the false narratives it generated and continues to generate today (the fact checking element of ‘X’ to help ‘control’ the narrative).

&

How are stories created and manipulated to understand economic narratives in our lives?

- The De Beers’ campaign for diamonds which drove up the market value and rewrote historical narratives in certain parts of the world (Botswana, Congo, South Africa).

- The toilet paper shortage during the coronavirus pandemic (2020-2021) which drove up the value of toilet paper and restructured ideas of proprietary and essential means. Thus influencing a sociological narrative. Fearmongering and stockpiling created a demand that couldn’t have necessarily been foreseen. Social media resulted in a domino effect that resulted in a global shortage. It became part of the pandemic’s eventual historical narrative.

- The 2021 Suez Canal crisis that affected global trade but became a global meme (the Ever-given meme). We become passive participants through social media (or active if we choose to share), and receive information on economic crises differently. Stories are subsequently created from the many co-authors that participate online. By buying into it (whether NFTs, bitcoin, toilet paper fearmongering, or participating in memes) participants ‘jump on the bandwagon’ in an effort not only to participate, but to play a role in the shared future that is being created. There is an importance we attribute to being ‘part of the (eventual) narrative.’

We concluded the first day with a fascinating lecture by the brilliant Prof. Frederica G. Pedriali who touched upon some interesting points such as:

- Narratives as structuring (an environment), reducing (complexity), moving us (creation motion and emotion). Looking deeply into the human past and the deep future as well, broadening the chronological perspective we cast upon this topic.

- Whatever it is to be a mobiliser in the world has to mobilise as a story. To mobilise towards war or towards peace requires narrative, requires appending a vision for a mobilisation. Reset is a point of friction nowadays within ongoing mobilisations. We demand change, we want a better future, we want a better world.

- There must be a stronger bond than the same blood or same genetic pool. This is the point of friction when it comes to resources and greater numbers of people. What is interesting in the disposal of worlds is the rapidity in which they can collapse.

The second intensive day focussed on the initial field trip at Dynamic Earth and then expanded into a discussion on the group project and intended areas of study.

Some key points from the class discussion of the field trip were as follows:

- Dynamic Earth works in collaboration with Third Generation in part to create narratives through educational workshops and a curriculum that conveys research in an accessible manner. The careful effort to convey information through chronology and a diachronic approach that is delivered as a story and allows us to learn through the passing of time. The importance of survival and durability in the world of nature, such as through starfish and grass. It also placed the importance of humans to the side, momentarily allowing us to think of the place we inhabit as part of a wider picture. There is a sense of responsibility that develops as a result of this realisation. A sense of scale and embodiment.

- The workshop pushed economics as a central part of the climate crisis and placed importance on a monetary angle. This created a debate within our group on the workshop’s effectiveness and limitations. The importance of empowering children as a result of the workshop.

- It pretends to talk about climate justice, but the spokespeople came across as token figures that distanced the kids from understanding how they can become warriors of change. Climate change and social change are at the forefront of this narrative and need to be conveyed through time constraints, which the workshop very much has.

- However, there needs to be an existing economical structure that exists in order for the young visitors to understand how the financial world operates and its rule in a climate change narrative. This could be introduced firstly in the classroom and then continued in the workshop. It is vital to understand how money works, and how it turns the world in order to appreciate its importance in a larger, environmental narrative. We must use the local to contextualise the global within the walls of the classroom.

- Visual interactions and tactile prompts, video and kinaesthetic experience through use of senses. Makes for a more memorable and sensory experience – you connect to the different elements at play and personalises it for those experiencing it. The smell of the rainforest or of the volcano immersed the visitor in the setting, blurring the boundaries between individual and narrative. The sensory memory triggers an emotional response – it was fun and playful. From a very young age, we learn from play – learning becomes a participative and group experience. The use of light and darkness to guide us in experiencing different realities. The absorption of narration through the five senses – we become co-authors in forming our final interpretation of a narrative. Always consider the intention behind any narration, any change made to it, and any mistakes, contradictions, or limitations in the narrative.

- The people who put the exhibit together are the original narrators however, and influence our takeaways from the experience. Changes made – why? Lack of funding meant some exhibits hadn’t been updated since its opening in 1999. The most recent update was the Deep Sea exhibit which had been funded by Atlas in 2021. The out-of-date portions in the narrative as a result of funding, resulting in a narrative that’s limited by funding and incomplete.

- The representation of indigenous people in the exhibit. Some of the exhibits portrayed indigenous people as collaborators in the worsening of climate change, rather than giving them a voice to explain how different life is and how it has changed as a result of other, global effects. The original ‘narrators’ were old white men who took away voices from other perspectives which might have enriched the overall narrative. There were literal cardboard cut-outs of indigenous peoples which encapsulated their voices and role as a whole.

- Finding out how people ‘out in the wild’ interpret narrative is essential to a collective and cohesive narrative. Collecting feedback in response to certain exhibits – how will you react in response to these exhibits? The wide range from re-using a water bottle to becoming a marine biologist. The workshop and exhibits don’t exist in a vacuum, they exist as part of a larger curriculum – the Scottish Curriculum for Excellent. An institutional framework, with parameters set on the topic and objectives of the workshops delivered. Objectives as a checklist.

- Dynamic Earth represents Earth’s history “from beginning to mend” (on an entry plaque). The contradictory element of first presenting us as human specks in the ‘time machine’ and then, through a sequential tour, delivers the eventual message that it’s up to us to ‘mend’ things.

Our group are currently working on putting the group presentation together, with our area of focus being politics and the sub-topic being explored: The Girlification of Politics: Tik Tok trends and their role in the Russia v Ukraine war.