I first encountered Erin Shirreff’s work at the Common Guild gallery in 2017. The exhibition, a group show alongside Vanessa Billy and Edith Dekyndt, entitled ‘Slow Objects’ was taking place through a typically stark and enchanting Glasgow winter.

Entering into the hall of the gallery, I was uncertain what to expect. In a room to my left, dimly lit, my eyes were drawn to a CRT television set. The television was displaying Erin Shirreff’s piece ‘Sculpture Park (Tony Smith)‘ (2006). I was immediately fixated. The atmosphere of the space had a gripping and austere presence, the room bathed in a kubrik-like uncanny, as the fuzzy and mysterious images of Shirreff’s film beamed forth from the screen. Between the flickers of snow and shifts in exposure contained within the film, other elements of the room were made visible – the gallery’s majestic fireplace, at the foot of which rested a piece by Vanessa Billy entitled ‘Refresh, Refresh (Mould Squeeze)’ from 2016. The title of this sculpture could not have been more apt for the space. I felt myself regenerating/repeating/shifting, doubting and reconstituting that which was around me. The doubt of that which is put in front of me was familiar given the socio-political atmosphere of our time, it being so eerily pleasurable was not. If I could revisit one exhibition exactly as it was at a point in time – I would go back to this room.

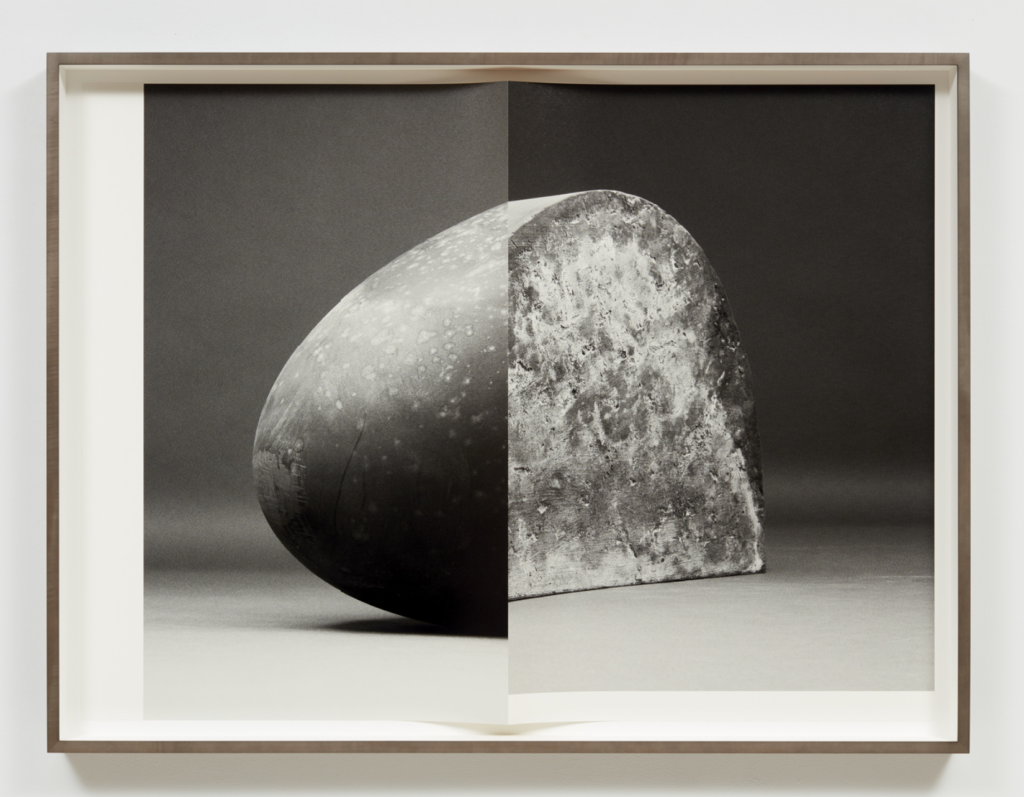

Opposite Billy’s piece, hung on the wall just by the doorframe was a second Shirreff work, a framed pigment print entitled ‘Relief no. 3’ (2015). This was my first encounter of a trademark aspect of Shirreff’s practice; the printing of a photographed sculpture, that is framed in such a way that preserves a bend or a fold in the paper – accentuating the complex relationship between two and three dimensions that is often taken for granted in photographic reproductions of sculpture.

Installation View of ‘Slow Objects’ at the Common Guild, 2017.

Photograph by Ruth Clark.

For me, what makes Shirreff’s work not only so appealing but so necessary in conversation about contemporary sculpture is how it so deftly moves between two, three and four dimensions. It can often feel it is subverting one by drawing attention to another. In my view, to work today as a sculptor is to have to consider, with as much if not more significance, how you present your work in two dimensional reproduction, as well as how it is encountered ‘first hand’ so to speak in three dimensional presence. The word reproduction is itself problematic here in the sense that so much of contemporary sculptural process can be informed and manipulated by the will of photographic representation. Therefore, what is it to say a work is reproduced in image if image was so much a central part of it’s initial production in the first instance?

I find myself increasingly drawn to exploring this in my practice but like with many questions on aesthetics facing our generation of artists, it can be challenging not to feel like one must dedicate their entire practice to the analysis of how we make work today, rather than just going on and making the work. This, again, is why I find Shirreff’s practice so relevant. Her work manages to navigate so many pertinent questions on the nature of the contemporary artwork while simultaneously occurring as one.

Take, for example, the aforementioned piece ‘Sculpture Park (Tony Smith)’ (2006). Without any prior knowledge, like myself upon encountering the work in the gallery for the first time, a viewer could well assume that this is a considerably lo-fi video recording of snow falling upon some of Tony Smith’s renowned, architectural forms of public sculpture. An image of intense romanticism, mystique and intrigue. The film conjures so many questions about what could have happened before or after the images were taken, indeed what was happening just out of frame during the moment of their capture. It is a magnificent albeit melancholic opportunity to allow your imagination to fully submit itself to the sublime.

However,

It is in fact a film made in Erin Shirreff’s New York studio, of a cardboard maquette based roughly on a Tony Smith work. The ‘snow’ is in-fact polystyrene. The entire piece is both an original and a copy – It’s an original copy. The discourse surrounding artifice within art is often reserved for the arena of painting, it assumed to be the medium most adept at dealing with illusion. Here, however, Shirreff shows us Sculpture’s capacity for bending reality in and out of shape and time. ‘Sculpture Park’ (2006) allows the viewer to engage in either a rigorous, existential questioning of the deceptively affective presence of an artwork or to just bathe in it’s undiscerning, Tarkovsky-esque territories – a simultaneity rarely found.

Much of Shirreff’s wider engagement with Tony Smith’s oeuvre demands us to examine the possibilities of the original in the first place and how much we value notions of authenticity seemingly possessed by artworks. Of course this is nothing new in a general sense of contemporary theory. However, where Shirreff transcends the notional and often opportunistic discourse on appropriation is a commitment to taking the work further into unknown territory. The power of ‘Sculpture Park’ (2006) is in its liminal, unknowable presence. This raises even more questions about the play of images and representation, about fabrication and reproduction – questions of real importance for understanding the position of sculpture today and for the coming years.

In her printed works, Shirreff expands on ideas surrounding the potential of the model or maquette as a finished piece, as well as exploring the use of a fold or crease in the paper to accentuate the print on the surface. Images merge and spill into one another in a way not dissimilar to the densely mediated visual language of the internet. Shirreff enacts the austere power of large-scale, modernist sculpture’s aesthetics and reproduces them in a way that makes complete sense in the digital age. The prints become moments of refinement, a suspension of the clamours of contemporary visual life, allowing you to focus on the action of one dimension shifting into another.

Erin Shirreff,

Archival Pigment Print, 40×54 in.

These moments of transition are difficult to reckon with for they often seem so fleeting. The stoic but unsettling nature of liminality is becoming an increasingly characterising aspect of life today, as we watch the 21st Century come of age through the ruins of the 20th. Abandoned shopping malls, decrepit office blocks and other architectural remnants of modern life more and more take on the mystique and fantasy of ruined abbeys or the gothic house. Through their dense black and white pigmentation and decisive framing, it feels as though Shirreff’s photographic prints offer a much needed context in which to adequately begin exploring what possibility can be found in these moments of transition, indeed how we can make them beautiful.

Erin Shirreff

Archival pigment print, 40 × 54 in

It is how her practice embraces so many forms and processes of production that makes Erin Shirreff’s work so appealing to me. I am inspired by the level of refinement and grace that can be brought to ideas I often find overwhelming in their complexity. When I look at Shirreff’s practice from the context of my own, I hope I can develop a body of work as confident and expansive over time. It is without doubt they are an artist who manages to point in the direction of the future for many different mediums without discourse dominating their work. This is a profoundly impressive feat and something I seek to imbue in my development as an artist.

Featured Image: 'Halves and Wholes' (2016), Erin Shirreff, Installation View, Kunsthalle Basel.