I cannot remember a time the world felt as raw as it does today.

It was like the infrastructure evolved into something new and irrevocably different from what it was before. The roads, the pathways, the cables carrying information – the networks we rely on for the maintenance of life became a new kind of critical. The hapless movements that I relied on to give my life meaning evaporated. The intensity of this shift is impossible to understate. I did not decide to dedicate myself to making art in order to ‘find myself’ or ‘become something’. I have a complicated relationship with authenticity, in that way. In the simplest of terms, it was a decision shaped by a need to contextualise the human condition today, in order to place myself within it, as much as it is placed within ‘me’. Then the condition of everything changed. In those early moments, I thought this might be the catalyst that would reveal the community I had been looking for, for so long. There was a naive dream that wished and hoped those who were interested in similar activities, similar ways of being, with similar levels of commitment, would appear somewhere out of the tree line. Needless to say, no such revelation. Yet.

So many factors of the last three years, not least the timeline we are currently living through, have made community feel like an alien concept. A foreign entity that taunts me as it has done for most of my life. So, my work has suffered greatly but not nearly as badly as my emotional state. I feel very hollow, these days. So much of what I used to worry about in the early days of art school has explained itself a lot more plainly now I’ve removed myself from it: we were already collapsing. Some of us just felt it more than others. It tends to be the way.

A lot of my work relates to concepts of infrastructure – not just the material aspects that characterise it but the broader understanding of what it means to create, maintain and develop infrastructural nodes or elements as an ethic. This relationship deals with facilitation and mediation as forms of space and time; there is an abstraction taking place surrounding how it is I accommodate something within the work. The processes with which I work tend to be fundamentally improvisational and such the content of anything I do feels increasingly irrelevant. This is a problem I am trying to use as some kind of opposing force in order to generate a greater understanding of what it is to make work today. I am trying to locate form.

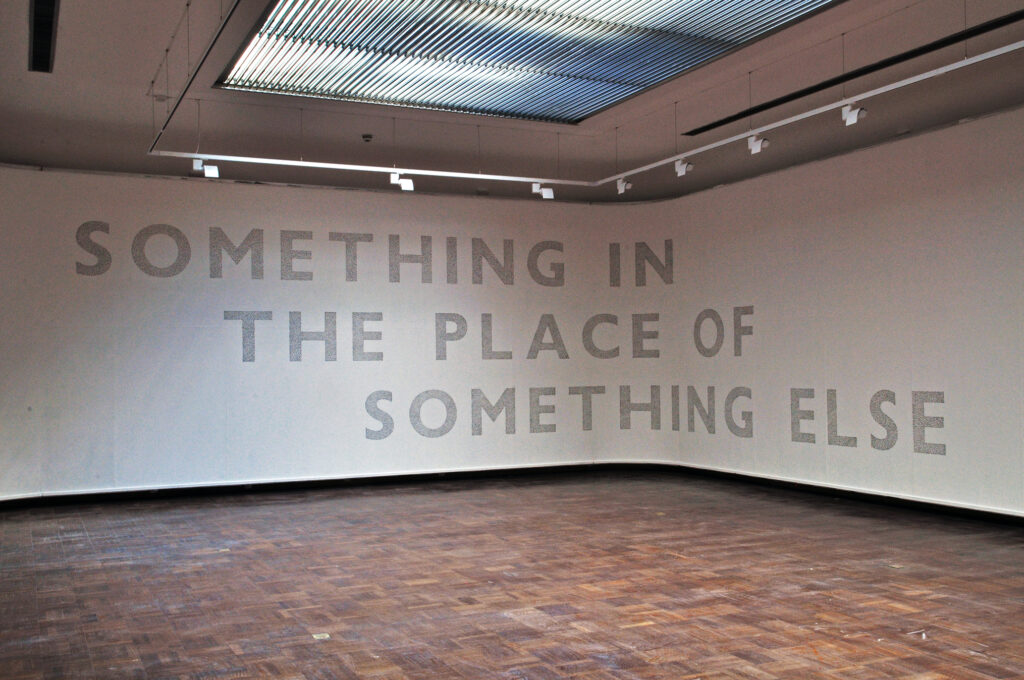

David Bellingham,

Wall Drawing,

2012.

Returning home to Glasgow because of the pandemic has been a double edged sword. I often wonder if I will ever leave this place. Part of what I found to keep me stable amidst the horrors of this everlasting year was the idea that there was unfinished business I had with the city. That I was supposed to be back here and that until I make my peace (an artwork that I wholeheartedly believe in) I would never be free. My trouble with this city is the same trouble most have with their home town. It wasn’t just the abysmal lack of care shown by management that led me to not apply to GSA years ago – evidence of those claims still seems to mount today (with ECA giving them a run for their money). It was that I felt stuck and lonely and alienated and cynical. As ever, not part of the club. As an aside, Neil Clements recent article in the inaugural issue of Nothing Personal is an exacting look at just one aspect of the problems this city’s art scene contends with today, though not felt the need to address, since it’s still been getting high on its own supply of cultural mythos.

Looking back, sometimes I wish I’d just gritted my teeth and taken a studio somewhere and never bothered with art school. Then again, I would never have met my partner, without whom I wonder if I’d still even be here at all after the last few years. It is hard to be a person, these days, never mind an ‘artist’. Words cannot express how grateful I am for their perseverance, intellect, will and generosity that has enabled me to still believe in the making of an art, whatever that may be. Indeed, so much of how I think about my research and my practice more broadly, is a salvaging of life. To take regret and perform an autopsy – softly mining for what could have been and might still be. I used to despise the extent to which nostalgia determined the aesthetics of our generation but perhaps it is necessary to see nostalgia less as a thematic mode and more a material substance that is to be deconstructed and reworked. I generally consider my work to be about communication and perception; what is profound to me is how often both those things feel like a memory. Such is the volatile ricochet between embodiment and disembodiment we live with today.

Working with context as a material is contingent on interpretations of history, themselves slippery variations in opacity. In a recent tutorial, Steven Anderson asked me if the context I am working with is a social one and to an extent I think it is. He also reflected on the importance of the instinctual (specifically removed from the reactionary). I suppose where these two notions coalesce in my thinking is how memory resurfaces and is transformed by its remembering. That looping moment that creates a new absence in place of itself. Those memories that so vividly and intensely appear without expectation are those instinctual prompts for me that are slowly drawn into a piece of work. And so, the work begins to build an eerie form of sociality for/of/with myself. Past selves, previous figures, missives and actions that converge in experience and tease narrative. In all of that, I start to choreograph something…perhaps, that resembles form.

Joan Jonas,

16mm Film Still,

1973

Fragments coming together mentally do not always translate into material or physical reality. I struggle to convey the real extent to which assemblage, appropriation and the archive exists within my practice. I struggle to get out of my head. In this way I’ve been thinking about cinema. I stress cinema over film or moving image because I am very much talking about the combination of picture, sound and spectacle in the way conventional cinema works, more than anything else. I think about the possibility of cinema as an ultimate contextual site. A container in which any combination of media seems possible. I suppose I still have time, naively or not, for this modernist idealism toward a sincere or even sublime artistic encounter created through the correct combination of variables. Perhaps it’s the failure of postmodernity that we are incapable of imagining any other mode of constructing experience – instead only able to comprehend an inheritance of it, a post-structural osmosis of the sublime. The ‘cinematic’ strikes me as a site of enhanced possibility for sculpture or artistic practice more generally; a place in which matter can occur and be metabolised inside and outside of its form, all the while relating to the whole. An organising form.

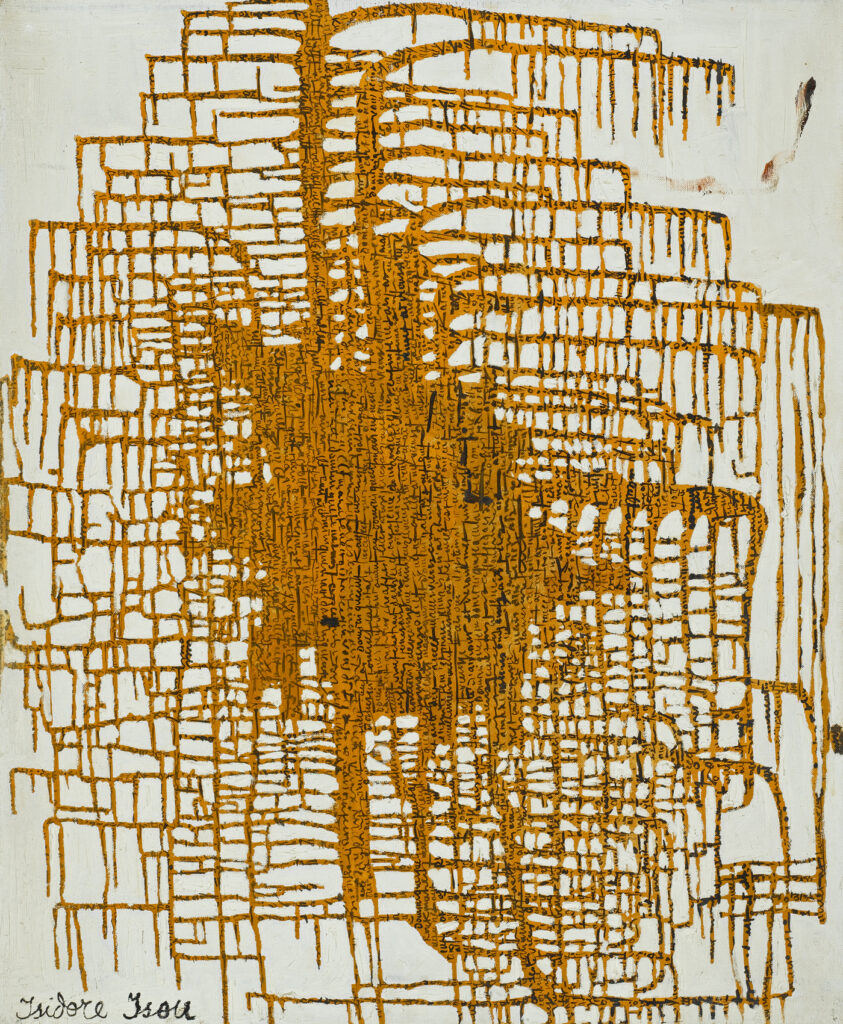

When I think about cinema and possibility, it is hard to avoid Isidore Isou’s ‘Treatise on Venom & Eternity’ from 1951. The searing, relentless belief in the capacity of cinema to produce something outside of itself is inspiring, if not with hindsight heartbreaking, to this day. Isou’s commitment to completely reinvigorating life through a reconstruction of the means of communication; through asemic writing, early forms of concrete poetry, his ‘discrepancy’ cinema (where the sound and image do not bare much relation) and his ‘hypergraphic’ paintings that freely appropriated signs and symbols, all formed an oeuvre that believed in the possibility of an artistic action that was transcendent of the political talking shop.

Isidore Isou,

Oil on Canvas,

73x60cm,

1961

In ‘Venom & Eternity’, Isou both physically and metaphorically rips the cinematic form apart, at points painting on, scratching and disfiguring the film strip’s materiality – both causing a ruckus at the 1951 Cannes and inspiring a young Stan Brakhage, who would go on to become one of the most groundbreaking and admired American filmmakers of the 20th Century. What is interesting for me today about Isou’s film is how it is evidence of what disintegration, deconstruction and re-contextualisation can mean for the impact of an artwork, in as much as it creates new worlds. Not least in the case of Brakhage who took many aspects of the methodology but transformed its uses into a radically new aesthetic paradigm in comparison.

The film is of course considered a manifesto and that is something I am wary of. Indeed, the now trademark avant-garde sneer toward the audience is something I personally cannot stand. I’m almost certain that if this film was to come out this year I would likely be kicked out of the cinema for laughing too loud. However, such is the power of the very things Isou set out to critique and ultimately attempt to overthrow – the subsumption into spectacle, no matter how off the wall – that creates for me a nostalgic pang of desire that no measure of reflexivity can hold back for long. Yet, the stasis of the present moment does lend perspective on how much experimental artwork hinges upon notions of hard-edged, fast-paced mobility or at the very least for a community to (continually) mobilise around it in order to provide context. Outside of the glowing rectangle where any artistic community is now mandated to exist, we are met with fresh absence. A new abandonment. It’s been almost a year now and I am still trying to understand how something so raw can feel so hazy. A throbbing and slow heaviness, the aftermath of an event repeating itself over and over in quasi-perpetuity, it is as horrifying as it is potent.

Stan Brakhage,

16mm Film Still,

1967

I sit each night thinking about how we salvage this. How are we to get beyond this impasse? (Or these, plural, in their multitudes). I look at what we have inherited and ask how we are to make use…what should we maintain? How do we begin to organise at scale? what can be smelted or used for fertiliser? What can become? How might it feel? When I can go out again, as we used to do; I will scrape through the rubble. And I hope a thousand narratives may bloom.

There is no love in this world anymore.

Yet, here we are. So, what next?

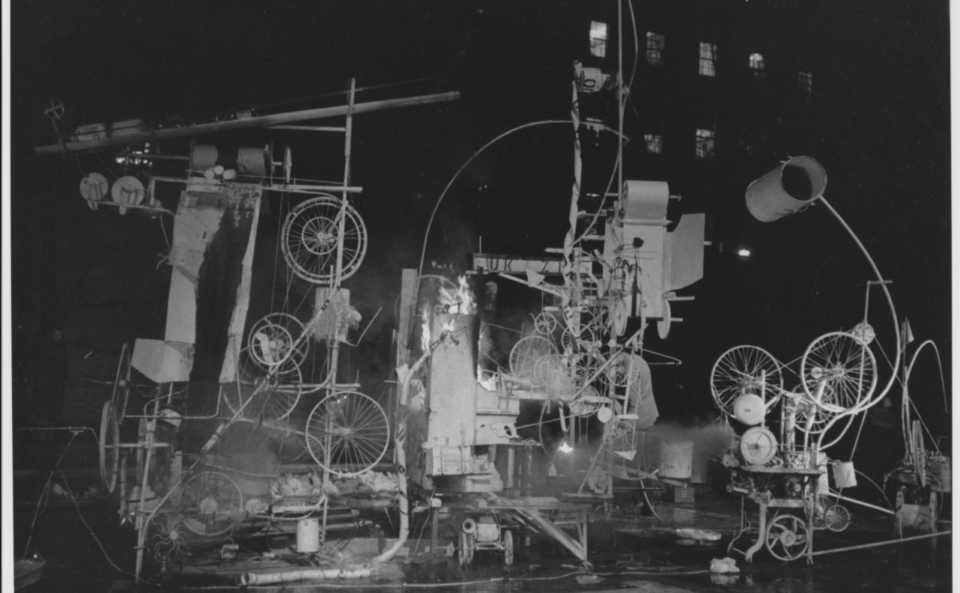

Featured Image: Homage to New York: A Self-Constructing and Self-Destroying Work of Art Conceived and Built by Jean Tinguely, 1960.