As the social model of disability provided a way to distinguish between impairments and the disablement constructed by society, critical disability studies seemed to have moved away from problematic theories of disability. However, what actually transpired was an ongoing inability to account for cognitive impairments. That was, until the concept of ‘neurodiversity’ came along.

Emerging in the late 1990s, neurodiversity has become central to the so-called second wave of critical disability studies – which aims to promote academic research into able-mindedness and cognitive impairments. Yet, as neurodiversity has also become influential within disability rights discourse, (like most good things in academia) the concept has obtained multiple meanings.

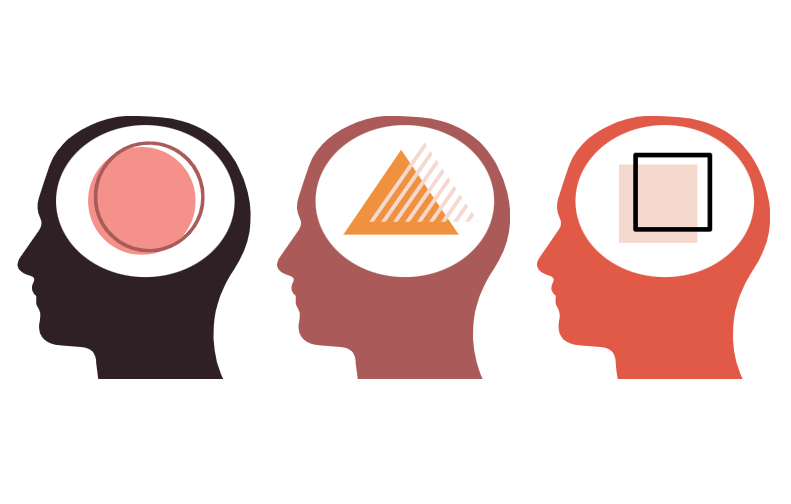

A correct understanding of each meaning of neurodiversity is increasingly important for anybody involved in disability research or activism – especially as the concept is ever-growing (at least if Google Trends is to be trusted), but often misused. This short blog post provides a quick overview to help you master the three meanings of neurodiversity:

Neurodiversity – The Noun

Not to be confused with the term ‘neurodivergent’ – which refers to brains that diverge from the norm, as through having a ‘neurodivergence’ like autism or ADHD – neurodiversity as a noun refers simply to the variation in human brains. You might have heard someone say that their ‘brain is wired differently’, and this is really all there is to this meaning – the fact that people’s brains work in different ways.

Neurodiversity – The Paradigm

Tying into disability studies theory, neurodiversity as a paradigm emphasises the variation in human brains as natural – allowing for critique of the inequalities and power imbalances that occur due to the favouring of certain types of brain function over others. Building on the social model of disability, this perspective acknowledges that disabilities can at once be both embodied by people and constructed by society, and advocates for the equal treatment of all.

Neurodiversity – The Movement

Transforming theory into action, neurodiversity as a movement advocates for the civil rights and equality of neurodivergent people. Emerging from the autism rights movement in the 1990s, the neurodiversity movement pushes for increased acceptance and accessibility for neurodivergent people – including through the use of global initiatives like Neurodiversity Celebration Week.

As has been hinted at within this blog post through the mention of neurodivergence and neurotypes, there is an abundance of additional terminology associated with neurodiversity beyond these three core meanings. However, as this post only intends to act as an introduction to the concept, I encourage readers to explore neurodiversity further – as through reading Dr Nick Walker’s blog, Neuroqueer, for a thorough (but accessible) overview of key terms, or the publications of Elizabeth Pellicano for insight into academic work on the topic.

Similarly, if you are interested in the neurodiversity movement’s mission to challenge discrimination against neurodivergent individuals, please consider sharing this blog post in honour of Neurodiversity Celebration Week, and looking further into the initiative. Greater understanding of neurodiversity can only aid the acceptance of all types of diversity, so I encourage you to get involved.

Key terms:

- Able-mindedness – the socially and culturally constructed norm of a non-disabled mind.

- Cognitive impairments – injuries or conditions that impact cognitive function.

- Neurodivergent – people whose cognitive function differs from the socially constructed norm of able-mindedness.

- Neurodivergence – cognitive impairments that make a person neurodivergent.

- Social model – a framework that argues that ‘disability’ is not innate, but is constructed by the societal barriers faced by people with impairments.

References:

Botha, Monique., Chapman, Robert., Giwa Onaiwu, Morénike., Kapp., Steven K., Stannard Ashley, Abs., and Nick Walker. 2024. “The neurodiversity concept was developed collectively: An overdue correction on the origins of neurodiversity theory.” Autism 28(6), 1591-1594. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613241237871.

Owens, Janine. 2015. “Exploring the critiques of the social model of disability: the transformative possibility of Arendt’s notion of power.” Sociology of Health & Illness 37: 385-403. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12199.

Ne’emanElizabeth Pellicano. 2022. “Neurodiversity as Politics.” Human Development 66 (2): 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1159/000524277

Pellicano, Elizabeth., and Jacquiline den Houting. 2022. “Annual Research Review: Shifting from ‘normal science’ to neurodiversity in autism science.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 63 (4): 381-396. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13534.

Walker, Nick. 2014. “Neurodiversity: Some Basic Terms & Definitions”. Neuroqueer. https://neuroqueer.com/neurodiversity-terms-and-definitions/.