In early science communication it was often assumed that the chief goal of the communicator is to “fill in the knowledge gaps” for their intended audience. By filling in these gaps, the audience acquires sufficient tools to understand science generally and make good decisions about issues like climate change, or, important to us here, healthcare. This is what Mol calls a ‘logic of choice’ strategy (2008). For museums with a focus on the science of health and medicine, it was therefore assumed that the provision of such information was sufficient to allow visitors to leave and adopt healthier lifestyle practices, no matter that these might be. Such an implicitly educational strategy towards wellbeing has long since been recognised as inadequate and ineffective, and has freed museums to consider alternative strategies that follow a ‘logic of care’ rather than one of choice. This seeks more than to supply visitors with the knowledge necessary to make good choices, but to collaborate with visitors, to offer services, and to help support their wellbeing in amongst the complex and messy world in which they are immersed (Mol, 2008).

This shift has allowed museums to adopt a diverse array of novel strategies, all within the broader concept of “wellbeing”. Here I wish to highlight just how broad this concept truly is; touching on every aspect of a museum’s programming and outreach activities, and also adopting radically diverse approaches to the very concept of wellbeing itself.

Wellbeing initiatives in the museum are not new, but it is clear that the Covid-19 pandemic led to a rapid increase in both institutions and visitors considering museums as spaces of mental health support. In the audience agency digital audience survey, 37% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “‘I am engaging […] to reduce stress/anxiety” and 57% with “I am engaging […] to boost my mood,” and this is particularly apparent in the age range of 16-34 year olds (the audience agency, 2021). Visitors are seeing museums as places to escape from the world, and to soothe their anxieties.

There is no one singular factor, no one way in which a museum can promote this sense of wellbeing. Siobhan McConnachie from The National Galleries of Scotland lists a number of factors they recognised while developing their own programming:

We discovered it was things like bringing people together. It was giving people a focus, something new to learn. It was maybe altering their regular environment or giving them a different regular environment. It was about space to reflect, and time, and it was about generosity (McConnachie, 2021).

In fact, in some cases there is evidence that even without planning, simply being a frequent visitor to a museum or gallery is sufficient to reduce anxiety as is highlighted in a 2010 study by Jennifer Binnie (2010).

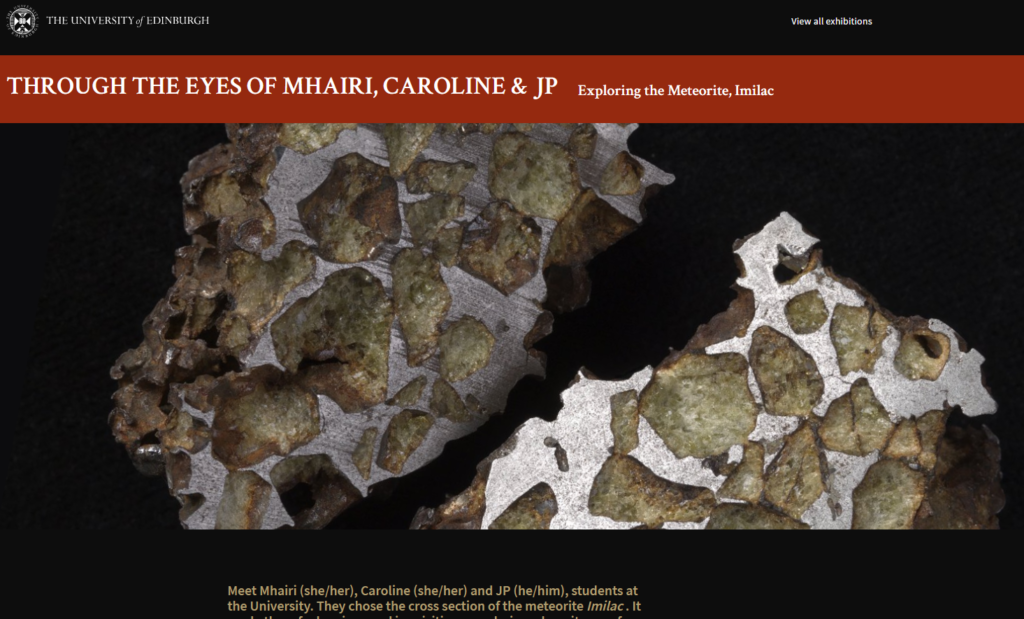

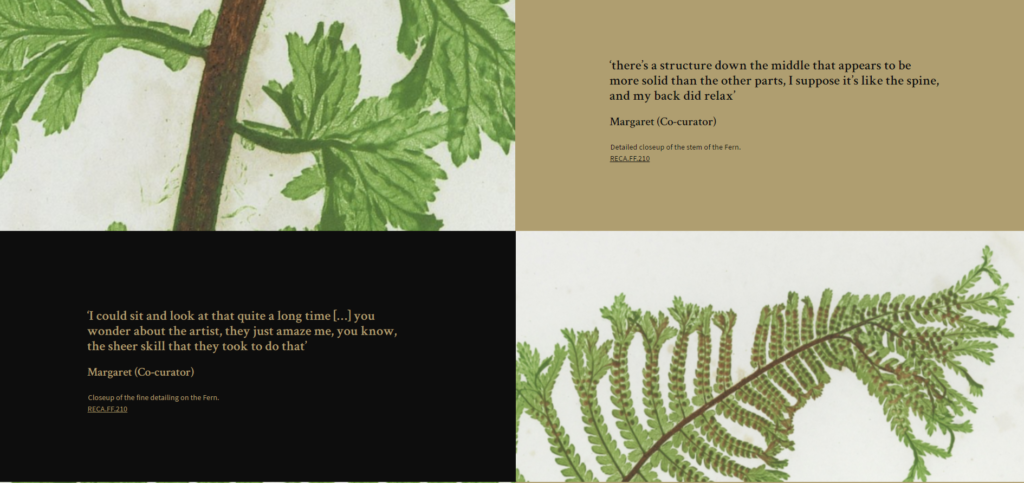

Many museums, though, have gone a step further than simply opening their doors, and they have actively sought to provision their visitors with an opportunity to engage with particular approaches, such as mindful engagement with the museum (either remotely or on site). During the pandemic, ‘mindful art’ digital pages became increasingly commonplace: with museums offering high resolution digitisations of their collections alongside mindfulness instructions (see for example the National Gallery of Ireland’s mindfulness page). On site, museums have also encouraged similar forms of engagement – with the National Museum of Scotland promoting a “wellbeing trail” and Canterbury Museums even having dedicated “Mindfulness Mondays.”

We can already see how the various dimensions of “wellbeing” might rapidly increase in number. With museums able to offer on-site and remote engagement, in the form of trails, tours, and activity workshops for children, it is clear that there is a wonderful diversity of options available.

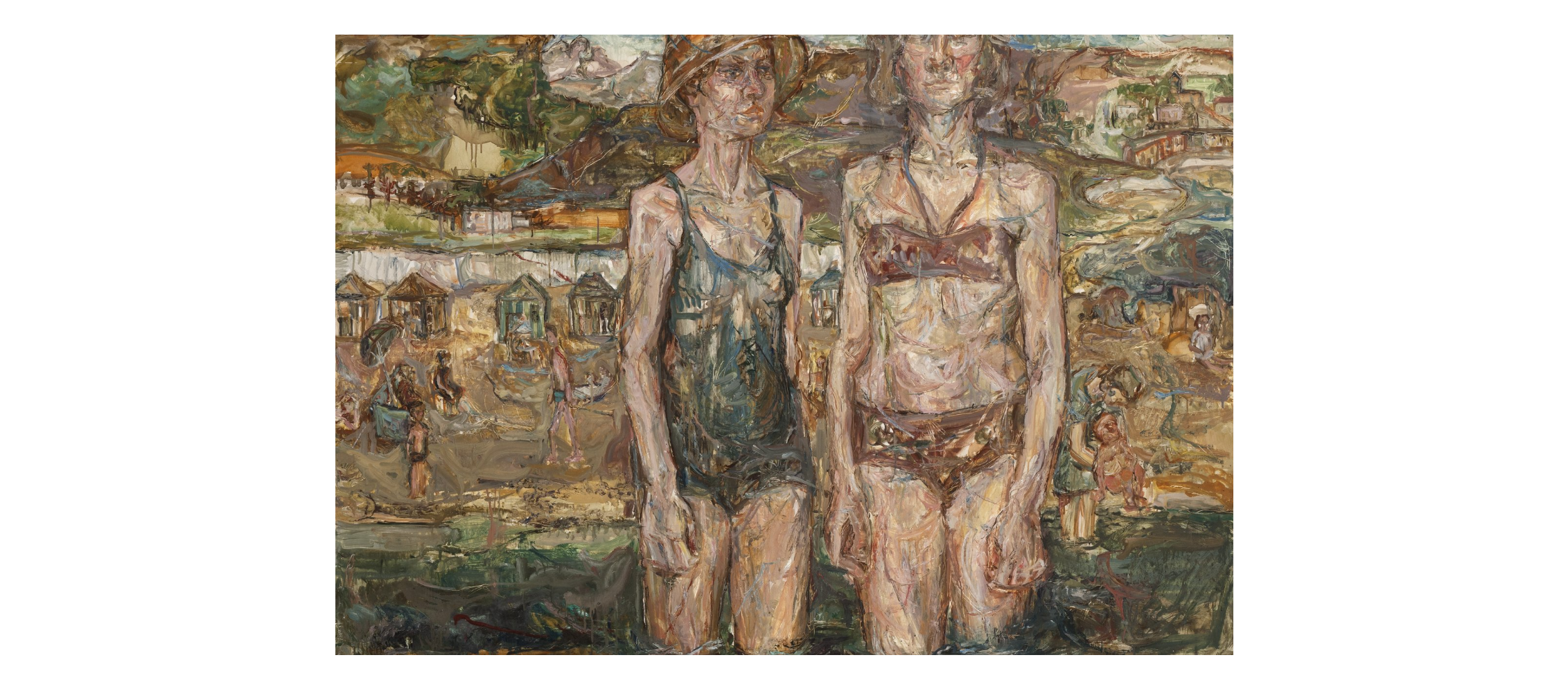

Many of the wellbeing initiatives adopted by museums cater to the visiting public as a whole, or traditional demographic subsets thereof (such as Canterbury’s focus on children). But there is a growing evidence base pointing to the value of museums and galleries as tools for supporting persons with specific mental health concerns. A recent article highlighted the efficacy of patient-museum interactions as part of “social prescription”, a form of community support for patients that supplements more traditional healthcare treatments, helping to combat social isolation, anxiety, and stress (Thomson, 2018).

Art therapy and engagement has also increasingly been utilised to support patients suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s. The Frye Museum’s “Creative Aging” series of programs offers everything from café companionship through to relaxing art tours throughout the museum, catered to the needs of adults with dementia.

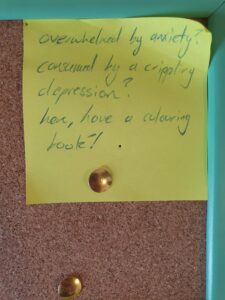

The majority of the cases emphasised so far have taken place on the institution’s own terms: within their own digital and/or physical spaces. But I would like to end by highlighting that this need not always be the case. The National Galleries of Scotland’s “Art Support Packs”, for example, were developed in collaboration with a local hospital (McConnachie, 2021). These gave patients something to work with and so relieved their boredom, and offered the opportunity to put down their thoughts. This project is not alone, with on-site object handling in hospitals and care homes also becoming more commonplace (Thomson, 2018; Chatterjee et al, 2008).

I hope I have shown, then, that we should not think of “wellbeing” as a monolithic concept. To do so would be to overlook the complexities and possibilities that come with a focus on mental health. Strategies can be approached in one of many different ways; through mindfulness, art therapy, through the provision of a social space, or through one of many other innovative and perhaps as yet unthought of pathways. A museum or gallery may seek to provision wellbeing services for visitors as a whole, or focus on more targeted groups: young children, older adults, patients in hospital, or those struggling with specific conditions such as anxiety or dementia (Clarke, 2022). It may provide these services internally, utilising its own resources, or it may look outside the institution, to support the wellbeing of patients in hospitals, children in schools, or persons in other spaces outside the traditional physical or digital institutional space.

Bibliography

Binnie, Jennifer. (2010) ‘Does Viewing Art in the Museum Reduce Anxiety and Improve Wellbeing?’ Museums & Social Issues, 5(2), pp.191-201. www.doi.org/10.1179/msi.2010.5.2.191.

Chatterjee, H. MacDonald, S., Prytherch, D., & Noble, G. (2008) Touch in museums policy and practice in object handling. Oxford, Berg.

Clarke, Ruth. (2022). ‘Age Well: supporting older people’s health and wellbeing through cultural connections’ University of Cambridge Museums & Botanic Garden. https://www.museums.cam.ac.uk/blog/2022/04/01/age-well-supporting-older-peoples-health-and-wellbeing-through-cultural-connections/. (accessed 25 April 2022)

McConnachie, Siobhan. (2021) ‘Art Helps’ Museums, Health and Wellbring Summit 31 January – 2 February 2022, online. https://www.museumnext.com/events/museums-health-wellbeing-summit/schedule/.

Mol, A. (2008) The logic of care: Health and the problem of patient choice. London: Routledge.

The audience agency. (June 2021) ‘Digital Audience Survey Findings’ The audience agency. https://www.theaudienceagency.org/evidence/digital-audience-survey-findings (accessed 25 April 2022)

Thomson, L. J. et al. (2018) ‘Effects of a museum-based social prescription intervention on quantitative measures of psychological wellbeing in older adults’, Perspectives in Public Health, 138(1), pp.28–38. www.doi.org/10.1177/1757913917737563.

Exhibitions & Programming

Frye Museum (n.d.) ‘Creative Aging Programs’ Frye Museum. https://fryemuseum.org/creative_aging/ (accessed 25 April 2022)

National Gallery of Ireland. (n.d.) ‘Mindfulness and Art’ National Gallery of Ireland. https://www.nationalgallery.ie/art-and-artists/highlights-collection/mindfulness-and-art (accessed 25 April 2022)

National Museums Scotland. (n.d.) ‘Wellbeing Audio Trail’ National Museums Scotland. https://www.nms.ac.uk/national-museum-of-scotland/things-to-see-and-do/museum-trails/wellbeing-trail/ (accessed 25 April 2022)

The Beanery House of Art & Knowledge. (n.d.) ‘Mindfulness Mondays’. Canterbury Museums. https://canterburymuseums.co.uk/participate/health-and-wellbeing/mindfulness-mondays-2/ (accessed 25 April 2022)