This is part of a series of posts exploring 360º videos, going from its roots in expositions and theme parks, to how it can be recorded using your mobile phone and used in education.

Cinéorama

The Exposition Universelle, or better known as the 1900 Paris Exposition in English, was part of France’s drive to enter the 20th century with a reignited sense of cultural and national pride after devastation of the Great War. For nearly a decade before the exhibition grounds were due to open, countries around the world were invited to bring their greatest achievements and display their cultures on an international stage, part of the event’s bigger themes of unifying people.

One of the biggest draws of the Exposition was the introduction of two of the great innovations in the world of cinema: the first wide-scale demonstration of recorded sound synced with moving image, and 360º panoramic projections. Obviously the latter of the two had the greater impact in the history of entertainment. I mean, come on, how many people actually watch films with audio?

Oh, what’s that? Most people do? Pretty much every piece of commercial film created in the last 80 years has had synchronised sound? Nobody uses 360º panoramic video projections beyond some very limited applications? Hmm.

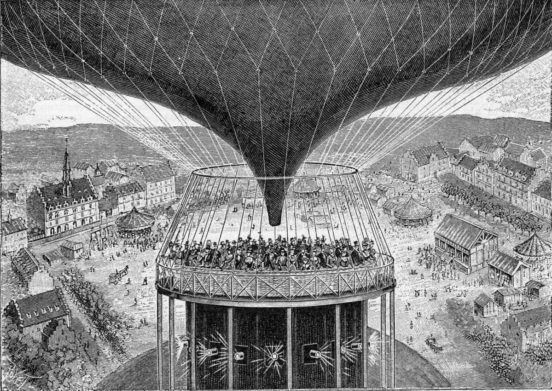

The French Cinéorama was designed and constructed specifically for the Exposition by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson, with the intention being to replicate a ride on a hot air balloon over Paris using ten synchronised projectors housed under the ‘basket’ of the stationary balloon model.

The Cinéorama lasted a glorious whole 3 days before the police shut it down due to safety concerns – one of the workmen had fainted from the immense heat of the arc lamps used in the projectors, and as these were housed directly beneath the viewing platform, it was considered an extreme fire hazard to the spectators. After the show was shut down in the middle of day 4, it has never been shown again.

Things didn’t faire much better for the Exposition Universelle – due the unexpectedly high running costs of the Exposition as a whole, it ended costing the organisers about 600 francs (around £2,000 in 2018) more per person than the cost of admission. This was the end of this streak of Parisian international fairs.

Circle-Vision 360º

The rebirth of commercial 360º panoramic films came with the opening of 1955’s ‘CIRCARAMA’ cinema in Disneyland, California, showing the short film A Tour of the West, soon followed by America The Beautiful.

The system used in Disneyland, named ‘Circle-Vision 360°’, improved on Grimoin-Sanson’s Cinéorama system in a number of ways, with the biggest difference being that instead of having the film projectors mounted under the audience’s feet (and causing a lot of fire-risks at the same time) an odd number of screens and projectors are used – this means that each projector is placed between the screens on the opposite wall of the purpose-built circular auditorium:

This clever bit of mathematics allows the bulky projector systems to be hidden behind the ring of screens, providing more a more immersive experience to the audience.

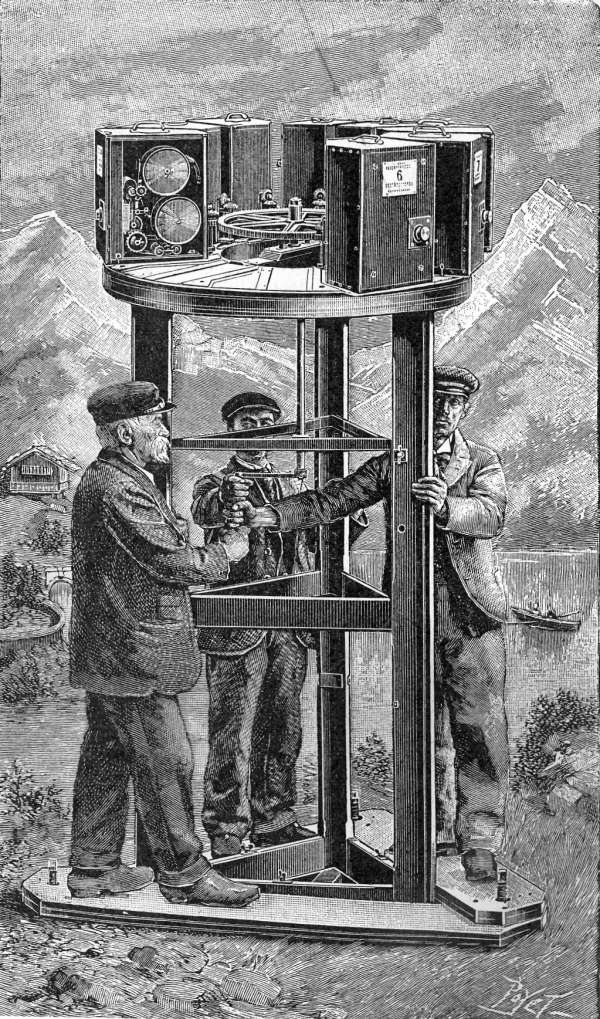

The camera system used to record the footage, however, is remarkably similar Cinéorama’s – nine cameras are arranged around a central point facing outwards, with an internal mechanism keeping the cameras in sync.

Over the years, 5 different Disney theme parks have used Circle-Vision 360º for their attractions, and while the original has now closed at Disneyland in California, and it’s international variants at Tokyo Disneyland and Disneyland Paris closing in the early 21st century, there are 2 theatres still operating at Epcot – ‘Reflections of China’ and ‘Oh Canada!’ At each of their respective country’s pavilions in the World Showcase.

Interestingly, you can actually watch this version in 360º using Google Cardboard or by clicking and dragging your mouse around the frame

Both of these act as quasi-tourism videos showing off the landscapes and cultural landmarks of each country …and the Canadian one also serves as a showcase for Martin Short’s comedic talents, so there’s that.

This idea of pure spectacle makes sense as a use for this pretty unique form of film-making, but it does highlight two of the biggest drawbacks of 360º cinema in an auditorium setting:

The first being the cost involved would make it prohibitive to film more than a few minutes worth of footage, both in terms of capturing using 9 high-quality cameras and running the multiple necessary projectors all day.

The second, and possibly most difficult to overcome: trying to craft a story where the viewer needs to constantly be turning their heads. Both of the 360º cinema formats mentioned here rely on the viewer being free to stand and turn all the way around to find and follow points of interest. Indicating where a person should be looking at all times is tricky when it might be behind them. Constantly having your characters announce themselves and give time for people to move around and look in their direction could kill the tension in your drama.

Thank you for coming along on our first journey in to 360º video. In our next article we’ll be diving in to the world of modern film and content creation for 360º and VR, and how this can be used in education.