By Glen Cousquer, David Overend, Velda McCune, Frances Ryan, Carolyn Morton, Brian Mather, Lottie Gaunt, Elaine Rainey, Françoise Wemelsfelder, Jonathan Baxter, Hannah Davies, Julia Lisa, Katie Beckman, Ellie Stirling, Catherine Finnegan and Silvia Perez-Espona

These texts were written during transdisciplinary fieldwork at Boghall Burn at the University of Edinburgh’s Easter Bush Campus. This research resulted in an academic publication (Cousquer et al. 2025), which explores encounters with a local river ecosystem as it runs through a veterinary campus and through our own being, revealing the entangled ways in which we discover ourselves to be caught up in the biodiversity crisis when we slow down and allow ourselves to become fully present and open to flow.

Badger Sett

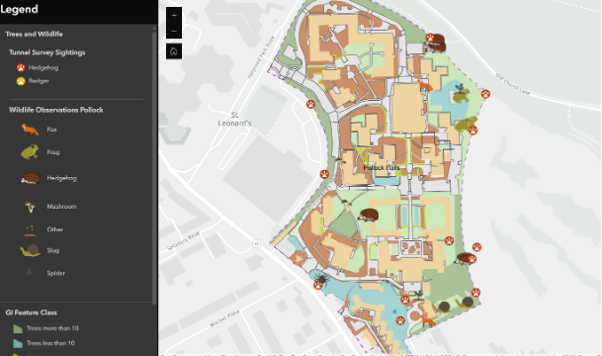

Today, the badger sett nestles in a loop in the farm track, bounded by the burn and sheltered by a canopy of deciduous trees whose roots partner the badgers in earthy probings. Here in this tiny copse they call Cowloan Wood, the badgers have dug themselves into a historic rubbish dump – an extensive heap of old rusty metal, implements, machinery, fencing materials, household mattresses and other detritus. This dumping reflects how the old agricultural college tended this site, a site that has been rehabilitated and made homely by the badgers and the trees who cling to the possibilities of life in the places we neglect. Together, they cling on and resist all manner of disturbances and intrusions. Over the years, they have seen fly tippers, badger baiters and dog walkers come and go. This is the nature of a badger, to dig in and wait it out through the winter months of hibernation and the dark months of human ignorance.

The crepuscular nature of the badger means we are unlikely to see them as they slumber underground, under our feet, during the day when we are out and about. But this does not mean we cannot learn to encounter, come to know and appreciate them for they are hospitable hosts to those who tread lightly and are willing to visit reverentially. Such willingness is essential to those seeking to learn from and become with nature. A respectful attitude and a willingness to become more relational opens us up to another way of connecting with nature through our imaginings and through paying careful attention to the silver threads of potential connections that drift through the air like strands of the finest spider silk, flickering in the light before disappearing again.

As we learn to pay careful attention to and read the field signs that testify to badger worldings – the footprints, paths, dung pits, foraging signs and the elder trees that have sprung up following seasonal feastings on berries and subsequent passing of seeds in badger dung pits – we find ourselves caught in a fine web of entanglements extending between our human forms and the wildlife who dwell in and on the land. With practise, we as visitors find these threads growing stronger and their pull and hold becoming more real. Whilst we may not dwell in the earth and be of the earth as badgers are, through their clawed digging and their foraging for and munching on earthworms, our enthralment and reverence for such places grows with each visit. Like mycelial connections between subterranean lifeforms, our own sense of entanglement spreads out and grows through the darkness and this sense of connection builds desire for stewardship and even kinship. The threads, once formed, are always with you so that whenever and wherever we encounter our fellow creatures we feel our hearts opening to them and a desire to work with them against the ever present threats of fly tipping, road developments, dog walkers and badger baiting.

Burn

Our visit to the burn saw us walking upstream, attuning to the musical flow of the waters as they murmur their wending way through snaking S-bends. We experience our entanglement with her in all our hearts and senses. Becoming with the burn, we find ourselves in a place where her soothing whispers cradle us. Waking up to the beauty and mystery of life as we breath in the rich scents of woodland and water. Finding moments of stillness and clarity letting her run across our fingers. At the same time, we feel sadness at the sight of so much human detritus and the thought that, soon, this young stream will disappear underground, travelling through culverts and along straightened sections that we have imposed. Our sadness and hauntings entwine with her calm and beauty.

Thinking with her about her journey from source to sea brings us deeply into entanglement with life giving waters and joyous vitality together with the knowledge that we as a species are betraying this gift. Our fate is entangled with hers for she runs through not just the campus but our hearts and minds. She feeds the roots of the trees shoring up her banks, in the same way that she waters our gardens and permeates out across the wider community creating an oasis of green along the edges of her blue ribbon, an oasis we could so easily widen and nurture. Nature-cultures come to life from the moment rain falls in the catchment. Is the burn ever pure? Does that matter?

Exploring biodiversity, we face something vast in its scale and relational complexity, too vast for our human mind-bodies alone. With the burn, entanglement is made manifest at human scale. The significance of a pair of dippers courting. The deep entanglement with time in the ancient trees whose roots dwell in her. The travesties of how we pollute her with dumped asbestos, litter and farming chemicals. The stories and communities that connect there. Through this and more she helps us stay with the messy dualities of local and non-local. When will we wake up to magical flow of life and resacralise it? When will we realise the burn is good to think with? Who matters to the river, who does the river matter for? Matterings matter as we hospice modernity [1].

Wishing we could live our lives like a river, constantly surprised by our own unfolding, we are reminded of the flow of the universe and of the need to return to source, to resource ourselves in the present moment where we can best water the seeds of our shared future. Where does this lead us, how can we and our students think collectively with her to find steps forward into healing ways of being with the world? How does becoming with a burn help us nurture flourishing? Nurturing students … nurturing entangled biodiversity. How do we become with a burn and how does that change us?

Barriers

The fence, the hedge, the gate, the rubbish tip, the depth and speed of a waterway, the rotting wooden bridge. These ‘borders, bulwarks and barriers’ slow us down and direct our movement through the site (Akómoláfe 2018) . At first glance, they might not lend themselves to entanglements. But what if they can be understood as Bayo Akómoláfe perceives them, as ‘active agents in our becoming, tangible producers of the real’? This would require us to look again and to recognise that slowing down and moving differently are sometimes precisely what is required. Looking through the barrier, looking from within the barrier, thinking about how the barrier connects us with what is beyond it? What are those connections, where are those connections rooted, what do those connections connect us to?

We pass a hedgerow and peer into its tangled branches to see the plastic guards and chicken wire that were used to guide and protect the former hedge saplings. This hedge is not so hedgehog friendly, but Elaine suggests that badgers could probably pass over the metal barriers without much bother. We follow the path through the mixed woodland and note how the new birch trees are still bound in plastic, years after they were planted. Other saplings are surviving the roe deer’s passage without the need for such protection. The inaccessibility of the muddy, steep winding path, which crosses the burn over rickety bridges, means that we need to be mobile as we negotiate the shifting terrain. Not everybody would be able to come with us. The whole site is a lesson in inclusions and exclusions: we need to protect this place and prevent the new housing development from bringing too many people into a fragile ecology. But welcoming in, rather than keeping out, sits better with our aspirations and ethos.

As the geographer Doreen Massey has suggested, “multiplicity, antagonisms and contrasting temporalities are the stuff of all places” (2005, p.159). There are therefore no hard and fast rules, and universal politics are not possible. Opening or closing space is not necessarily good and bad respectively. There are features which may be perceived as a barrier (such as hedgerows) but are in fact a vital resource for wildlife who use these features as regular pathways, for cover or for good foraging opportunities. Boghall Burn is bordered, hemmed in, and marked by multiple barriers. Some of these need to be removed, torn down, challenged. But we also need to leave many in place, to maintain them, to create them.

Figure: Amidst the roots of a beech tree whose roots drop down towards the burn, a vixen and her mate have raised a litter of cubs. The vixen above encourages one of her cubs to venture out and explore whilst the dog fox provides reassuring presence as the cub returns to the shelter of the earth.

Notes: [1] This turn of phrase draws on Donna Haraway for whom it “matters what matters we use think other matters with, it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with, it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.” (Haraway, 2016, p.12).

References

Akomolafe, B. (2018). These Wilds Beyond our Fences: Speech by Bayo Akomolafe at the Unitarian Universalist Congregation, Santa Rosa • Writings – Bayo Akomolafe. Bayoakomolafe.net. https://www.bayoakomolafe.net/post/these-wilds-beyond-our-fences

Cousquer, G., Overend, D., McCune, V., Ryan, F., Morton, C., Mather, B., Gaunt, L., Rainey, E., Wemelsfelder, F., Baxter, J. and Davies, H., 2025. By Leaves We Live: Entanglements with the 30× 30 Biodiversity Challenge on Veterinary Campuses. CABI: One Health Cases, p.ohcs20250019.

Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press: Durham, NC.

Massey, D. (2005). For Space. Sage: London.