Hedgehogs are nocturnal so there was little possibility of seeing one when

my new colleague, Elizabeth Vander Meer, led a small group from the University of Edinburgh’s Sustainability in Education Research Group to the student accommodation at Pollock Halls, where there is a healthy population. In fact, a sighting would have been concerning, perhaps indicating injury or dehydration, so none of us would have liked to encounter one that day. An unusual adventure then: to move close but never reach each other; to search but never find. This is how hedgehogs co-exist with us in the urban environment. Their time is when most of us are sleeping; their place is in the gaps and disregarded spaces of our busy city lives. Every now and then, paths cross and these prickly night wanderers reveal something of their hidden worlds.

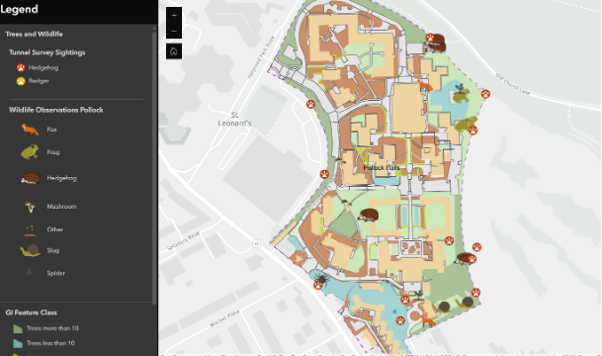

As part of the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative, Elizabeth and her colleagues have been mapping, recording and documenting the journeys and behaviours of the University’s hedgehog community (Cousquer et al. 2024). Their work has led to rewilded corners of the campus, new shelters made of logs and targeted planting, training programmes, surveys, community engagement, signage, and student research projects. In 2022, the University was awarded Gold status for ‘embedding and sustainability of continued actions as well as wider engagement with local and regionally based communities’ (p. 111). And why all this hard work? Well, habitats are reducing, fatalities due to traffic are on the rise, water can be hard to find, the climate is becoming less predictable, and populations are significantly declining. Hedgehogs are now classed as vulnerable to extinction in the United Kingdom. If we can prevent this from happening, then maybe there is hope for us too?

We walked together from Moray House, where many of us work in Education and Sport. The route took us along the edge of Holyrood Park with Salisbury Crags above us and a deep blue sky above them. As we stopped for a moment at the bottom of a grassy bank off the main path, a man with an expensive looking camera asked us if we were the butterfly group. On learning that we were in fact in pursuit of hedgehogs, he made his apologies and was quickly on his way. Funny how humans do that, I remarked: separating the natural world into specific species and areas of interest, when of course everything is entangled. Elizabeth asked us if we had seen any hedgehogs recently and the group’s responses were bleak. Some – myself included – had not seen a living, healthy hog since our childhood. Most had seen dead animals on the road in recent months. Only one or two had regular visitors to their gardens in the evenings. We walked on, keen to reach the hedgehog-rich environs of the student halls.

As we arrived on site, Elizabeth shared the evidence of prickly presences. This included the most wonderful image I have seen in some time. Using a tunnel rigged with ink and paper, the team had captured a moment of passage – tiny hedgehog footprints left on a crisp white canvas. The reaction of the group to this image was like a gaggle of grandmothers meeting a newborn. Hedgehogs seem to move even the most cynical academic into gushing adoration and this group was far from cynical. We also saw footage from a camera trap. A brief glimpse of a hedgehog as it approached the tunnel, then a badger trying unsuccessfully to squeeze its bulky frame into the small opening, then a fox taking a more aggressive approach. All these residents of Pollock Halls, living here without the exorbitant fees paid by their student co-habitants.

In the lead up to the walk, Elizabeth had shared an article with us. Exploring the idea of Storied-Places, Thom van Dooren and Deborah Bird Rose (2012) consider a colony of penguins and a flying fox camp in Sydney, Australia. They explore the ways in which ‘these animals understand and render meaningful the places they inhabit’ (p. 1), pointing out that ‘much of what they respond to in the city was not meant for them’ (p. 19). The authors propose an ‘ethics of conviviality’, which would put the burden back on humans, prompting us ‘to find multiple, life enhancing ways of sharing and co-producing meaningful and enduring multispecies cities’ (p. 19). Walking with this idea of a city storied by hedgehogs led us to think differently about the places that we passed through and stopped within. We were becoming attuned to borders and barriers, noting places of safety and vulnerability and imagining ourselves into the lifeworld of the hedgehogs. This enabled a different quality of observation and conversation, and opened up the possibility of creative, experiential modes of enquiry.

For the next part of the session, we gathered in a hidden area of woodland bordering Prestonfield golf course for a workshop activity. I invited the group to work in pairs. One person was tasked with exploring the features of the site that Elizabeth had pointed out and the other would document this investigation with photographs, notes, drawings or diagrams. At this level, the invitation was simple and straightforward, but I also hoped that the group would be up for a slightly more leftfield approach, so I also gave them the option of doing this task slightly differently. The explorer would look around this place as a hedgehog, or at least with hedgehog-like ways of sensing and moving through the site.

The point was not to pretend to be a hedgehog (although that would not be discouraged if anyone wished to take it in that direction). Rather, the idea was to get close to a hedgehog’s way of being here – to crawl through hedges, to feel the leaf litter, to smell the ground. My suggestion was that the designated explorers should try to get a feel for the point at which they were starting to feel uncomfortable and to stay there for a while or try to move beyond it. While these participants attempted to inhabit the site as hedgehogs, the documenting partner had a slightly different role: to observe a non-human presence – passage and dwelling. This might change the nature of the task and raise questions about why we would need to do this, what would it tell us, and what does it mean for the hedgehog who is recorded in this way?

To my delight, the group embraced this task with openness and enthusiasm. Off they went into the undergrowth, testing routes, feeling their way across the site, plunging hands into leaf litter and taking seriously the possibility of being more hedgehog (or less human) for a moment. For twenty minutes, the group’s engagement with the site seemed to transform into something more playful and experimental, but also more tentative and careful. I watched one hedgehog-participant move down the edge of the site, searching for a passing place perhaps, but not finding an accessible section of the wire fence marking the border. Elizabeth had told us that the ideal habitat range for a hedgehog is 0.9 km², whereas the Pollock Halls site is around a tenth of that. This means that the neighbouring sites make a big difference, and beyond this particular fence the golf course was exposed, over managed, and beyond our reach.

As we came back together to bring the session to a close, participants shared their experiences. One of the explorers said that the task had made him feel very big, and everyone agreed that the shift of scale had been important. We reflected on patterns of movement and the need for shelter, wondered about what could be eaten. The wilder areas of the site felt safe and habitable, but the paved areas between them were dangerous and exposed. The group had enjoyed this task, and felt that it had provided a space and time to foster a more-than-human relationship with the site.

While the discussion continued, I had to leave promptly to catch a train. As I power-walked down South Bridge, dodging tourists and traffic, it struck me how quickly we can return to our frenetic lifestyles. The built-up city centre seemed inhospitable to hedgehogs, and it was easy not to spare them a thought in this part of town. Nevertheless, my afternoon’s encounter at the fringes of the built environment had offered an alternative way of being and thinking that felt hugely important. We might not often see the non-human others who share our cities, but we need to remember that they are here too. The walk and workshop had allowed us to explore an ethics of conviviality that requires a different way of designing, building, managing and inhabiting urban space. The image of the footprints is a powerful emblem for this project, a reminder that others pass where we walk.

References

Cousquer, G., Norris, E., Lurz, P., Vander Meer, E., & Gurnell, J. (2024). Hedgerows for Hedgehogs and Campus Biodiversity: A Prickly Challenge for Universities. Journal of Awareness-Based Systems Change 4(1), 101–126.

van Dooren, T., & Bird Rose, D. (2012). Storied-Places in a Multispecies City. Humanimalia 3(2), 1-27.