This text was written as we attempted to follow Karen Barad (2007) in ‘diffracting’ the contemporary city for an academic article (Cullen et al. 2024). This fragmented narrative is comprised of diverse intra-actions that occurred in the process of learning and teaching on Creating Edinburgh: The interdisciplinary city – an undergraduate course at the University of Edinburgh – including creative responses written by students during the course, photographs of spaces in Edinburgh, which are the focus of course assignments, excerpts from the researchers’ reflections during the research process. Following Barad’s example, we have provided explanatory footnotes, which give context for each fragment.

If you’re reading this, you’re likely facing the screen

Or page

Head on [1]

But if you were standing

On Princes Street in Edinburgh

At the bottom of Lothian Road

Facing East

You’d find the high street on your left

And the gardens on your right

With Edinburgh Castle looming above

There are tourists taking photos

And a group of students exploring the grounds together

You emerge from the bowels

Of Waverley,

Adjusting to the brilliant blue,

The crisp autumnal air,

The majesty of Castle Rock,

The dynamism of Edinburgh

Laid out before you

In all her splendour.

On Waverley Bridge,

Behind you,

Laughter erupts sporadically,

Punctuating the comings and goings…

To your right,

A circle of students,

Bundled up against the October chill.

A researcher among them.

Beyond, the commercial aorta:

Princes Street abuzz, tram bells, busses, totes.

To your left,

A couple poses,

One click to capture,

To immortalise the moment.

One tap to transport,

To digitise a vista.

But for you,

Immersed as you are,

This is no two-dimensional plane.

This is your reality.

Stimulating activity in the same motor-neurological regions as physically enacted movements (Barsalou & Wiemer-Hastings, 2005), reading is an embodied experience which invites not only visual representation, but a broad range of multimodal responses, including any, or a combination of, the five senses, interoceptive reactions, proprioceptive responses and kinaesthetic sensations (Rokotnitz, 2017). In reading the multimodal imagery contained in these fragments the past experiences of research participants, course tutors and researchers with(in) the city ‘flash up’, diffracting spacetimes and “de(con)struct[ing]… the continuum of history… [to bring] the energetics of the past into the present and vice versa” (Barad, 2017, p. 23). The reader is as phenomenologically immersed and materially connected — as entangled – as the participants and researchers.

You walk through the city, across Princes Street, to the New Town.

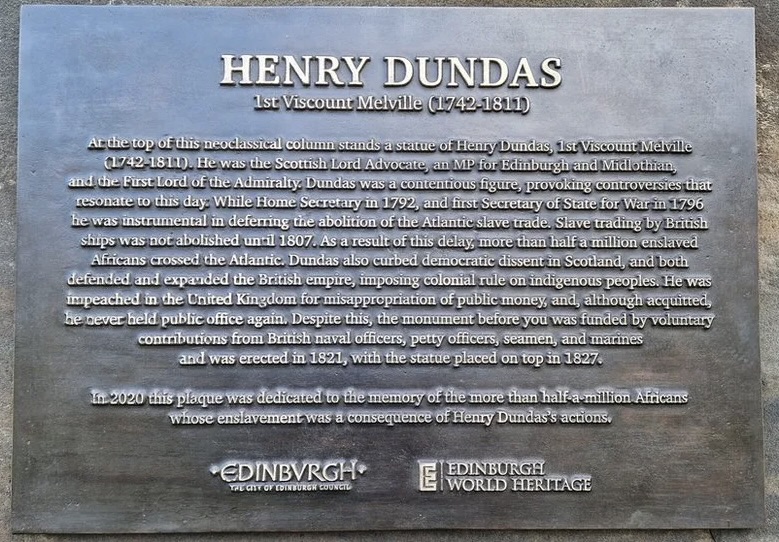

The infamous statue of Henry Dundas – 1st Viscount Melville – stands 150 feet above St Andrew Square. Between 1791 and 1805, Dundas was Home Secretary, Minister for War and Colonies and First Lord of the Admiralty. He is also argued to have significantly delayed the abolition of slavery.

To begin the Decolonising Edinburgh field week, students are invited to watch a film of Sir Geoff Palmer, interviewed for Edinburgh Futures Institute (2020). Palmer introduces this controversial figure and reflects on strategies of decolonising public monuments. Palmer is Scotland’s first Black professor. He is now Professor Emeritus in the School of Life Sciences at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh.

As a result of campaigning by Palmer and others, a new plaque has now been installed at the site. Students visit the monument together to read the new inscription and to critically reflect on the text.

Does the plaque go far enough? Do you feel that the statue should be removed? If so, should something else be put in its place?

The Researcher [2]

You arrive.

Waverly North Bridge.

Unable to discern the students

From other passers-by.

An approach:

Are you…?

Yes!

Smiles.

Introductions.

Research Ethics.

Expectations.

Invitations.

Phones out.

Recorders on.

You follow,

Neither a part

Nor apart.

Liminal.

Present.

You observe.

You reflect.

You diffract,

Becoming

Complicit

And in doing so

You are irrevocably

Entangled,

Altering the experience

Fundamentally.

What does it mean

To be here?

To inhabit,

To embody,

To be of

A city,

And for a city

To be of you?

Questions structure the discussion in the seminar room. Tutors facilitate the exchange of ideas between students, drawing out tensions and contradictions, prompting intra-action. The ‘tools’ that tutors use might be understood in Baradian terms, although they have yet to be framed explicitly in this way. Students share the documents and outputs of their field work, which are then explored by students in other groups. Questions are invited to turn experiences over and over, troubling binaries and opening up reflections into new, generative responses. This includes the creation of new field topics, which are submitted for assessment as digital portfolios comprising images, maps, tasks and questions. As Karen Spector argues, ‘If nothing new that matters is produced, then diffraction hasn’t occurred’ (2015, 449). With a topic as contested and emotive as decolonising monuments, diffraction might be utilised more explicitly as a way to read meanings through each other, without the pressure to move towards resolution. The ethics of diffractive pedagogy are informed by feminist theorists such as Donna Haraway, who argues that ‘it matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories’ (2016, 12). Creating Edinburgh emphasises the ways in which learning and teaching matters to the city and its continual creation through stories, journeys and intra-actions.

If you had been in this exact spot some years ago, a PPE (personal protective equipment) mask may have obstructed your peripheral view

Students on the inaugural version of Creating Edinburgh sat in cold seminar rooms (windows open for air circulation even in the winter). Pandemic Edinburgh has never been a popular field topic.[3]

‘I’ was teaching two seminars that year

Each week, I greeted students as they filtered in, sitting in their groups

“How was your fieldwork?”

“Where did you go?”

“What did you see?”[4]

Years later Creating Edinburgh found its way into my PhD Manuscript:

The figure of the witch has been a constant companion to my PhD process. In my final semester of teaching at the University of Edinburgh, I was working on a brand-new course called ‘Creating Edinburgh’.[5] The course design loosely mimics a ‘choose your own adventure’ novel, wherein the students opt for certain topics from a list of offerings at the beginning of the semester. The course is an interdisciplinary approach to the city of Edinburgh itself and engages with themes like, ‘Decolonising Edinburgh’, ‘Digital Edinburgh’, ‘Literary Edinburgh’, ‘Deep Time Edinburgh’ etc. The main assessment for the course is for students to create their own theme to be added to the cache for future cohorts. One of my groups chose to pursue Witchcraft Edinburgh, and it is to them I owe much of my knowledge about witch hunts in Scotland. Thank you, Eleanor, Aimee, Sadie, and Andrew. It is because of them that I learned that the Mercat Cross located in the market centre of Medieval Edinburgh served as an execution site for accused witches. According to a plaque at The Witches Well, a memorial to those accused of witchcraft in Scotland between 1563-1736, hundreds of witches were publicly executed during this time. The plaque was placed in 1912, and states,

This fountain, erected by John Duncan, R.S.A., is near the site on which many witches were burned at the stake. The wicked head and serene head signify that some used their exceptional knowledge for evil purposes while others were misunderstood and wished their kind nothing but good. The serpent has the dual significance of evil and wisdom.

Witches then, were condemned regardless of which direction they aimed their powers; ‘the “good witch”, who made sorcery her career, was also punished, often more severely’ (Federici, 2004, 200). This lack of discrimination concerning the morality of witches is perplexing; if witches were not hunted and killed for their wickedness, what were they persecuted for?

The situatedness of this knowledge struck me, as I had been working with the text, Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation for years and had not investigated the history of witch trials in Edinburgh, the city in which I lived and studied in.

Witchcraft Edinburgh [6]

Artistic Edinburgh

Literary Edinburgh

Music Edinburgh

Deadinburgh

Eatinburgh

Haunted Edinburgh

Legendary Edinburgh

Queer Edinburgh

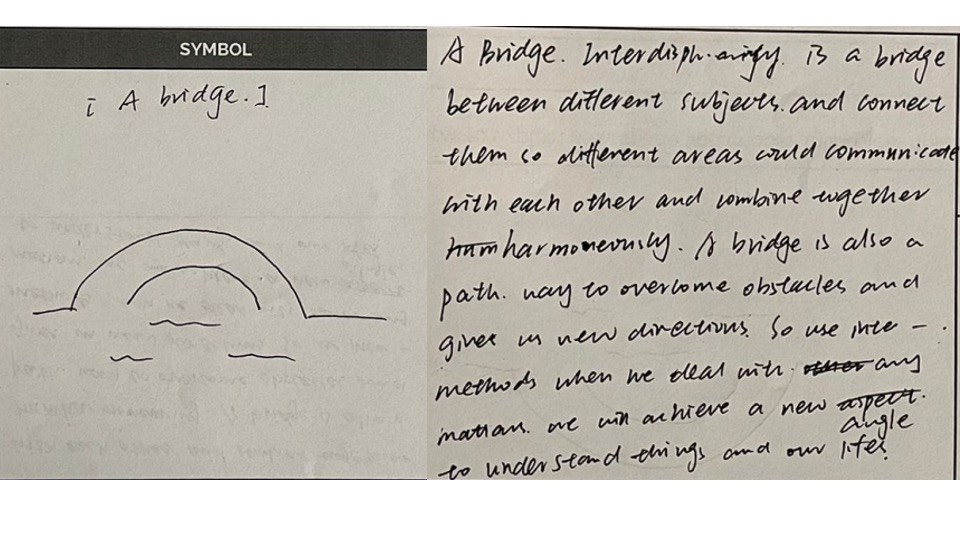

For their final assessment, students work in groups to create their own field topic. These are then made available as an open educational resource on the University’s website so that they can be accessed publicly and used by students on subsequent years of the course, as a re-turning of practice. The course avoids closing down the experience into interpretive or analytical assignments. Rather, new experiences are generated, new paths are followed, new questions are raised. The questions that students have asked through this assessment task exemplify the kind of diffractive approach that we are advocating in this article. Barad’s argument about the inseparability of entangled phenomena tells us that ‘separability is not taken for granted and this means that all phenomena—all the entanglements—are open to analysis and questioning’ (Barad & Gandorfer 2021, 51). Applying this principle to an educational experience in the city suggests that the questions that are asked (which includes the prior questions that structure the fieldwork on the course) matter to Edinburgh. This is because active questioning ensures that multiple components are kept open, malleable, subject to change. This is the meaning of the course subtitle, ‘the interdisciplinary city’.

Does the surrounding area reflect what we have learned about Edinburgh and its level of safety for the LQBTQ community?

How are educational institutions and their buildings important for a city other than just as classrooms?

How does food serve as a social tool in this community?

Why are ghost stories ingrained in Edinburgh, and how might they add to the culture of the city?

Because diffraction is an ongoing process, these questions are not only about a specific encounter with the city of Edinburgh: they also have the potential to shape ways of being, thinking, relating in other contexts.

The majority of students on the course are exchange or international visiting students [7]

After weeks of oscillating between seminar room and fieldwork, they would return to their country of study or home

What did they bring with them? What did they leave behind?

Were they changed by Edinburgh? Is Edinburgh changed by them?

Perhaps they did not return. They re-turned.

There are things about which

We educators and researchers

Have no knowledge,

No control.

What was happening

In the ‘margins’ of the students’

Lives?

Living as they were

Beyond the parameters of

This ‘Creating Edinburgh’.

Learning as they were

Beyond the boundaries of

This ‘Education’.

How to divest oneself

Of the assumed responsibility

Of the learning and knowing

Of others?

Vital contemplation.

You peer down a nearby close (those narrow, steep alleyways branching off the Royal Mile)

And you feel the wind rush through it, over you

It’s particles and physics

[1] These fragments were co-created in the spring of 2024 by authors Clare Cullen and M Winter, each drawing on their own experiences with the city of Edinburgh and the course. The latter fragments specifically refer to Cullen’s walking intraview with students on their field work.

[2] This fragment, written by Clare Cullen, captures her experience accompanying students on their field work in the autumn of 2023. The researcher’s presence-participation in students’ fieldwork with(in) the city was an integral part of our methodology. Weaving an autoethnographic fragment of the researcher’s fieldwork experiences into the tapestry of this entanglement reveals the messy liveliness of diffractive research. It does not obscure the essential administrative, ethical and logistical elements that might bookend a data collection intervention — those research protocols that exist beyond the boundaries of the data and yet fundamentally influence the experiences captured within those recordings. It acknowledges what is gained through researcher presence-participation, and what is sacrificed: a firsthand, embodied understanding of the multisensory phenomena that coalesce to create a city at the cost of influencing the students’ experiences by introducing a factor that would otherwise not have been present.

[3] Barad follows Walter Benjamin in exploring the disruptive potential of ‘a superposition of times – moments from the past – existing in the thick-now of the present moment’ (2017, 33). For Barad, this is understood through the notion of temporal diffraction, noting how an electron can co-exist at different temporal, as well as spatial, locations. While the Pandemic Edinburgh topic is not a popular choice (perhaps because this is not a temporal location that students have any desire to re-turn to), Creating Edinburgh was designed and developed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pandemic time is therefore superimposed in the present moment through a troubling of digital/physical binaries and the traces of the disrupted learning experience that characterised the inaugural year of the course. Deeper time is also superimposed on the present, as students are invited to encounter the city at a geological scale. Searching for evidence of geological processes in the city, students are asked to identify traces in the materials and shapes of the urban landscape.

[4] This section, written by M Winter, describes their experience teaching on the inaugural version of Creating Edinburgh in 2021.

[5] This is an excerpt from M Winter’s PhD thesis.

[6] A list of topics added to the cache by students over the past few years.

[7] This section was co-created by Clare Cullen and M Winter, diffracting their varied experiences as researcher and teacher.

References

Barad, K (2007) Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press, Durham.

Barad, K. (2017) What Flashes Up: Theological-Political-Scientific Fragments. In: Keller, C and Rubenstein M-J (eds) Entangled Worlds. Fordham University Press, New York pp. 21–88.

Barad K, Gandorfer D (2021) Political Desirings: Yearnings for mattering (,) differently. Theory & Event, 24(1), 14-66.

Barsalou LW, Wiemer-Hastings K (2005) “Situating Abstract Concepts.” In Grounding Cognition: The Role of Perception and Action in Memory, Language, and Thinking, edited by Diana Pecher D, Zwaan RA. 129 – 63 (New York: Cambridge University Press).

BBC (2024) Council installs new slavery plaque at Edinburgh’s Melville Monument, 18 March 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-68597359. Accessed 28 Mar 2024.

Cullen, C., Jay, D., Overend, D. et al. (2024) Creating Edinburgh: diffracting interdisciplinary learning and teaching in the contemporary city. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1151.

Edinburgh Futures Institute (2020) Shadow on the street: Edinburgh’s links with the slave trade. Film by McFall L and AWED (Goss S, McFall L, Umney D, Moats D). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrx5yQnx6QM. Accessed 28/03/24.

Federici S (2004) Caliban and the witch: Women, the body and primitive accumulation. Autonomedia, Brooklyn, NY

Haraway D (2016) Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, Durham.

Rokotnitz N (2017) “Goosebumps, Shivers, Visualization, and Embodied Resonance in the Reading Experience: The God of Small Things”, Poetics Today 38:2. DOI 10.1215/03335372-3868603.

Spector K (2015) Meeting pedagogical encounters halfway. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 58(6): 447–450.