Waterways, 7-11 May 2024, Emma’s journal

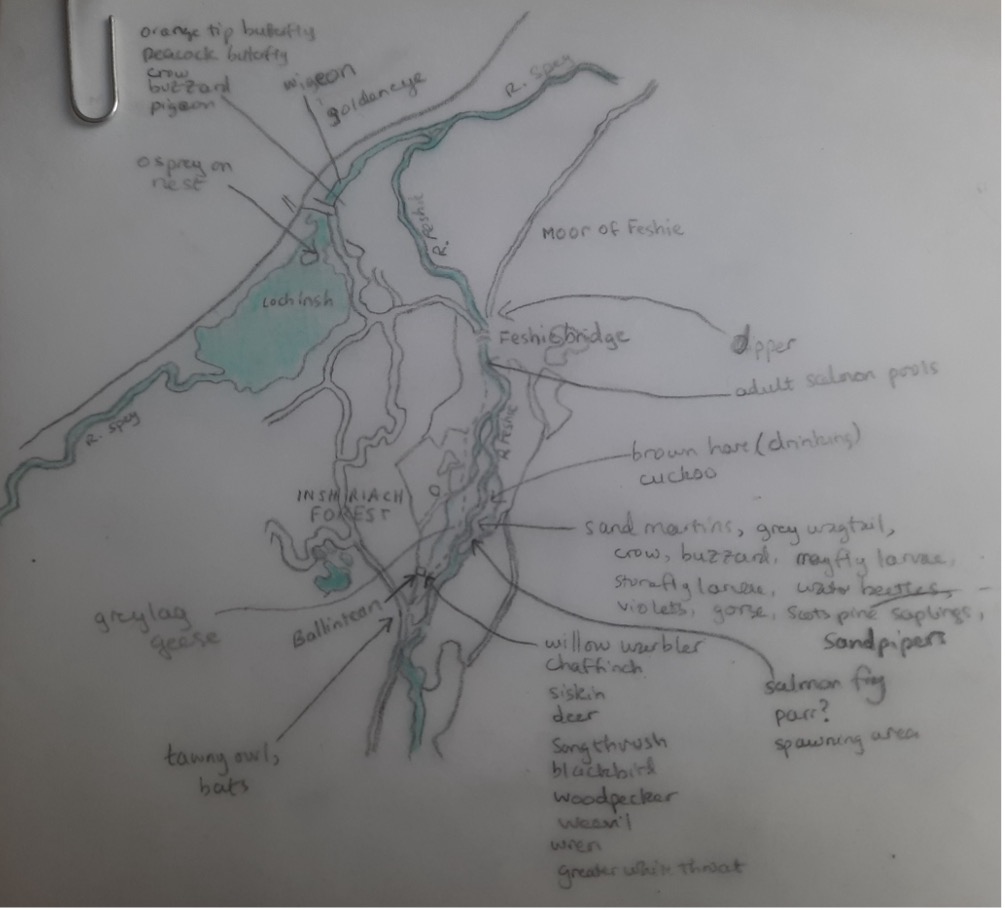

Upper catchment: River Feshie (Spey tributary) & Loch Insh

Day 1. I wake early and run with Colin down the river to Feshiebridge. After breakfast, we walk down through blackthorn and birch to the braided channels and shingle of the River Feshie. Laura leads an “orientation exercise”, something unfamiliar to me – eyes closed, moving and stretching the body, grounding the feet, awareness of sounds, smells, sensations – that leaves me feeling vulnerable and awkward. I wonder how the others feel and where this discomfort comes from. I focus on the feeling of airflow around my hand and wonder if water flow feels similar over the skin of salmon parr holding station against the river current. The fry and parr face into the current, beating their fast little lives against it. When they smolt, they cede the battle, turn and face downstream, drift and swim. This image strikes deep; it is painful to consider the possibility of turn and release from the struggle to be enough.

We discuss the early life stages of the salmon and explore the shingle, side pools and river. We scoop with a net and turn pebbles to uncover stonefly, mayfly, beetles. I find a dried-out log with a salmon’s hooked jaw. I try to just be and feel but can’t escape the urge to catalogue, to name and list the wildlife, the sensations. [sand martins, dipper, pied wagtail, crow, buzzard]

We walk on to Feshiebridge with its deep pools for adult salmon to sink into. [orange tip butterfly, newt]

After lunch we go to Loch Insch. Salmon entering this wide loch must find their way out through the narrow exit at Kincraig. A kilometre further down is where the Feshie flows into the Spey. [osprey on nest, goldeneye, mallard, sandpiper, greylag geese, crow, buzzard, pigeon, wigeon, orange tip butterfly, peacock butterfly] How do they find their way out? How do they know when and how to smolt? In a way, they reinvent anew with every generation what it means to be salmon because they don’t have a cultural map. They find their way in the way that feels right. We have expectations of our future through knowledge imparted to us by others who have already gone this way. Salmon experience expectation in a totally different way, through urges and instinct. Does this mean they are freer and more adaptable than humans? Do they have a greater capacity for reimagining? Unguided but also unconstrained and unburdened by social knowledge and expectations? What does this mean for us, now, when we have to reimagine how to be human in a world whose ecological integrity is starting to unravel?

In the evening, we share our thoughts and words from the day. This is again uncomfortable, and I wonder how much of myself I have hidden that this feels so exposing.

Day 2. Again I run to Feshiebridge, being happy to stay by the river rather than seek out a new route. The river is silver and the fringing birch trees luminous in the early morning light. I startle a hare drinking at a shallow pool. I want to run fast but the narrow, foot-worn path forces me into an awkward gait. I briefly wonder if the rewilded future will contain any smooth ways. I move off the track and realise the grassy overgrowth itself better holds my feet.

[cuckoo, willow warbler, siskin, chaffinch, crow, song thrush]

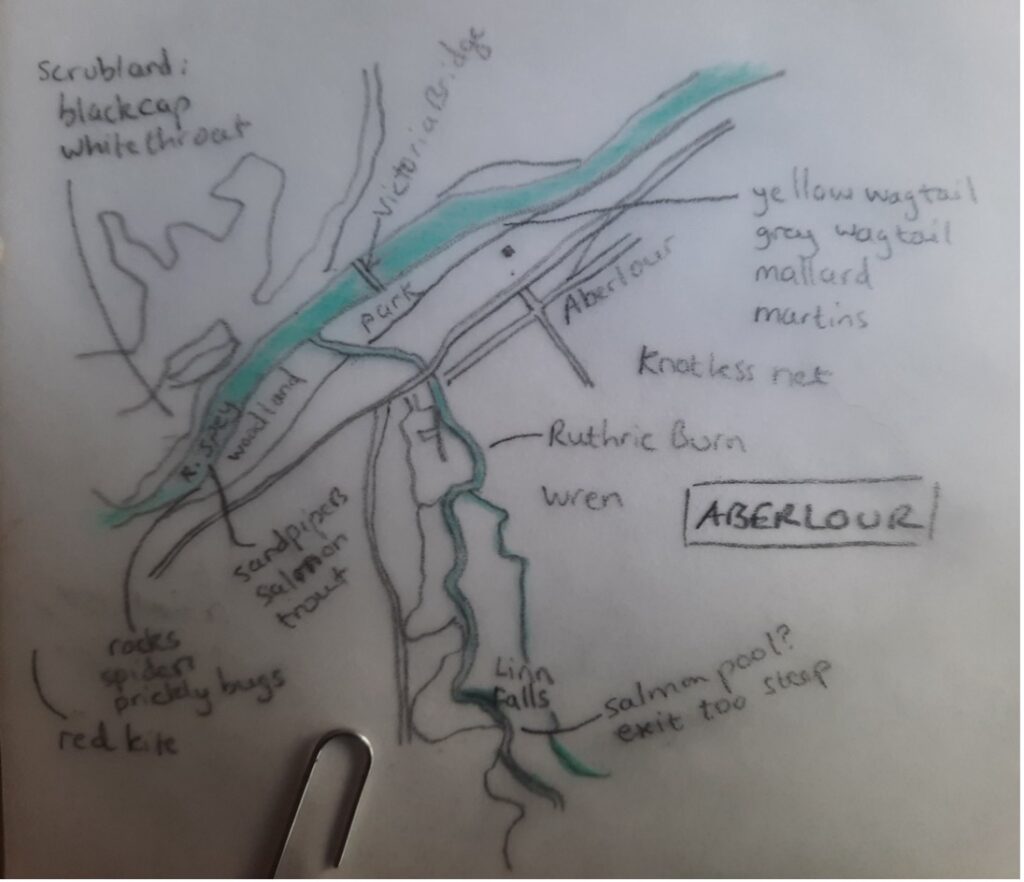

Middle course: Aberlour

Day 3. I dream vividly and wake to the dawn chorus, needing more sleep but reluctant to shut the window. I walk to the Feshie and enjoy the colours in the early morning light but don’t scramble down the bank to peer into the water or lift stones.

After breakfast we go to Aberlour where the Spey has become something very different – wide, manicured and very appealing to anglers. Down at the river, we speak about angling, catch and release, knotless nets, the ambiguous status of trout, river gardening and the constrained flow. I feel detached – from the river, from the day. We discuss climate change, warming rivers, smolt run phenology and the potential uncoupling of evolved migration cues from encountered marine conditions. [crows, jackdaw, yellow wagtail, magpie, mallards]

We walk upstream to the suspension bring and watch a rotating dance of anglers. Someone asks, why do they fish for salmon? I am struck by this ubiquitous question of the outsider, that can only be asked of anything by someone from a nonintersecting world, and wonder how the anglers themselves would respond. They aren’t detached. They have quite literal lines of communication with the river, with the salmon.

We trail through wild garlic scented woodland to a rocky perch above the river and watch the dark swirling surface. I enjoy the shedding of tiny eddies from larger ones. Fish keep surfacing with a plop but are gone by the time to turn to look and I don’t stare at any one patch of water long enough to see them. Matthew does, and sees several; he also films underwater. In scientific observation, how do we know when we’ve watched for long enough?

I feel like I can’t find a way in, to the river, to the salmon, to the day. Detached. Is this why people fish, to pluck the unknowable out of the darkness and force it to “shake hands” with us, confront, see and know us? Is this why we are uncomfortable with rewilding? The new wilderness might give nonhumans too many places to elude us. The water feels impenetrable compared with the clear shallows of yesterday’s Feshie where we could see fully to the bottom, turn stones and glimpse the inhabitants. If we can’t find a way in, a way of seeing in, do we believe there’s anything there, do we care?

I watch sandpipers. One, pipping, zips a straight line upstream. Three, pipping more so, chase each other in zigzags. They don’t seem to want a way in. (I later look up how sandpipers feed: they hunt prickly bugs by sight on the ground or in shallow water, so indeed they don’t need a way into the deeper water.)

Sitting at the edge of conversation, I hear warblers on the opposite bank. Unsure which, I ask BirdNet, a machine learning bird song recognition app. Black cap, it tells me, then wavers – Whitethroat? These birds sound very different. Has the incursion of even gentle respectful human voices into the recording made the song cryptic to BirdNet, or is the whitethroat there too and cryptic to me? I am restless to move on and find some attachment to this day.

[sandpipers, red kite, magpie, yellow wagtail, black cap]

We walk up the Burn of Aberlour to waterfalls. Salmon come this way but may not make it up the highest fall. Marie and I discuss the definition and etymology of the word “matrix” and I feel the need to understand how the mathematical definition fits in. My research involves finding a salmon post-smolt’s path through n-dimensional matrices of biophysical ocean model data. I wonder what questions an artist would ask of my data.

I want to swim but feel awkward and settle for dangling my feet in the peaty water, enjoying the different textures (turbulent, laminar, bubbly, still) on my toes. The cold water is refreshing but still doesn’t connect me to the day.

Laura and I wonder what the human equivalents are of salmon’s unlearnt knowledge (instincts, gut feelings, innate responses). Are we such a social species that we’ve lost all our useful instincts, downloaded them to the cultural cannon? (I think about cultures and yoghurt cultures and how cultured things are easier to digest).

I think about how our salmon population “box” models map onto this multifaceted riverine landscape. They seem such an inadequate representation. Our smooth-sided boxes leave nowhere for the salmon to hide. Lack of complexity hinders accurate representation of processes, e.g. coexistence theory. We need to recognise the right level of complexity – the number of niches or modes of being that the landscape wants to split into, the number of boxes needed to catch the salmon. Rewilding is about allowing mess and complexity.

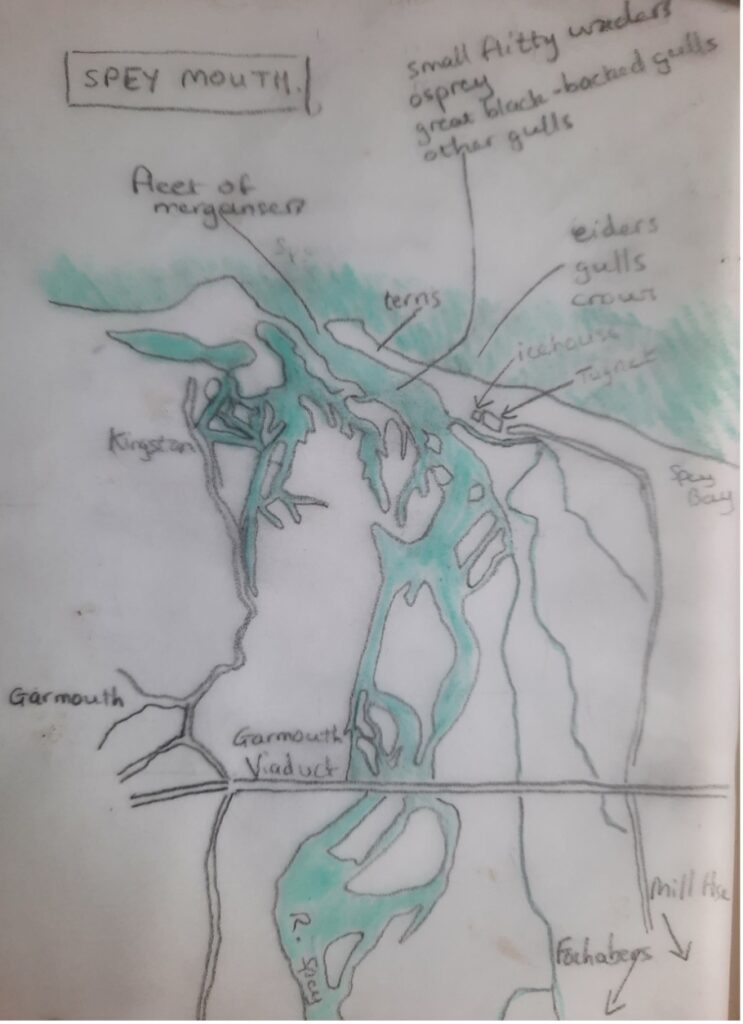

River mouth: Spey Bay

Day 4. On the last day at Ballintean we head outside to trace, draw and map. I trace the surroundings of Ballintean from the OS map – braided river, roads, forest – and add all our wildlife observations.

We spend a beautiful couple of hours back at the braided Feshie. (Is this the Feshie, or is that the Feshie? It’s all the Feshie.) I enjoy eddy dimples shedding off an exposed boulder and fish tail-like hazy green fronds flicking in the flow. All that complex motion – eddying surface, undulating weed fronds, river riffles – is mesmerising and satisfying. Today I am connected. There’s a small salmonid, impossible to say whether salmon or trout, nestled against its Favourite Rock. It’s still but with fast beating gills. How long will it patiently stay there and is it aware of being observed?

We drive off down the Spey. Satnav tries to persuade us to divert but we stick with the Speyside road for our journey to the river mouth. Spey Bay is at its finest in the sunshine. We wander up to the Garmouth viaduct, usually so magical, but it feels like we are all dragging our heels and yearning for the sea – we are heading in the wrong direction. We turn round and go out onto the shingle. Neil and I wonder what processes made and maintain this massive shingle bed; I suspect a combination of relict and active. We all feel this site is a world of danger for the smolts. How can they rush past all the hazards, like the fleet of sawbill ducks currently lurking in the river mouth, for their shot at marine life? When they smolt, are they aware of the dangers ahead?

[terns, osprey, eider, diver, greater black backed gulls, other gulls, a fleet of mergansers in the river mouth, small flitty waders, crows, orange tip butterflies]

Day 5. We meet again at Spey Bay, me with family in tow. We sit looking out at the narrow river mouth and wide sea and try to imagine the post-smolts’ ongoing journey – migration paths, cues, salinity gradients, shelf and shelf edge and beyond. The complexity and completeness of Spey Bay’s multifaceted environment, of our journey, are satisfying. And yet the journey is unfinished. How do we follow the salmon further?

As we leave Spey Bay, I realise that today I am attached and calm in a slow unphilosophical way. Later, I think about how the journey and life stages of the salmon are so varied in pace. Metabolism doesn’t always match with their pace of life. Eggs. Slow swelling, oxygen washed, stuck patient. Fry. Fast beating, rock attached. Parr. Station-holding, current-facing. Smolts. River racing, danger evading, urgent travelling. Post-smolts. Release seeking, frantic bursting out into salt water.