This text was written between 7th and 11th May 2024 as a group of artists and scientists followed salmon down the River Spey in Scotland.

1. Nursery

First activity

Moments of vitality

Possible futures

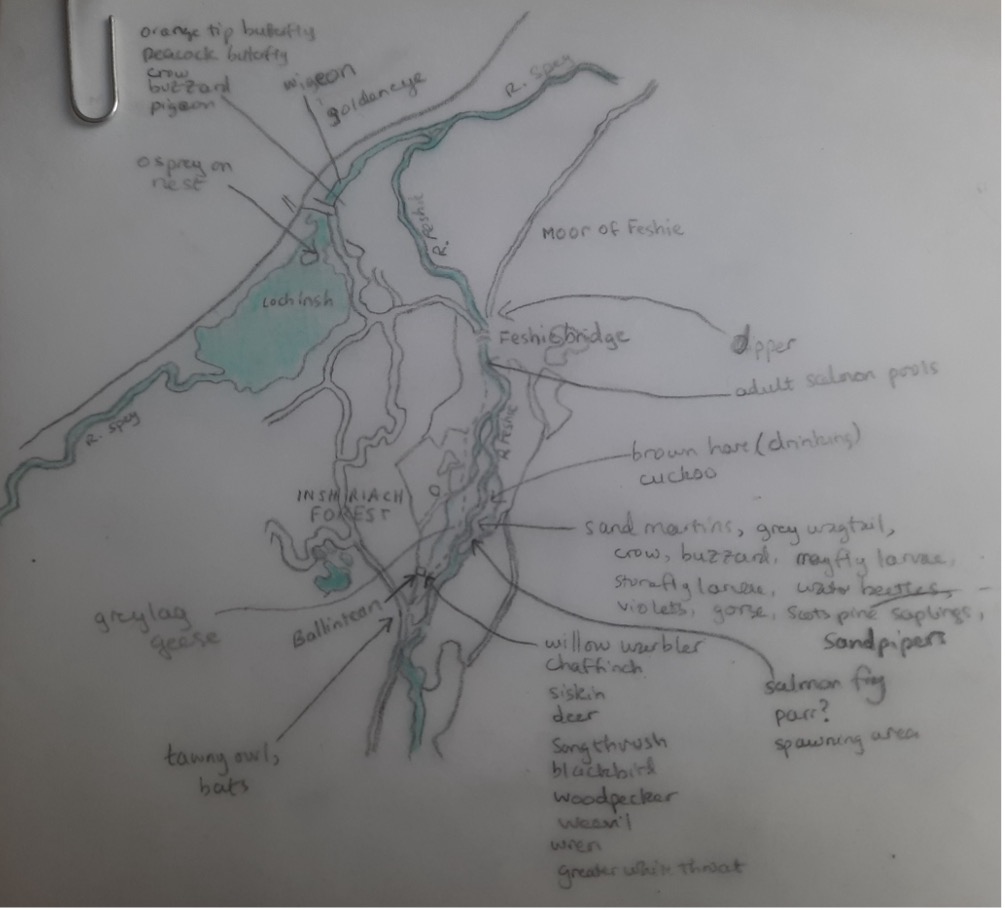

We are at Ballintean Mountain Lodge in the Cairngorms. An interdisciplinary collective, comprised of scientists, artists and artist-scientists, working together for the first time. For the next four days we will follow salmon as they make their first careful movements away from the redds – the matrix of eggs and gravel, where they have spent the winter. In these nurturing waters, the fry sense their environment from a place of stony sanctuary: moving up through the sediment as they seek the light. And, as the water warms in the springtime sunshine, they begin to tentatively look around, seek out new territories, and interact with their neighbours.

2. Refuge

The changing strata

Enclaves of time, for dwelling

Necessary space

The lodge and its grounds are immaculate. It takes time to bed in – to feel comfortable enough to sink into the upholstered sofas to sink into the deep, cold water and find space to hide. There is an alternative sense of time and place here: that which Michel Foucault called a heterotopia – a place, other. Other than the habitual routines of everyday life. How can we use this space? As we moved down the River Feshie, we encountered a radical shift in the waterway: from wide and dynamic to deep and constrained. This location is important for returning salmon. There is less of a surface for the sun to heat the water, so large, tired fish can wait down in the dark and the cold. Waiting for the right time to resume their homeward journey.

3. Holding Bays

Risky strategy

Suddenly changed behaviour

With no reference points

After an evening of introductions and exchanges, after a day or two of acclimatising and absorbing, there is a shift in our activity. I ask the group to create a response to the site or the salmon or the story-so-far. This feels like a different way of working, which is at once a small thing – a simple thing – but also a journey into unknown territories without the same way-markers or signposts. Loch Insh is small and poses fewer challenges than larger bodies of water. Nevertheless, in these places of pike and perch and trout, the newly silvered smolts are vulnerable. They will find safety in numbers, and shoaling behaviour begins. Weaving together experiences, movements, senses, words, ideas, hopes. We might get somewhere like this.

4. Flow

Real sense of movement

Just let the journey take place

And stop holding on

We are on our way now. Sometimes, we will be moved along in fast sections. There will be waterfalls, dams. They don’t turn and actively swim: they let the water take them. Sometimes, the river will move slower, and we will push on. What will that effort cost us? And along the way, we smolts – cryptic critters – will never stop feeding. Ingesting everything that we encounter as this flow moves us on. On towards wider, wilder waters. On towards salty seas. We will grow fat. We will travel vast distances. We will live through all this, only if we are very, very lucky. And then, one day, we will turn. And we will return. Over and over for as long as you will allow.

5. The Beat

Onto the highway

Something of a rhythm now

Nocturnal drifters

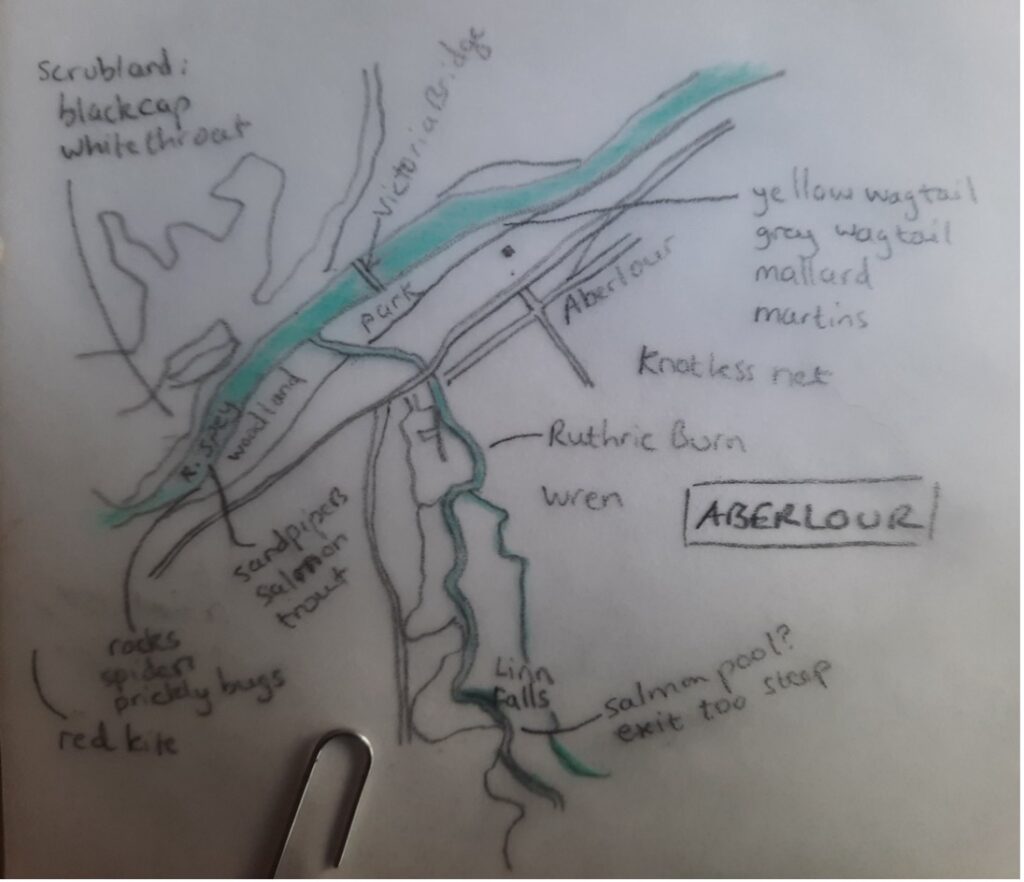

We are in a drastically different environment today. Moving downstream at varying paces, just as others (who are further on in their journeys) pass us, going the other way. Is there any interaction between the wee smolts and the sea-hardened veterans? A passing glance, perhaps? At this point in the river, the banks are fixed and manicured. Anglers’ nets hang at intervals; well-stocked huts for high-price spots. But this is not management of the waterway. It is riparian gardening. A little further up, where the water runs a little faster, unruly flora cling to natural islets and the pathway needs greater care and surer foot. Smolts and brown trout jostle for position, snatching the stonefly from the space between the elements.

6. Detour

A cul-de-sac turn

This can only go so far

Fall back to go on

Turning away from the Spey, we follow a new path as it winds through riverwoods to the falls. Here, the salmon drop back to spawn. They might make the initial leap, if they cared to attempt it. But the second would outdo them. Better to recognise the limits of our ambitions. Salmon have been known to travel miles, only to rethink, retreat – even past the salt wedge – to try another route. No point putting good money after bad. And after all this, if there is somewhere else that we want to go on to, something else that we want to achieve, then it might be helpful to remember that there are other ways to get there. There are other routes to take.

7. Estuary

Productive places

For those who survived this far

Silvery speed run

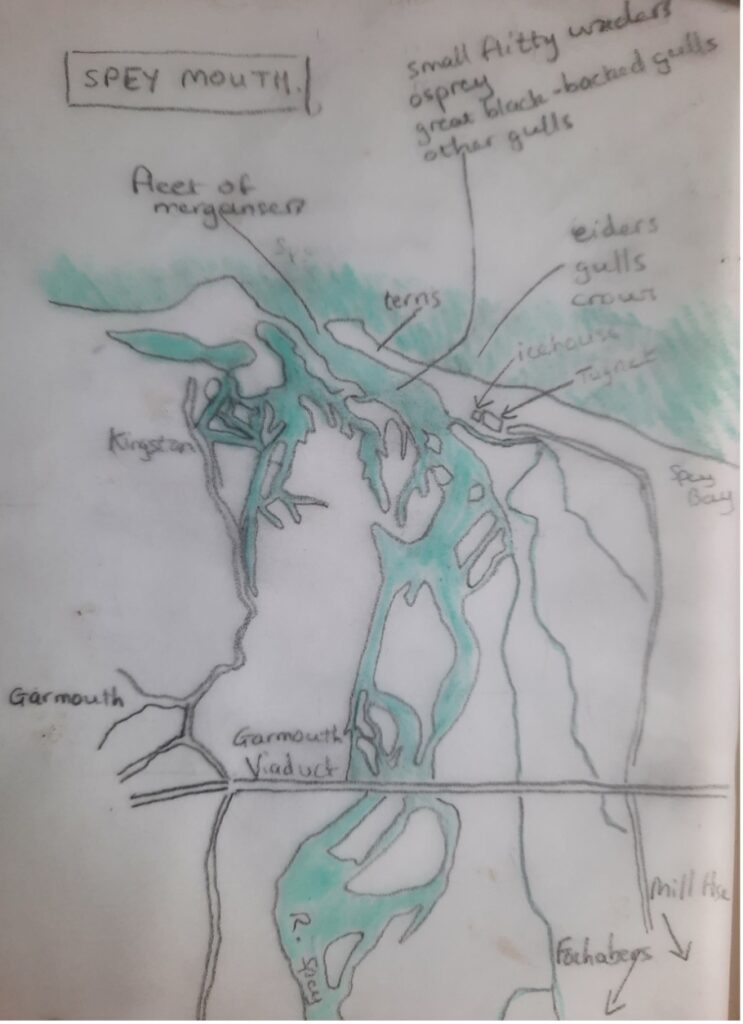

As they approach this threshold, up to 40% are lost. Three of our group have travelled south by the time we reach Spey Bay. An ecotone – a meeting point between two ecosystems – represented by the wedge of salt water that cuts underneath the fresh. As the winds and tides churn away, one world collapses into the other. The confident hold of the osprey, the oily squeak of the terns, the ostentatious landing of the swans. The smolts wait for the right time – the night time – to become post smolts. And they make a break for it, riding the ebbing tide and escaping their riverworld. Where will this trajectory take us?

8. Sea

A shift in scale, now

On past continental shelf

Futures possible

Actively swimming. Seeking deeper worlds and distant feeding grounds. Somewhere in the south Norwegian sea, at the edge of the shelf, others join the journey. From green to blue, Britain to Greenland. What are the reference points when we can only look out and imagine? How do we find our way? Currents affording speed and suggesting direction; river water slowly giving way to salinity; depth; magnetism. These piscine psychogeographers can follow flow. Can we flow with them?