Open Learning in Practice

This lecture looks at the global context of who produces, designs, shares and researches open educational practices, considering who they are for and who uses them. It will help you to prepare for the Week 10 Learning Fair.

Image: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 March 2017 Shift/Work (Neil Mulholland, Dan Brown, Jake Watts) Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Design: Andrew Gannon www.shift-work.org.uk

The aims of this course can be seen to be directly in line with those often associated with the educational turn, of widening access/broadening participation in art, aims that precede and exceed this ‘turn’ and relate and/or diverge with wider attempts historically and presently at widening participation in further and higher education globally through the expansion of open learning.

Who is ‘opening access’ and for whom? What is the context and in what ways is artistic learning closed/narrow that we would seek to broaden participation in it? What is artistic learning?

The impetus to create OERs and open models of education within the context of contemporary art and the educational turn can in part framed, as outlined below from The Curatorial Dictionary, as part of wider attempts to ‘democratise access to knowledge.’ We can see this desire for the ‘democratisation of access to knowledge’ in the university within Widening Participation departments, MOOCs, and Public Engagement programmes and the Edinburgh University’s Centre for Open Learning courses which are largely fee paying. Within galleries and museums we can see this manifest in the rise of public engagement programming and attempts to engage local communities, with some institutions trying to take on the role of ‘part gallery, part community centre, part academy.’ (See New Institutionalism) The activity of self organised art schools around the early 00’s could similarly be tied to this impetus.

Key concepts to unpick here are:

- Considering the difference between cultural democracy and democratization of culture/knowledge and where our own projects are coming from/going to.

- Cognitive justice. What knowledges are present/acknowledged/unacknowledged within the context we are operating in?

- Definitions of art and culture. What is our definition of art and culture, whose voices and what activities do we acknowledge under such terms?

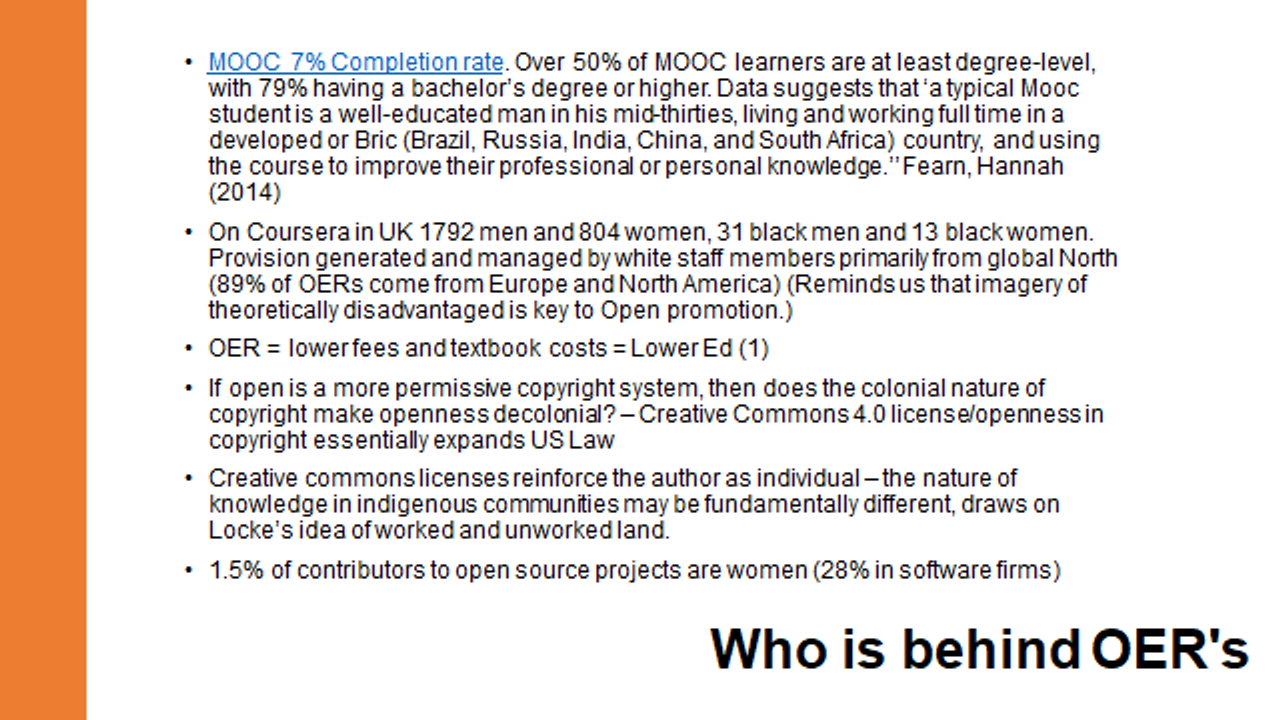

OERs and open forms of education tend to go for broad dissimentation as a strategy and ease of (digital) access.

In a similar way, public art institutions tend towards this strategy, counting their success based on audience figures and demographics.

Rogoff’s article ‘Turning’ covered in Week 1, frames access in the following way:

‘…I want to think about education not through the endless demands that are foisted on both culture and education to be accessible, to provide a simple entry point to complex ideas. The Tate Modern comes to mind as an example of how a museum can function as an entertainment machine that celebrates “critique lite.”

Instead, I want to think of education in terms of the places to which we have access. I understand this access as the ability to formulate one’s own questions, as opposed to simply answering those that are posed to you in the name of an open and participatory democratic process. After all, it is very clear that those who formulate the questions produce the playing field.’ (1)

How can this notion of access be put to work within in the context of contemporary art and the world at large?

What does this look like within the context you are working in?

And who is producing the playing field?

The most recent survey on social mobility in the arts in the UK can be found in the Panic survey. The Class Ceiling gives statistical evidence on who operates within the industry. The connection between the burgeoning activity associated with the educational turn and any advancement in the conditions it was trying to address for the wider population would be difficult to provide evidence for.

Anton Vidolke asks the above question in relation to this, Gregory Scholette warns that this activity risks of progservatism – a roster of socially progressive convictions is tethered to a foundation of managed economic conservatism, as does Andrea Fraser, where critical self-reflexivity in the arts = cultural capital.

The arts in particular face a unique challenge in shifting to the digital nature of education that is our new normal. Questions of how tacit knowledge is codified and shared and how we create useable, critical, dynamic OERs will be of increasing importance.

There are very few MOOCs available for contemporary art practice but they may become much more prevalant.

Being mindful of the inequality which already exists within the existing landscape of MOOCs and OERs is something to plan for in the arts rather than respond to.

Existing research has found the following above that some of the most sucessful open learning projects are those which ‘give equal attention to learning resources and group sociality (Coughlan, Perryman 2013). Indeed, the greatest challenge to Open Educational Practices (OEPs) effectiveness and potential in realising open education is underscored by COVID.

Most recently UNESCO produced a best practice guide on the use of OEP’s for teachers across schools to cope with Covid lockdowns (UNESCO 2020). The overwhelming emerging evidence suggests, the negative effects of this disruption has fallen to those who are already disadvantaged (Scottish Government 2020). We theoretically have the tools to pool common resources but barriers remain, indeed research suggests

‘OEPs can have negative effects where economic maldistribution exists’ (Bali et. al. 2020).

The question of access and social justice, which ideologically underpins OEPs, is thus imperative to address particularly for publically funded institutions.

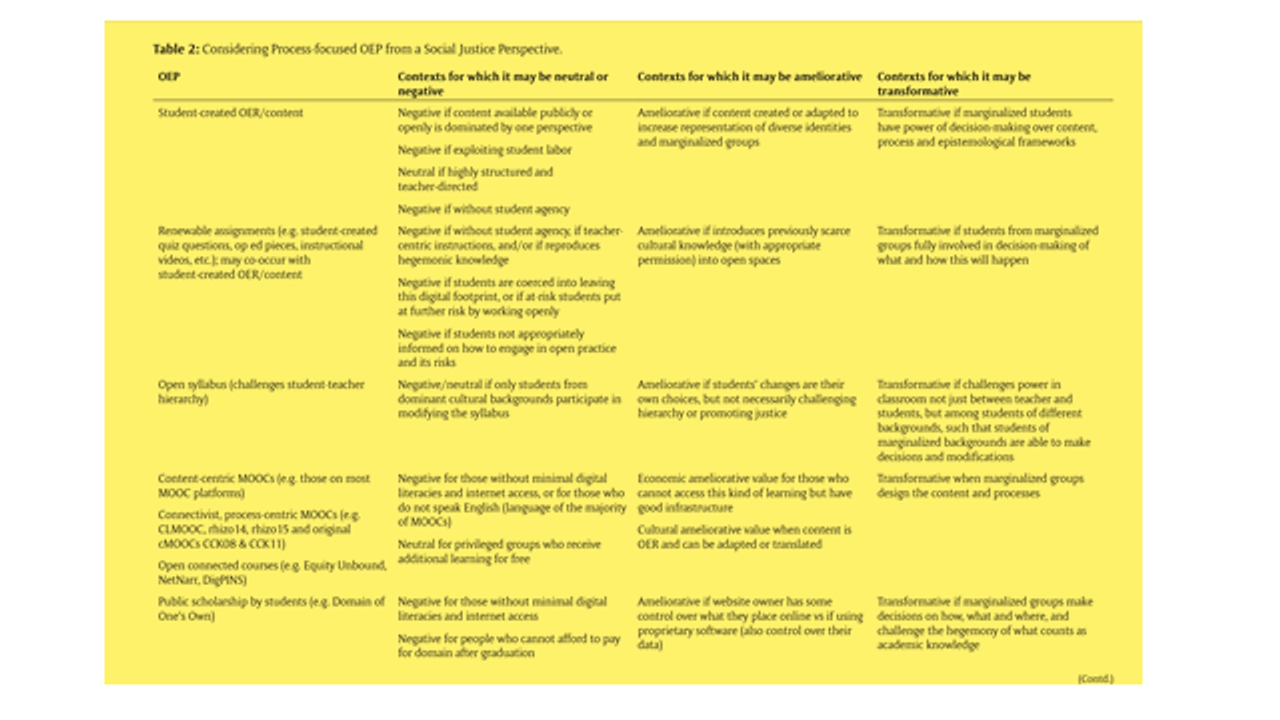

Such critical reflection is outweighed by ‘how to’s’ and documentation within existing research, but it is gaining traction. Bali et al use Hodgkinson-Williams and Trotter’s social justice framework to assess OEPs, while Adam’s highlights the lack of epistemic diversity in OEPs (Adam 2020), and Lee poses a pivotal question, ‘Who opens online distance education, to whom, and for what?’ (Lee 2020). This set of 3 tables above from Bali et al look at the ‘negative, neutral, ameliorative and transformative’ effects of open educational practices (Bali et al 2020) provides a way to think through improving practice in this field.

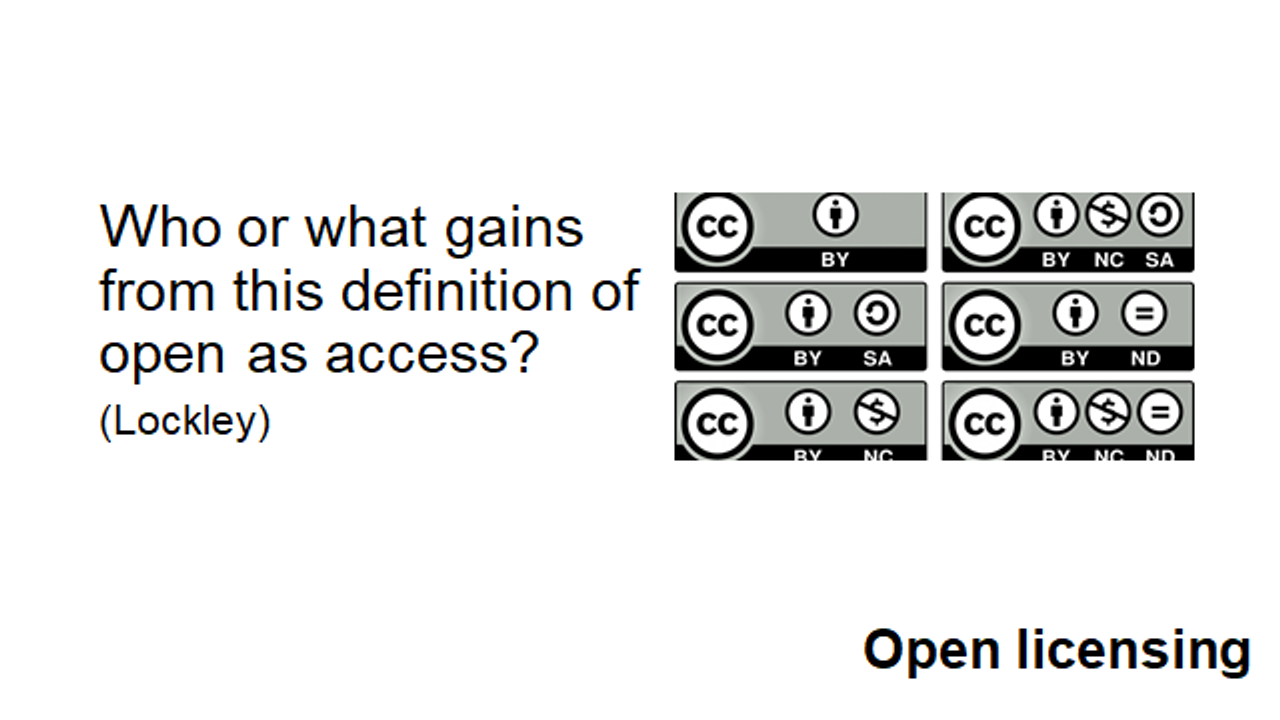

Lockely is clear about the consequences of the political or apolitical nature of openness here.

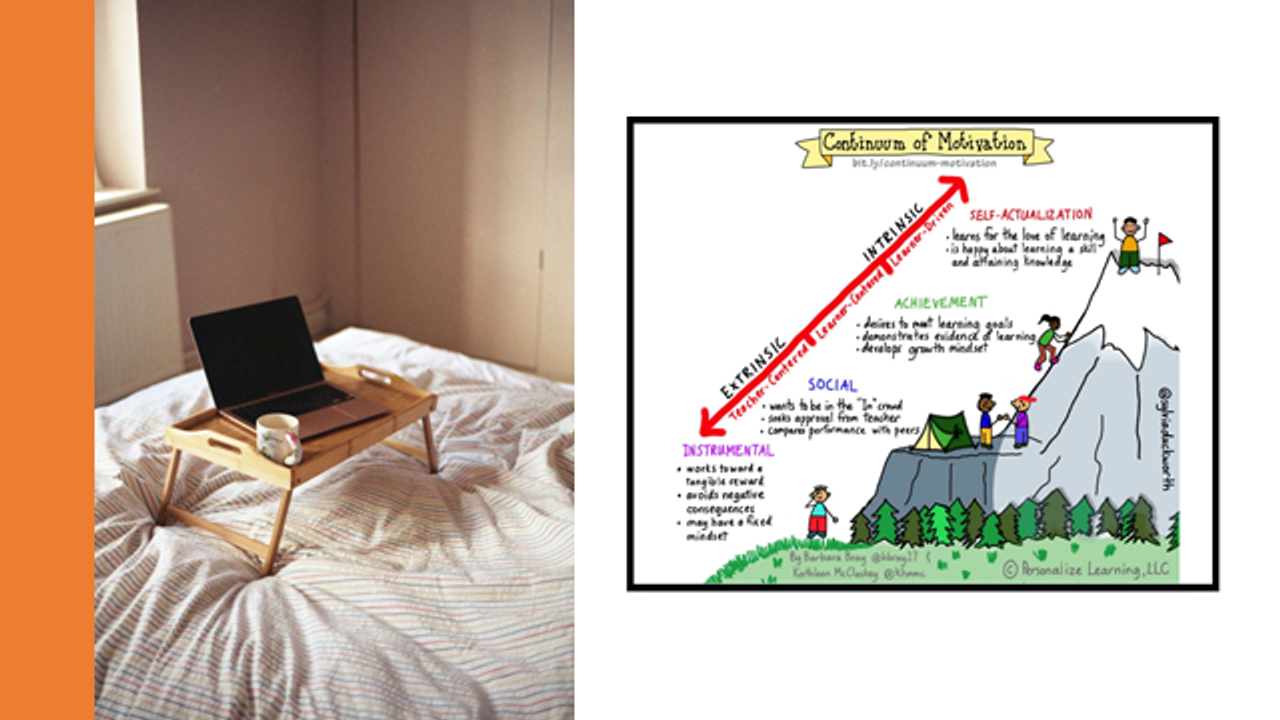

Critical reflection on underpinning theories of the subject and learning theories are less well developed in relation to OEP’s. While they draw from constructivist, critical and connectivist theories primarily, Knox (2014) provides a rare critique, specifically in relation to MOOCs, arguing that there is an underlying humanist assumption behind them, ‘the expectation of rational and self-directing individuals, with a universal desire for education’ Knox (2014). He develops a posthumanist reading of the open educational subject, one that must account for the human and non-human relation between the subject and the machine as they co-create the conditions for learning. He argues that the MOOC, and indeed the open resources produced by leading institutions only further ‘reinforces the distance and exclusion that it elsewhere claims to overcome’ Knox (2014) as there are those who are within the university, and those who are outside. Furthermore, he asks ’The productive question that might then be asked, is not what the elite educational institution can do for a universal population in deficit (via OERs), but how the diversity of global participation can change the very idea of the university’ (Knox 2014b). More recently, Havemann et al (2020) develop a theory of ‘open educators’ using threshold concepts applied to the development of OEPs.

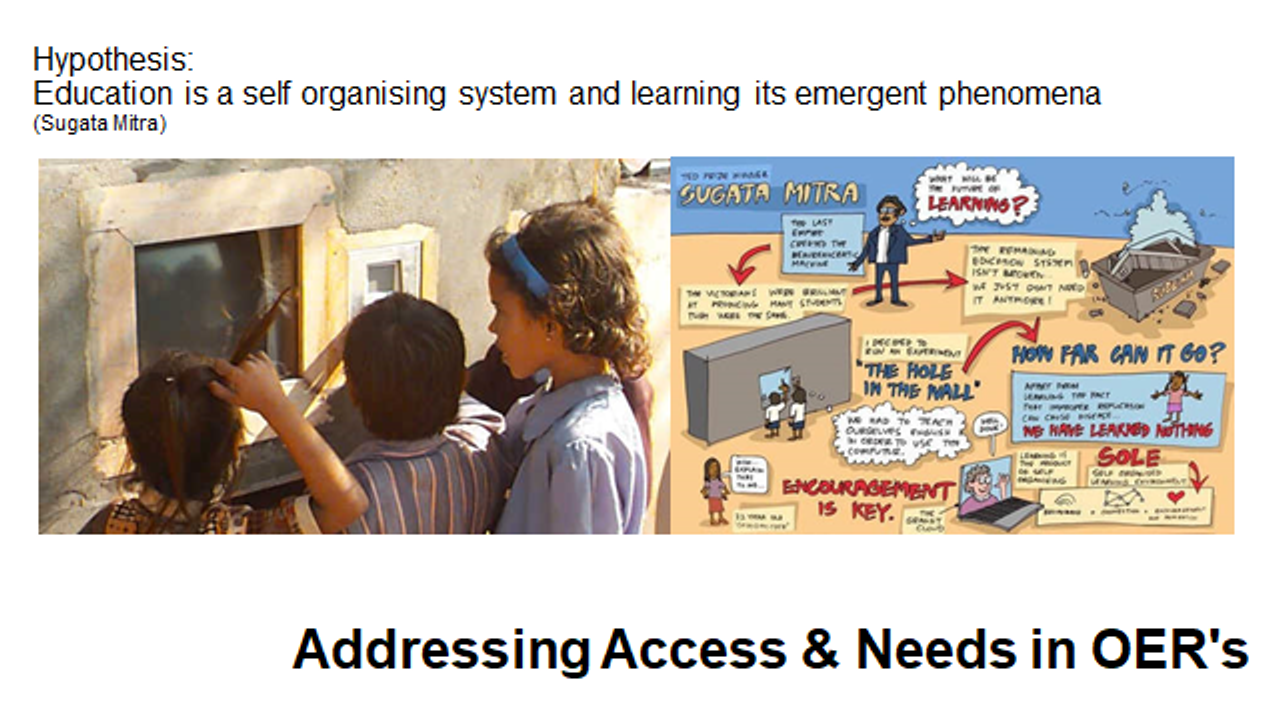

What examples might we turn to that do specifically attempt to turn these advances in open education to those most in need? While the project inevitably had it’s pitfalls, Sugata Mitra’s Hole in the Wall experiment which occupied him for over a decade is an example of a committed attempt to democratize access to knowledge. Mitra presented the hypothesis that ‘education is a self organising system and learning its emergent phenomena’ and went about testing it by placing computers around slums in India. Through his research, he found that children taught themselves their way around the computer and utilised to learn a range of subjects. He went on to focus on the role of encouragement within this as something that emerged as key within the learning process and so set up the ‘Granny Cloud.’ (School in the cloud) Many of the computers Mitra’s project left in slums have fallen into disrepair or are dominated by boys however, following this project from inception, to dissemination, tweaking/modifying/and their current or afterlife.

Some examples of OERs that have designed for their ‘who’ in different ways/to different levels of success:

Art History Teaching Resources

Also worth a look is The Experimental Publishing master course (XPUB) at Piet Zwart which ‘focuses on the acts of making things public and creating publics in the age of post-digital networks.’

To end, how does open learning feature in your life, what really works for you, that you feel able to use and access easily, what enables and supports this, notice the design, language, distribution, and how these forms anticipate you as a user.

And to recap existing research on OEPs overwhelmingly focus on practicalities of producing and sharing the products of OEPs, asking ‘how might we do this’ as opposed to ‘who is this benefiting?’ The tendency for these new tools has been an impetus to primarily generate content. Nearly a decade on, however, it is time for such projects to ask these key questions from their inception and share these reflections: What is your definition of OEP? Who is this process/resource for? How will it be designed with those users in mind and/or a neurodiverse public body in mind? What is your overall aim? How does this method align with your aim? (Following Boshears….) what public is it generating and what might it generate?