What Am I Looking At? – Week 2

![A salesperson, naps in a tech startup's office on April 15, 2022. Once busy with sales calls, tech conferences, and trade shows that frequently took her around the country, she has plenty of downtime. Changzhou has strict quarantine policies for residents who leave the city and return, making business trips unpopular. [photo by Theresa Boersma] Woman facing away from the camera, sprawled across her computer desk as if sleeping. Behind her, through a half-unshaded window, you can see a multi-story pagoda](https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/ls_efie11121_efie11122_2022_23/wp-content/uploads/sites/6900/2022/10/Boersma-Final-3May2022-12-scaled.jpg)

Last week, I ran across this thread on Twitter.

I wanna zoom in on one word in one sentence. “There is a *need* to develop a system that establishes a link between spoken and sign languages.”

This entire abstract and paper are obviously wrong and deeply problematic, but let’s talk about “need” for a moment. https://t.co/LdzCZXrZle

— Zeerak Talat is on the job market (@ZeerakTalat) September 29, 2022

Zeerak Talat is a post-doctoral fellow at the Digital Democracies Institute at Simon Fraser University where he researches and critiques machine learning and how it works to marginalize people. In this thread, he briefly breaks down problems in a conference paper that claims: “There is a need to develop a system that establishes a link between spoken and sign languages.” He takes issue with the word “need” and asks how much of a “need” really exists for a piece of software that can translate between signed and spoken language. It’s a quick and thoughtful read, and relates back to the article I posted last week on AI being integrated into a factory workshop that employs people with disabilities to help them improve their production quotas.

In the case of the workshop that trains and employs workers with disabilities, it’s up against the hurdle that manufacturing emphasizes the cheapest production methods that can pass required quality standards (even in a corporate world paying lip service to ESG, profit still reigns in the global economy). While there are some tax incentives in China for companies that hire workers with disabilities, typically companies don’t involve those workers in production, citing stereotypes about what people with disabilities are able to do. Instead, they often place them in lower-paid janitorial positions. If you are able to use AI to bring down the overall costs that can come with training and managing production line workers with disabilities, then this makes hiring them more tempting to companies. Is there, then, a need for such technology?

Contrast that with the paper Talat is addressing about using AI to turn sign language into something intelligible to those who don’t understand sign language (and ignoring the other many problematic assumptions that come up in just the abstract). Given that we have developed other technologies that are universally used by both hearing and non-hearing communicators (i.e. written languages), is there an actual “need” for this outside the realm of perhaps encouraging more people to learn sign language? And does that “need” trump the tendency for technologies like this to wind up in surveillance and censorship systems (like this example of Chinese companies censoring Uyghur and Tibetan languages)?

Data is always tempting to create given what we now know about how powerful using it can be but are there instances in which it’s better to not capture it?

Shifting Gears: A Neat Data Instance

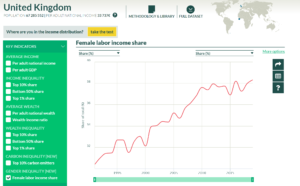

I was playing around with the World Inequality Database ( WID.world ) this week as part of my dataset explorations for Exclusion and Inequality, which dropped me down quite the rabbit hole. Here’s the graph that did it:

The share of female labor income in China [source: WID.world]

- Brazil

- India

- Japan

- Germany

- United Kingdom

- United States

Do you see it?

In most countries around the world, the trend is for women to earn a larger share of labor income as time goes on. There are really very few countries (mostly former “Eastern Bloc” countries like Lithuania, Russia, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia) where this is not the case. It’s so unusual, that Theresa Neef and Anne-Sophie Robilliard at the World Inequality Lab addressed it several times last year in the paper they produced on the dataset. They never reached a conclusion on the downward slide.

China’s gender gap is also a phenomenon that others have noticed. As I was googling around, I found more articles that talk about gender inequality in China, including some linking it to discrimination in the workplace.

The Peterson Institute for International Economics believes gender discrimination is “dragging China’s growth,” which CNBC picked up on and further fleshed out with additional reports.

Workplace discrimination is a problem for women in China. But it’s also a problem for women the world over, and I don’t buy that discrimination is increasing so much in China that it’s causing the percentage of labor income earned by women across the country to decrease when it’s increasing throughout the majority of the rest of the world. While Chinese society does tend to follow pretty conservative ideas when it comes to gender roles, I’ve lived in China for over a decade, and I just don’t feel it’s getting more conservative and discriminatory.

At one point Neef and Robilliard posit that perhaps the relaxation of China’s infamous “one-child policy” into a “two-child” policy in 2013 could play into the downward trend (more kids make it harder to work full-time). But when I downloaded all the data from WID and fed it into Excel, the chart I built actually shallows out a little bit after 2013, which would suggest that the downward trend decelerated slightly after the “one-child policy” relaxed.

Another idea Neef and Robilliard suggest is that the downsizing of China’s SOEs (state-owned enterprises) could play into the slide, with women moving from stable employment in SOEs to less stable private enterprises. This possibility opens up a lot of other interesting lines of inquiry as well. I think the education sector, for example, could be another point to look into. China’s families have long prioritized education, and as wages strengthened over the last few decades, a lot of money went into private afterschool tutoring and private K-12 schools that boasted of getting students higher scores on the gaokao, China’s high school exit/college entrance exam. Over the years, the trend has been for extra classes to become all-consuming with mothers often ending up the parent tasked with hauling children to their full slate of extra-curricular classes.

The WID data only goes up to 2019, after which point things got really wacky in China with the pandemic causing massive upheavals in labor (when cities reopen after sudden lockdowns—that can last days, weeks, or months—schools are usually the last to let students and staff return, which sticks families in awkward situations as often only one parent can return to work, leaving the other to juggle childcare with working from home for several weeks—a role that most frequently falls on “mom”). On top of this, last year, there was a huge crackdown on the private education sector in an attempt to make it less of a burden on families after China announced a further relaxation of the “two-child” policy to a “three-child” policy and exhausted Chinese families responded by collectively rolling their eyes and saying, “No, thank you.” In the aftermath, many companies were forced to close in a sector that skews female, leaving many out of the job, and schools were told to stay open longer to fill the gap (potentially dumping the burden of additional child-minding roles on already overburdened teachers, who also skew female).

Of course, there is also the possibility that, given the priority that a child’s education can be for a family and given that incomes have risen dramatically over the past few decades, once parents’ incomes have reached a point that one income can cover a family’s expenses, the other parent might choose to lessen their work burden by moving into a part-time position to focus more attention and time on the child’s education.

So that’s a lot of words to say, I think there are possibilities for fascinating things that could be explored here.

Recent comments