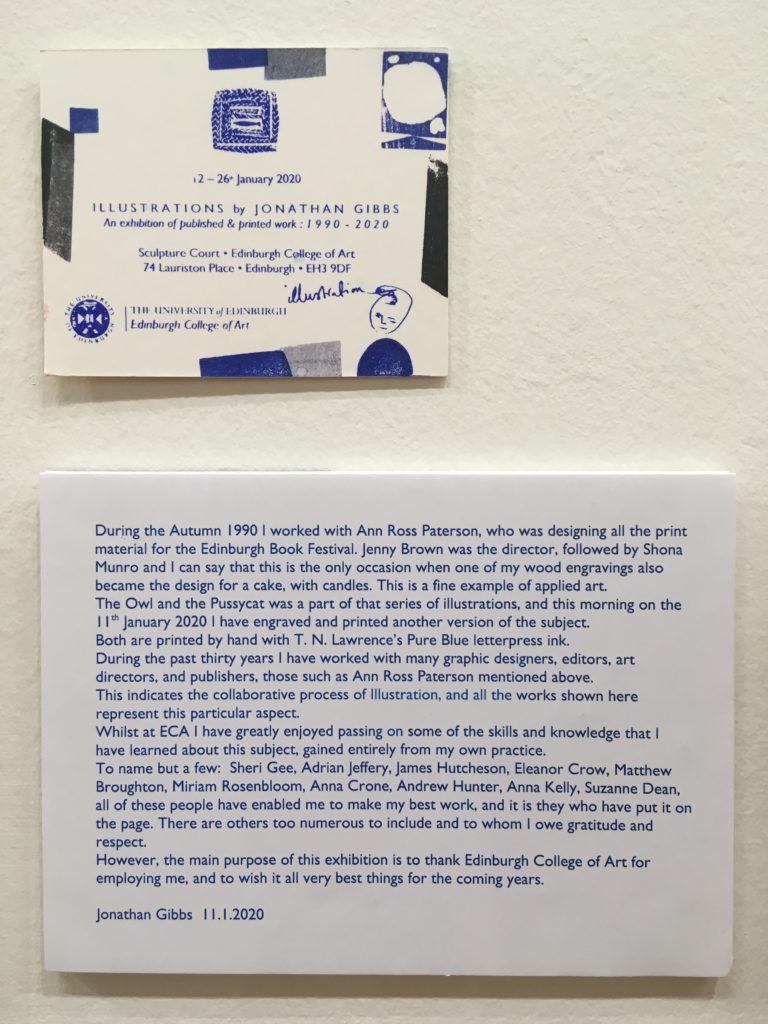

During January 2020 there was an exhibition at the Open Eye Gallery entitled Paintings, Drawings, & Wood Engravings and a parallel event showing of Illustrations by Jonathan Gibbs at the Edinburgh College of Art.

These connected two aspects of theory and practice in my art-work. This is only significant because they also mark the juncture of my retirement from the University of Edinburgh.

I have exhibited at the Open Eye since 1985 and began working at ECA in September 1990.

There is a close relationship, separation, and a conflict between the hand-made and reproduced character of my work.

It is a natural division, I suggest, resulting divergent career paths within art & design.

However, it is a close relationship, with overlaps and ambiguities of purpose.

This is partly conceptual and aesthetic as well as something that gives creative energy and impetus for related kinds of work.

*

Paintings, Drawings, and Wood Engravings at the Open Eye included current and retrospective pieces.

These seventy-two works were made by different means: woodblock printmaking; gesso and oil paint on wood; graphite, charcoal, ink and pencil on paper.

This hand-made aspect has always been crucial to the visual expression of my ideas.

It has always given me great fulfilment with its roots established during art school studies, school-days and childhood.

Amongst these artworks there is pure abstraction as well representational image-making.

Within such idioms there is an exploration of the harmonic relationships of line, colour, tone, and form.

Abstraction and representation express aspects of pictorial space, illusion, and the nature of surface in an exploration of particular subjects. Usually these are landscape, still life and organic forms. There is an underlying discipline of observational drawing as well as imaginative image-making.

*

Literary subjects and pictorial narratives were also exhibited at the Open Eye, in alphabet illustrations; natural history subjects and visual responses to T. S. Eliot’s poetry.

Coming at the close of a full-time teaching post, this was an opportunity to appraise artistic identities in different kinds of work.

Questions arise, such as what is the value of a reproduced image as opposed to that of a unique image?

This is to say, what is its artistic, cultural or philosophical worth as well as its monetary value? I used to worry about such distinctions, almost from an ethical point of view, but do so no longer. However, illustrations are intended for reproduction in multiple formats, usually, so this is a pertinent question. In London, the Chris Beetles Gallery and Illustration Cupboard sell original artwork by illustrators. It is possible to buy an original pen and ink drawing by Ernest Shepard or Quentin Blake and the Tate Gallery owns original artworks by Beatrix Potter. These watercolours have more value than the actual Peter Rabbit books.

*

The Open Eye Gallery directors also curated an adjacent exhibition by ECA alumni.

These are artists and designers whom it was my privilege to teach at various points since 1990. In tribute to this connection, I included three drawings I had made during my own studies at the Central School of Art & Design and the Slade School of Fine Art. These demonstrate my formal interests and subject matter that have remained more or less consistent to the present.

*

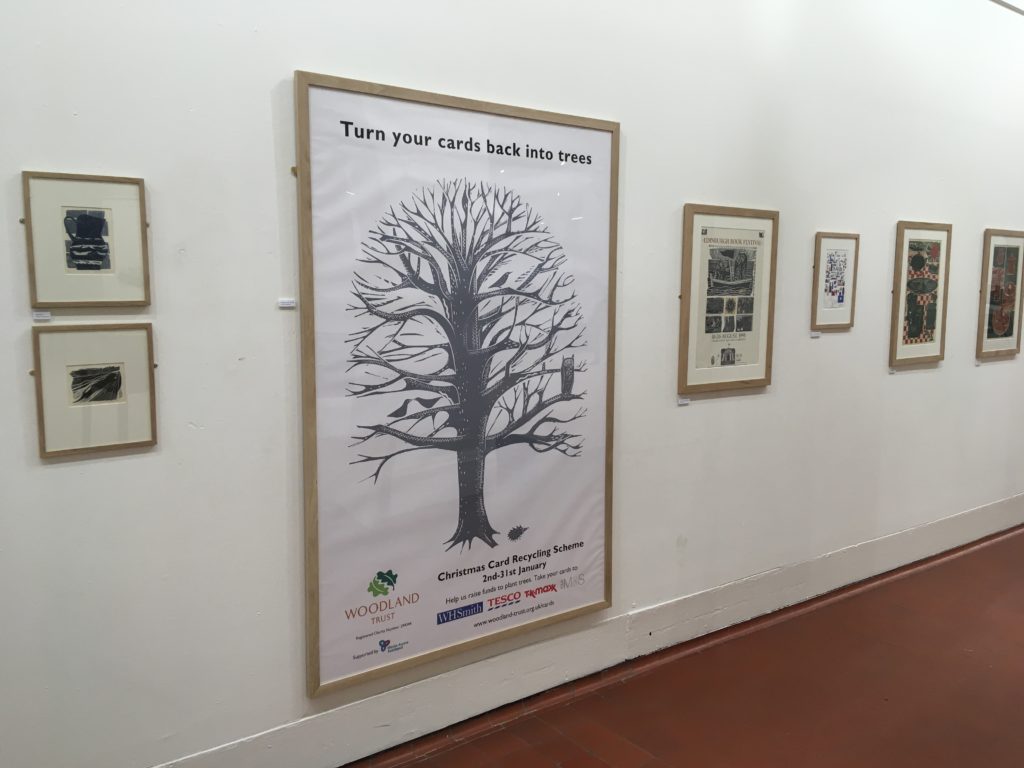

On the other hand, the works exhibited in Illustrations by Jonathan Gibbs at the Edinburgh College of Art in entirely consists of printed reproductions. There were two exceptions: Kitchen Interior, Greece, a pencil drawing dedicated to James Campbell, a ceramicist recently deceased, and Life is but a dream, a large-scale woodcut.

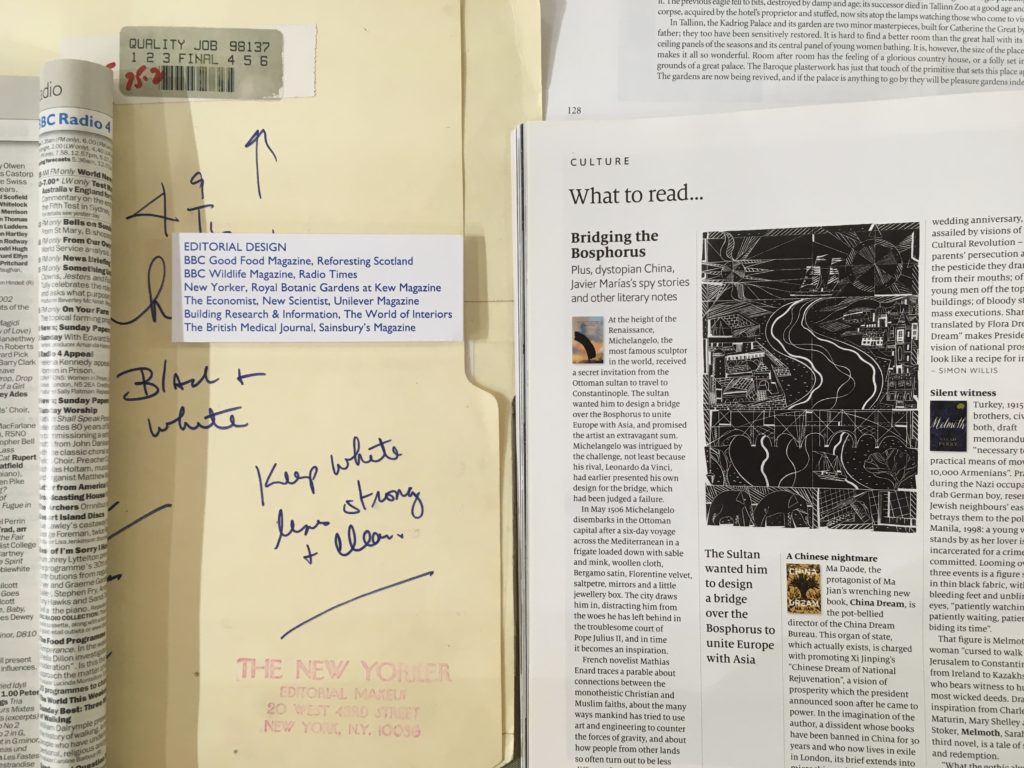

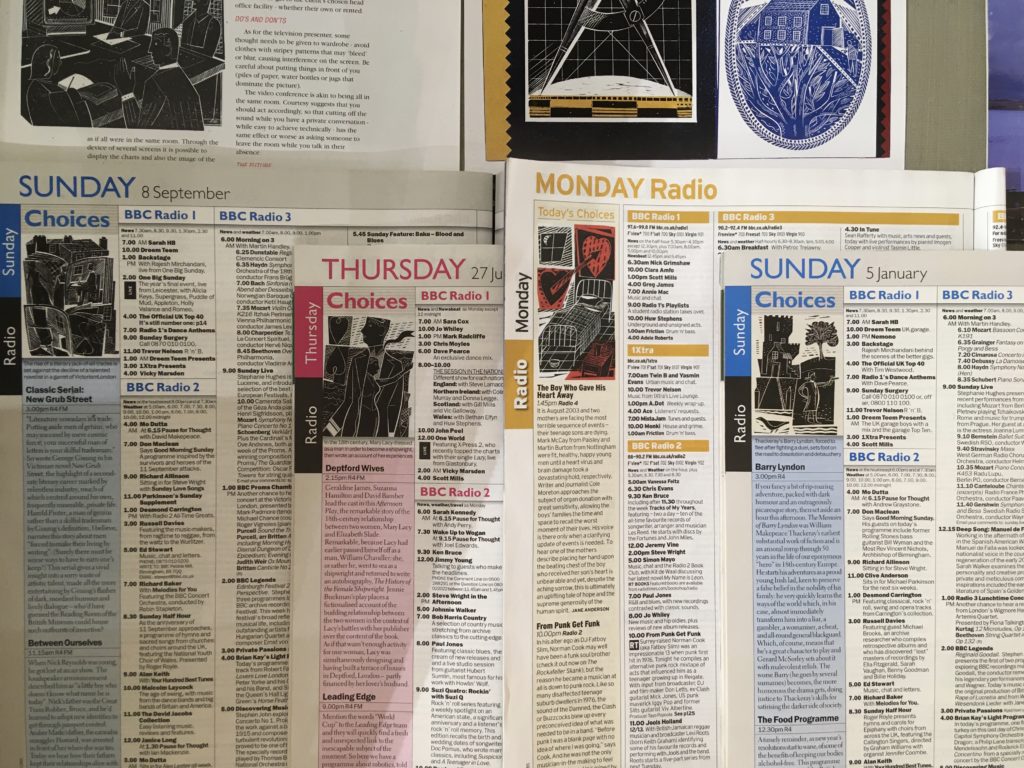

All the illustrations were commercially printed and published and each piece is one of many identical copies from the print-run.

All the wood engravings were digitally scanned in my studio on an A4 Canonscan Lide 600F.

Otherwise, I used the A3 Epson Scanner in the ECA Art & Design Library ECA during lunch-time or at the end of a working day. It is an excellent scanner.

Earlier works for Canongate, for example, were made into photographic transparencies for the printing process.

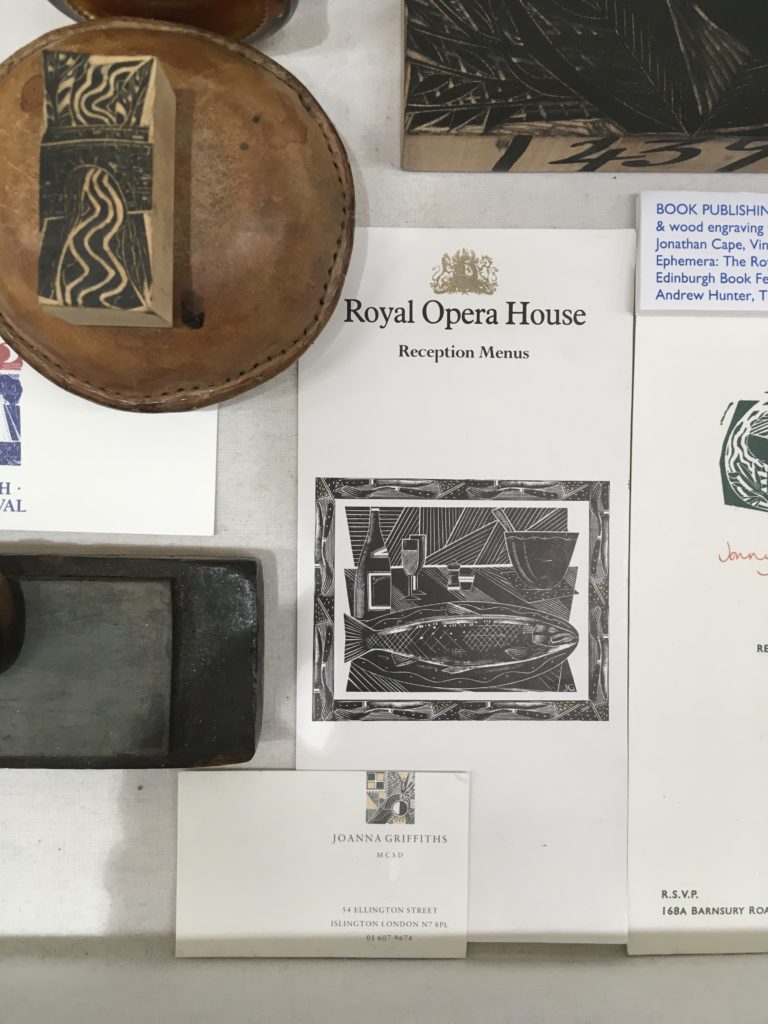

In each case I was paid for the use of the image and retain all the original artwork and its copyright. Second usage of any illustration elicits a second fee. This leads to the other significant aspect of the ECA exhibition: all of the work was commissioned.

None is authorial or self-initiated, and all is made collaboratively with art directors, publishers, agents, editors, and printers. The ECA exhibition paid grateful tribute to these people.

The Radio Times circulates 750,000 copies per week, and the Folio Society publishes 60,000 copies of a book. The Guardian and World of Interiors, or the Economist, all publish in excess of 250,000 copies, and so on. To an extent, the value or impact of such work lies in its multiplicity in which it has a wide and diverse reach of communication.

Although illustration has often been described as commercial art, I maintain that the creation of such imagery employs knowledge, conceptual thinking and skills used by most artists, whether they practice within the fine or applied arts.

During my time teaching at the Edinburgh College of Art there have been few exhibitions of published illustration in the Sculpture Court. However, the AOI annual Images exhibition was occasionally shown in the Andrew Grant Gallery in earlier years.

At this conclusion, I have made connections between so-called conflicting contexts of artwork exhibited at the Open Eye Gallery and the Sculpture Court in Edinburgh of Art in January 2020.

These two events represent a thirty-year period within a working life.

All of the art work originated as wood engravings, with very occasional elements of woodcut and hand drawing. The giant woodcut resulted from my 2017 sabbatical research project about rivers and it was first exhibited the at the Open Eye Gallery in 2018.

Jonathan Gibbs

April 2020