Introduction and Context

Universities in the UK have been aware of the prevalence of attainment gaps between various demographic groups since the 1990s, with differences in degree attainment first noted between ethnicity groupings (Connor et al. , 1996). Since then, they have become a focus for research, policy, and institutional strategies. The University of Edinburgh has persistent attainment gaps across ethnicity, gender, disability, and age. Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic students, male students, disabled students, and students with age on entry 17 or under and aged 21 or over have been awarded lower degree classifications historically.

A lack of anonymity in assessment was posited as a contributing factor to these attainment gaps, with systemic bias and prejudice potentially causing markers to award marginalised students lower marks. This suspicion led to 2008 campaign by the National Union for Students “Mark my words, not my name”. At this time, students and student unions were concerned bias and discrimination had an impact on the way their work was assessed, leading to research connecting anonymity with the long-established attainment gap challenge in Higher Education (National Union for Students, 2008). Following this campaign, many UK universities adopted regulations which required anonymity where possible.

Yet attainment gaps persist across the sector, despite the anonymity requirement. Research has since contested the claim that non-anonymous marking leads to bias, potentially offering understanding behind the prevalence of the gap, despite the adoption of anonymity (Pitt and Winstone, 2018; Whitelegg, 2015). Additionally, in recent years the attainment gap has shown male students, not female, obtain lower marks. National Union for Students description of systemic prejudice in non-anonymous marking described this primarily impacting female students, but this is not necessarily the case currently.

However, there is a large gap in the research connecting anonymity and attainment gaps: learning technology has not yet factored into these discussions. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, learning is conducted increasingly online, and most universities in the UK require assessment to be uploaded and feedback released through a Virtual Learning Environment (VLE). This environment offers many new avenues of discussion in the equality and diversity sector, with considerations surrounding web accessibility, digital capability, and now Artificial Intelligence (AI) entering conversations.

One specific aspect of this learning technology that relates to assessment and feedback is the use of dropboxes. Students submit their work in the VLE through dropboxes, to be marked anonymously by course tutors. At least, this has always been the assumption. Research done as part of the University of Edinburgh’s LOUISA project (Learn Optimised for In-course Assessment and Feedback) found that many Schools and Deaneries at Edinburgh have a different approach, with some using one dropbox, and others using two (one for on-time submissions, the other for late submissions or those with extensions). In instances where Schools use only one dropbox, it was found that submissions received after the deadline may be de-anonymised when on-time marks and feedback are released. Due to the large number of late submissions, extensions, and special circumstances seen at the institution, this inconsistency may impact a large number of students, affect previous assumptions on the anonymity of marking, and thus its relation to the attainment gap.

This preliminary study explores the relationship between these learning technology decisions, attainment gaps, and anonymity through a case study at the University of Edinburgh.

Research question

Past understandings of the impact of anonymity on the attainment gap in the higher education context have not considered the potential variation caused by School-level learning technology decisions. The main objective of this study was to understand the role dropbox usage may have on the relationship between attainment gaps and anonymity, and contribute to the debate through a new, learning technology lens. With the understanding that one dropbox makes it difficult to ensure anonymity in assessment, the main research question answered in this review is:

“Does the number of dropboxes decided on at a School-level have a relationship with the attainment gap?”

The aim was therefore to explore if one-dropbox Schools, where anonymity may not always be preserved, had a stronger relationship with attainment gaps.

Methodology

The dataset was drawn from administrative data held by the institution on attainment gaps by School, in the Annual Monitoring Report provided by Student Analytics, Insights and Modelling in Registry Services. Snapshot data was gathered as part of a University’s LOUISA project, showing dropbox use across Schools and Deaneries at the University of Edinburgh in the academic year 2023-24, with these decisions being implemented at a School-level and impacting every course.

The study notes the potential for course-level exceptions in dropbox number, but recognises this was likely a very small proportion, with the majority of courses likely aligning with the School-level position. Table 1 depicts the results of this analysis. Schools with “Other” numbers of dropboxes involved either more than two dropboxes, or dropbox use varied significantly in the School. The former is theoretically similar to the two dropbox workflow, with the additional dropboxes often hidden from students. However, they were excluded from the study to avoid misinterpretations. The latter would be too difficult to consistently predict without course-level analysis, and so was also excluded.

To explore as wide a range of data as possible, all three attainment gap metrics available in the institutional data were explored. These were:

- Course Pass Rate (%)

- Average Course Mark (%)

- High Classification Award (%)

The latter is the most common metric included in attainment gap discussions, so correlations and boxplots in the following section are for High Classification Award. This study explored these metrics for gender and ethnicity only, with disability and age excluded for various reasons, including variation in sample size across characteristic.

Boxplots were created comparing the three metrics across characteristic (for example, male and female students) and School (grouped into one and two dropboxes). Point-biserial correlation tests were run to explore if the number of dropboxes had a relationship with the attainment gap, across characteristic. For example, if the correlation was positive, but smaller for white students than BAME, then this indicates two dropbox Schools (with anonymity) had a greater, more positive impact on BAME students than white.

Findings

Gender

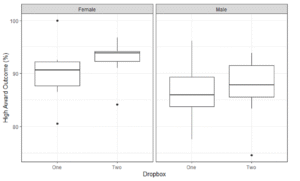

Both male and female students had higher degree award outcomes in the two-dropbox Schools. Figure 1 shows female students had less overlap between one and two-dropbox Schools than male, with the mean award outcome in one-dropbox Schools 90% for female students and 87% for male. In two dropbox Schools, this gap widens to 93% for female and 87% for male.

Correlations were 0.24 for female students and 0.06 for male, showing a larger increase in award outcomes in two dropbox Schools for female students. This was the largest correlation gap, at 0.19, however female student performance increased more significantly with two dropboxes across all three metrics.

Note, the gender attainment gap shows male students perform worse across the three metrics, so an increase in female performance would actually widen the gap. However, early National Union for Students research (2008) found anonymous assessment was more beneficial for female students, as upheld by this preliminary research, and not a contributing factor to male student under-performance.

Ethnicity

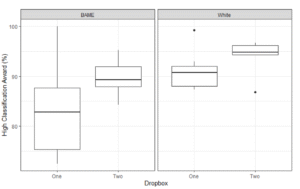

Both BAME and white students had higher award outcomes in two-dropbox Schools. Figure 2 shows a greater spread of High Classification Award proportions for BAME students in one-dropbox Schools, with the mean award outcomes at 83%. This was 91% for white students in one-dropbox Schools. In two-dropbox Schools, mean outcomes were 90% for BAME students and 94% for white.

Correlations were 0.42 for BAME students and 0.38 for white. However the largest correlation difference was for Course Pass Rate, at 0.10. Again, these results could indicate BAME student award outcomes improved in two-dropbox Schools at a larger rate compared to white students.

Summary and Limitations

The overall correlations between dropbox number and the three metrics were quite small. This was expected, with there being little indication that one or two-dropbox Schools would have differing award outcomes. However, there were some significant differences in correlation between characteristics, for example, 0.24 for female students and 0.06 for male. This indicates there was a much stronger impact of two dropboxes on award outcomes for female students than male.

The statistical significance of correlation differences such as these largely depends on sample size. The sample size for this introductory research was relatively small, as it contained only one year of data. Future research could investigate past dropbox use in Schools, and create a historic dataset to examine trends overtime, to make conclusions stronger.

These preliminary findings show that there is a relationship between dropbox number and attainment gaps, indicating the inclusion of learning technology in conversations about anonymity and attainment gaps may provide further understanding to many of the debates. It provides evidence of the importance of local learning technology decisions on impacting sector-wide equality and diversity challenges, and thus strategic planning at an executive level in the institution. Although not a comprehensive study, this preliminary research solidifies the need for broad perspectives when combating historic equality and diversity issues, and creativity in exploring speciously small decisions, when they can in fact have potentially long-lasting ramifications on student outcomes and attainment gaps.

References

Borkin, H. (2020). Locating bias in higher education marking practices, Locating bias in higher education marking practices | Advance HE. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/locating-bias-higher-education-marking-practices [Accessed: 26 August 2025].

Connor, H. La Ville, I., Tackey, N. & Perryman, S. (1996). Ethnic minority graduates: Differences by degrees. Available from:

https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/309.pdf [Accessed 26 August 2025]

National Union of Students. (2008). Mark My Words, Not My Name: The Campaign for Anonymous Marking. Available at: http://samairaanjum.weebly.com/uploads/1/0/5/2/10526755/markmywordsbrief1-1.pdf [Accessed: 26 August 2025].

Pitt, E. and Winstone, N. (2018). ‘The impact of anonymous marking on students’ perceptions of fairness, feedback and relationships with lecturers’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(7), pp. 1183–1193. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1437594.

Stonewall, J. et al. (2018). ‘A review of bias in peer assessment’, 2018 CoNECD – The Collaborative Network for Engineering and Computing Diversity Conference Proceedings [Preprint]. doi:10.18260/1-2–29510.

Whitelegg, D. (2015). ‘Breaking the feedback loop: problems with anonymous assessment’, Planet, 5(1), pp. 7-8. https://doi.org/10.11120/plan.2002.00050007.