How do I decide when to adapt and when to speak up? What are the risks and costs?

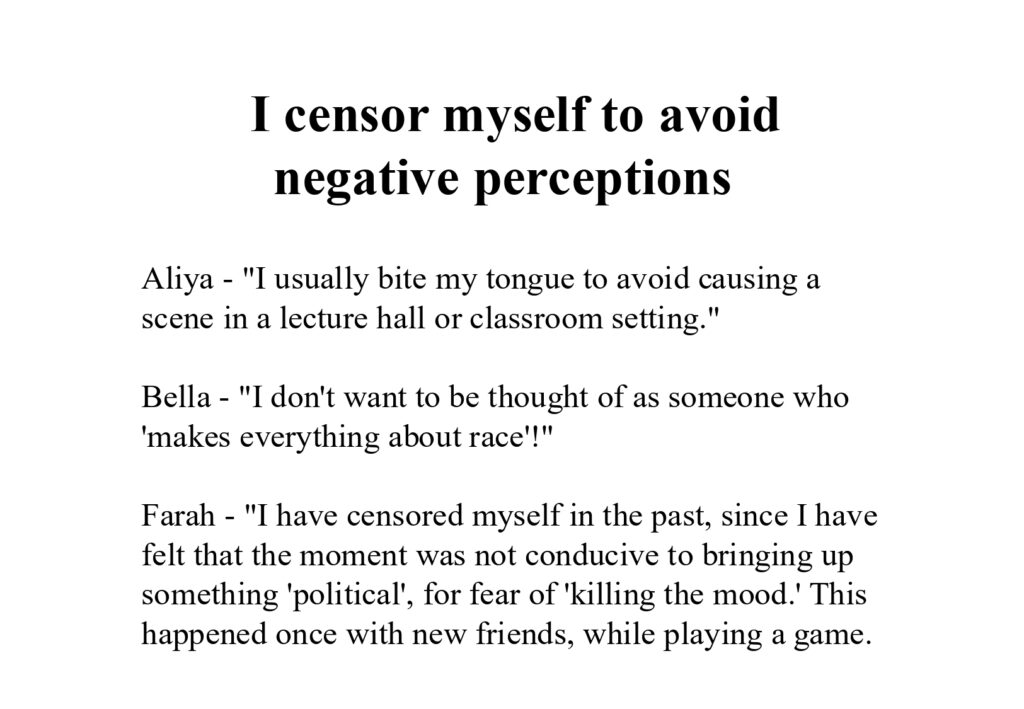

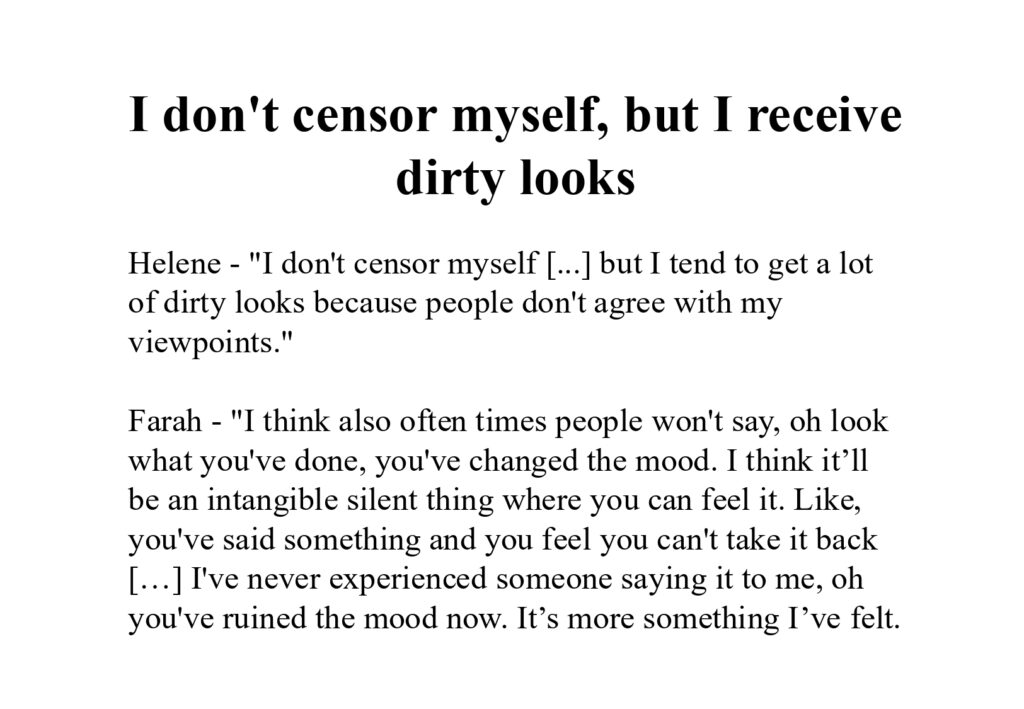

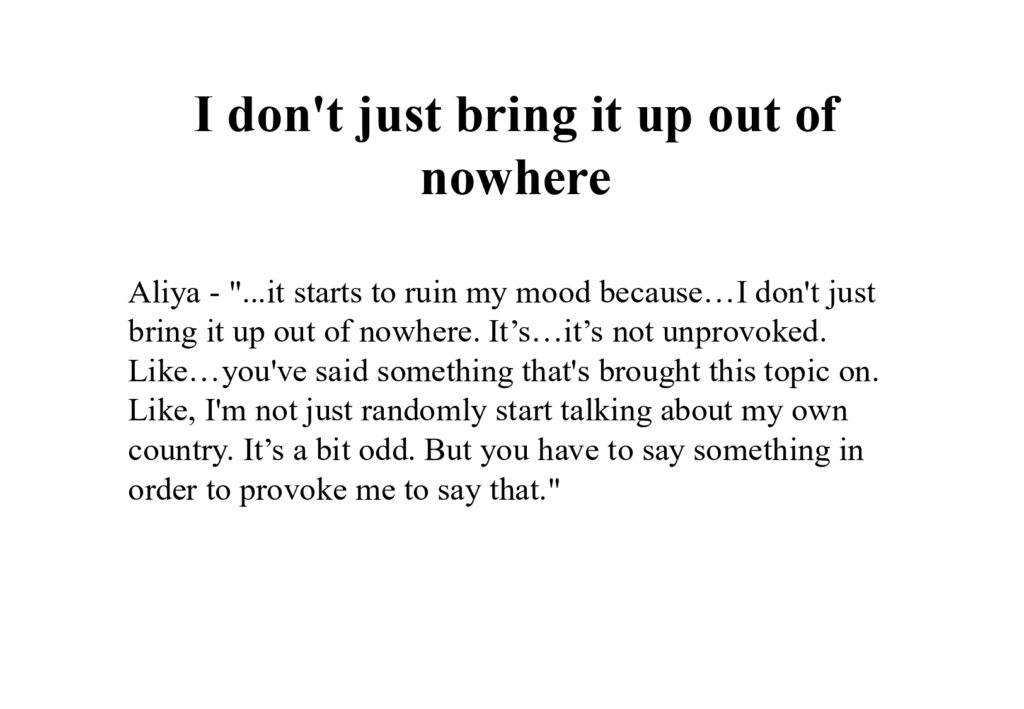

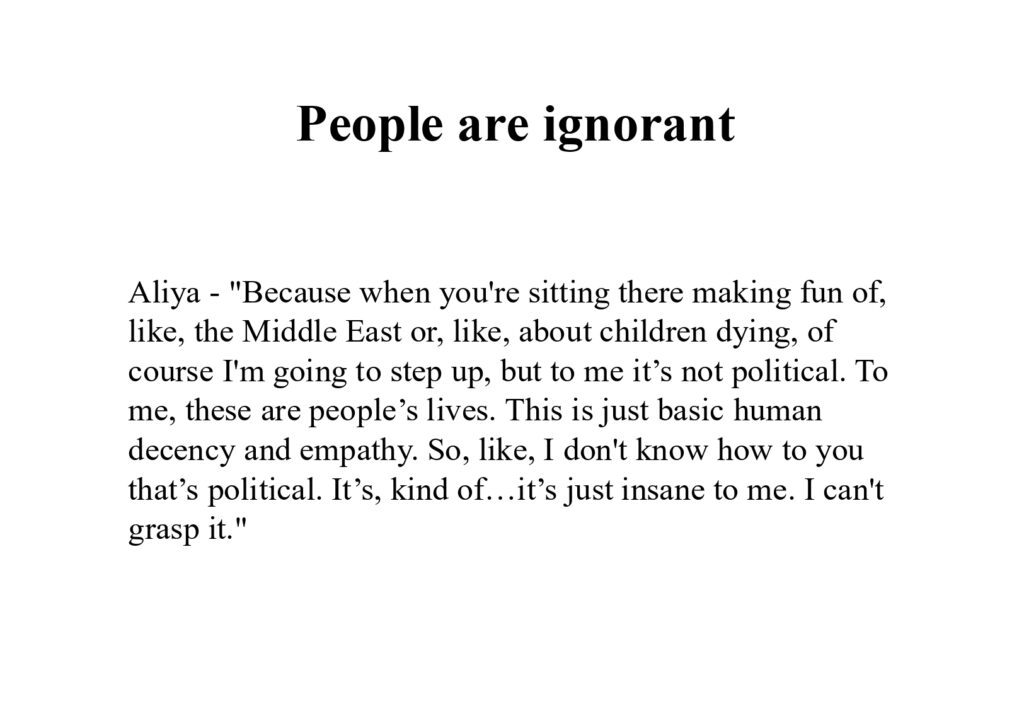

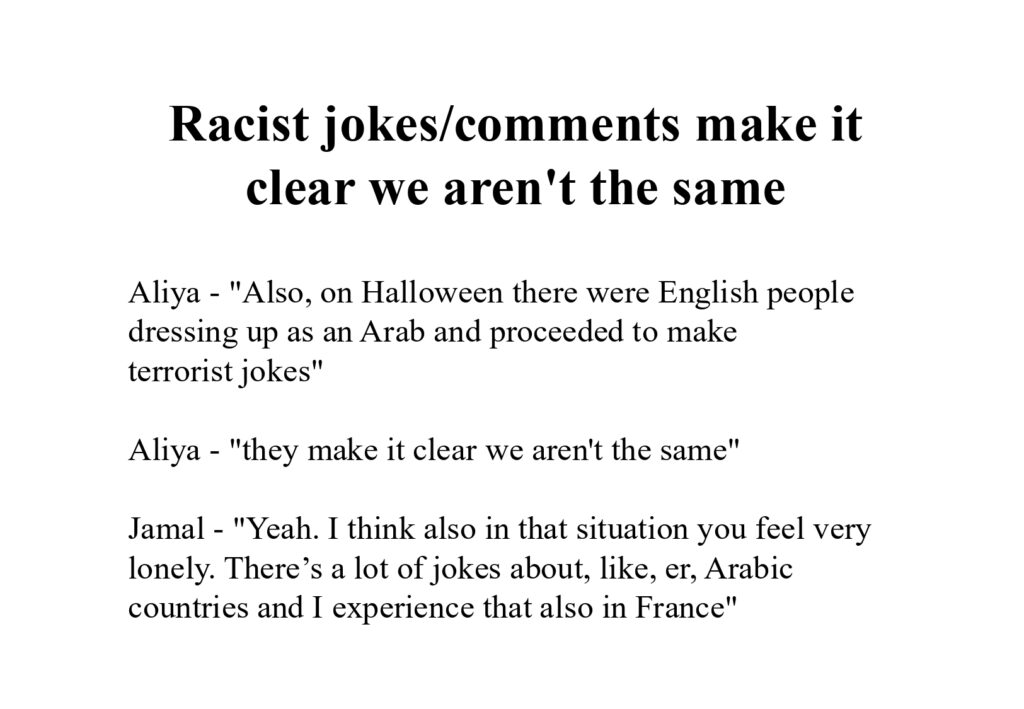

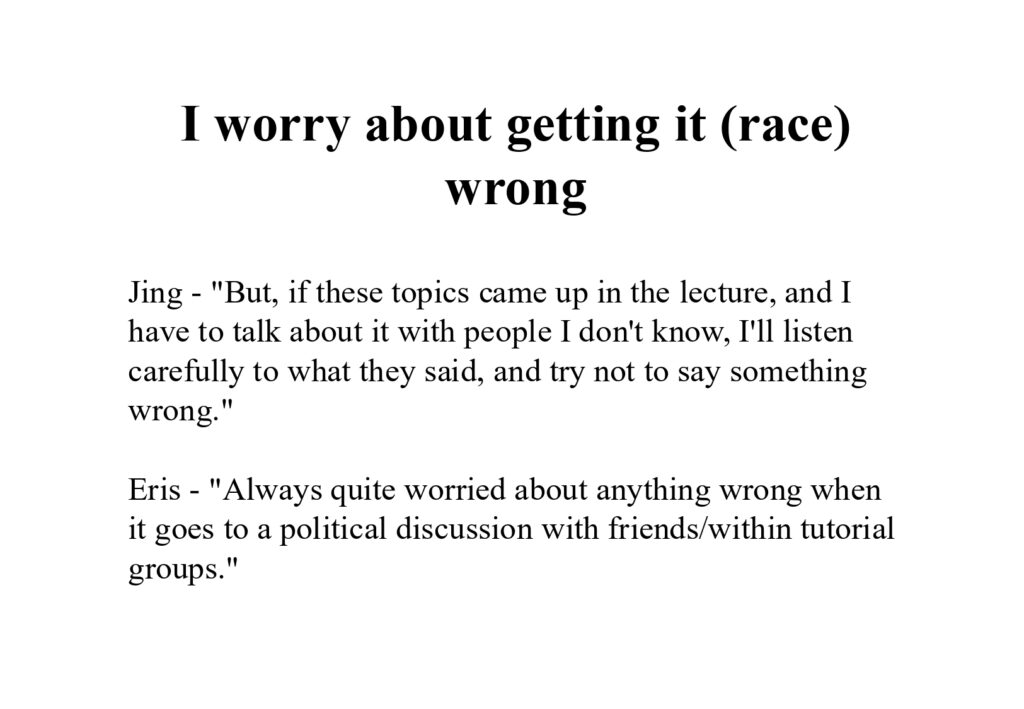

In analysing responses to the question “Have you ever found yourself censoring yourself, when the topic of race or injustice comes up worrying about ‘getting it wrong’ or perhaps being too political?” we noticed the following themes:

Limit Situation:

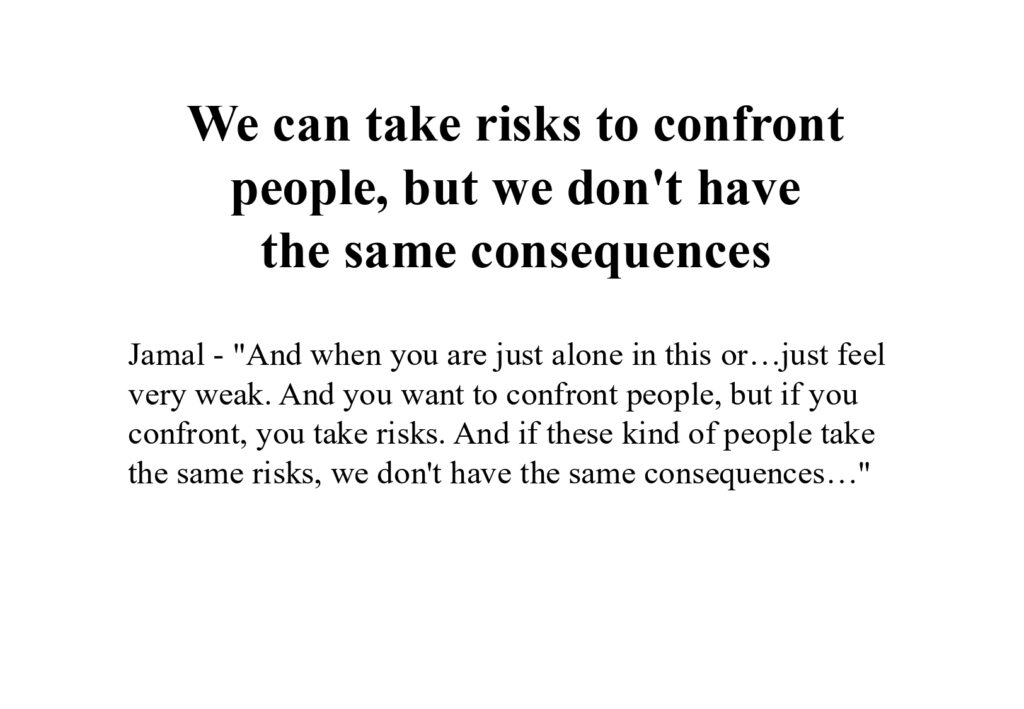

As we co-analysed the above themes with the participants, we (as facilitators) noticed the following limit situations:

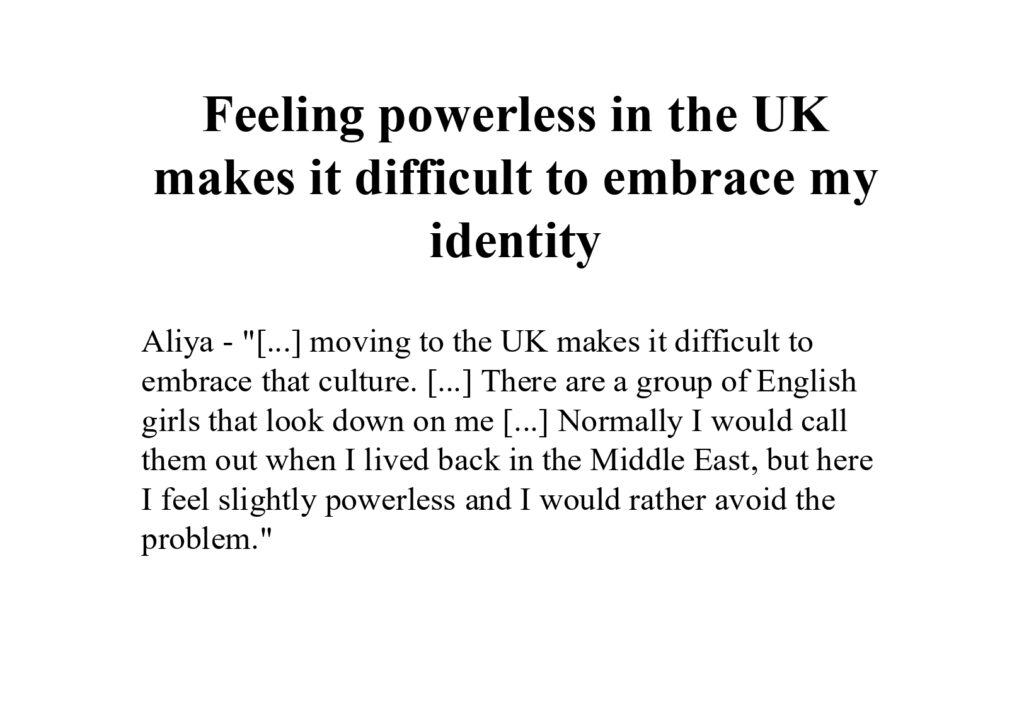

- Feeling like confronting the situation but censoring oneself to not receive dirty looks, to not be seen as a problem, to not receive bad consequences. Thus, feeling powerless.

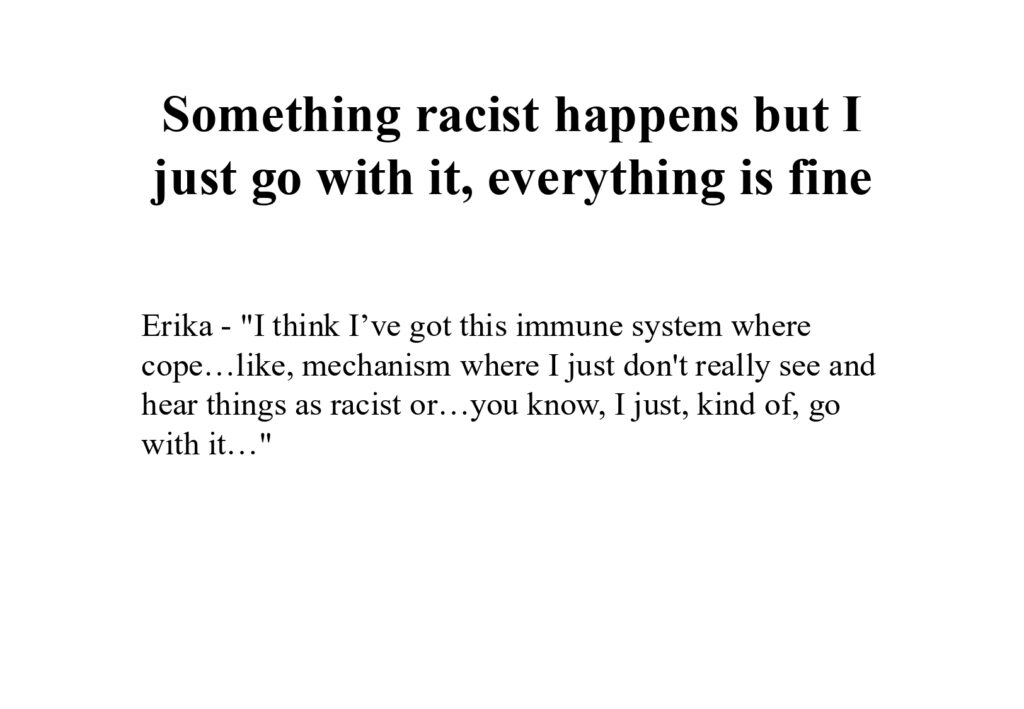

- Having a sense that something is not quite right but it is hard to identify and address. I just brush it off, I just go with it.

Generative Theme: How do I decide when to adapt and when to speak up? What are the risks and costs?

Summary:

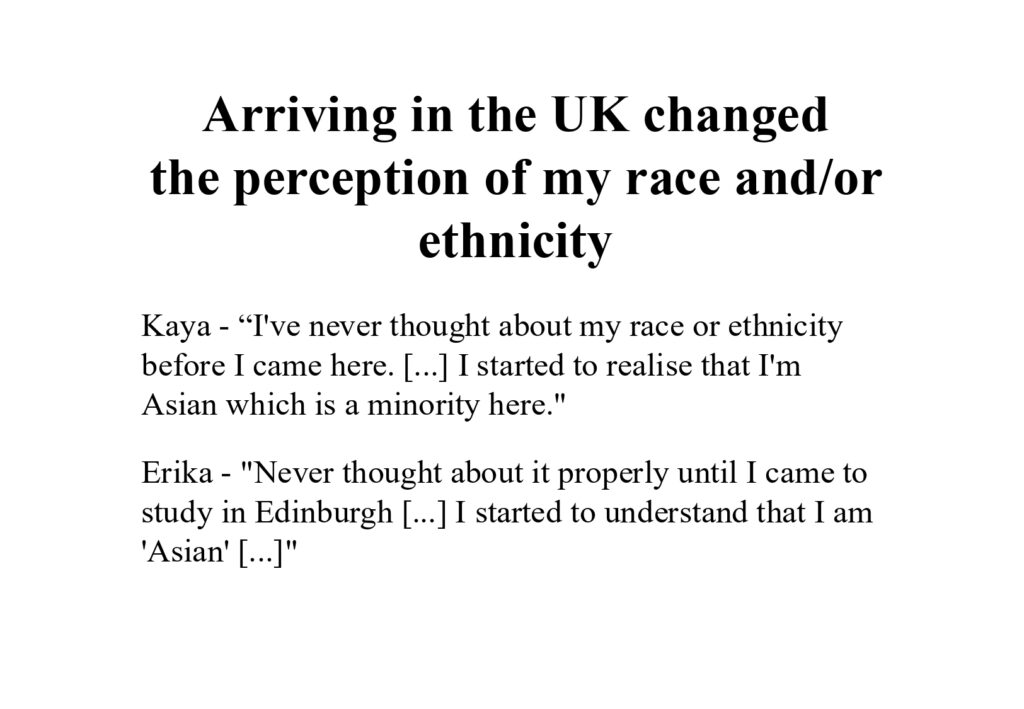

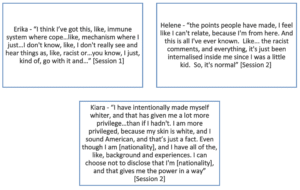

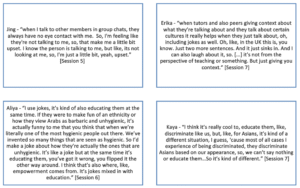

Students spoke about their current responses to racism – how they sometimes brushed it aside, how they often felt pressure to be the ‘perfect’ victim, needing to respond to racism calmly and without anger to not be further stereotyped, or how some of them leaned into being White passing to experience some semblance of power.

As they spoke in the group, they began to express themselves increasingly, even expressing differing opinions, thereby showing a movement away from censoring oneself or brushing aside their experiences to instead claim space and ask or complain. They noted ways of standing up to racism – such as using jokes to educate others and to turn racist jokes back onto those who make such uninformed or stereotyped comments. Even as they began to explore possibilities of action, we were left with the question of ‘responsibility’ and who carries it in interpersonal experiences as students sometimes rushed to save those who questioned their own privilege.

Reflections:

Reflections on Jing, Aliya and Kiara’s process elucidating the generative theme:

For context Jing, Aliya, and Kiara are international students. Jing defined her ethnicity as East Asian; Aliya defined it as Arab; and Kiara defined it as Latin American.

While Jing did not speak much through the sessions, when she did speak, she spoke with a force that perhaps contained a lot of her anger or perhaps it had to do it what she said about not wanting to enhance stereotypes about East Asians and therefore speaking loudly. While she noted not receiving eye contact while speaking right at the outset in Session 1, it made an impact on us only when she restated it in Session 5. Her comment made us reflect on how we implicitly reinforce such biases through our own body language – whom do we make eye contact with? Who gets ignored? The fact that we did not really ‘hear’ her in Session 1 and that her words left a lasting impression only in Session 5 also offers some food for thought – how many times and how loudly does she need to speak to be heard? What are we reinforcing by not hearing it the first time? It seems natural she would speak loudly then and with a lot of force – because being heard by others seems to require such effort. Her process definitely gave us a lot to reflect on.

Aliya seemed conflicted in her positionality – flitting between feeling immense pride in her cultural background and fearing being stereotyped as ‘aggressive’ and thereby having to be the ‘perfect victim.’ She seemed to feel that playing into the ‘perfect victim’ image gave her a sense of empowerment, yet she also voiced the fear behind it which brought to light her conflicted feelings. Given her cultural background and the ongoing geo-politics around it, Aliya’s internal conflict seems to reflect the larger response to genocidal devastation in the Arab world – of wanting to fight back but also fearing the loss of aid.

Kiara came in with a strong sense of her internal conflict, naming the need to be ‘white enough’ or ‘exotic enough’ to fit in and be accepted. She too, however, expressed her dissonance with white passing, how she also used it and leaned on it because it gives her more opportunities and she can decide whether to disclose or not her nationality/ethnicity. In dialogue with Aliya and Karen she got to question whether it is really easier to pass as white given that she knows her nationality and she needs to push down a part of herself. This added another layer to her inner conflict. In the discussions, she consistently named her inner conflict and pointed out the impact of power structures on why she has such internal conflicts.

The above thread of inner conflict in Aliya, Kiara or in us in response to Jing is important to stay with as perhaps exploring this in the group with the Co-Is may have generated further movements and threads of experience. Perhaps, the group was also wary of not having difficult discussions in the ending session. When one of the facilitators, Candela, spoke about her Spanish heritage and reflected aloud on how she was unsure about relating to a country that had colonised parts of the world, students quickly reassured her that she could still proud of her culture, as she did not do it. We wondered if the loss of one White person in the second session (who left after a particularly challenging discussion as other participants recounted how they felt in relation to being asked ‘where are you from?’) could have had a ripple effect of being ‘nice’ to Candela in the last session, and to diffuse any tension. While we can only speculate about what happened (since we did not have the chance to bring it back to the group), we want to highlight the possibilities of what we could have done in the group. The previous generative themes all showed the working through of internal conflicts (that reflect and stem from external conflicts) in some form or another and we wonder what could have happened had we had the chance to bring all this back into the group to work through and grapple with collectively. This also shows the need for sustained engagement rather than one off groups, where students would barely skim the surface of their experiences and personal-social-collective processes.