What do I do when I am made to feel different?

In analysing the transcript from Session 1, we noted prominent themes from the discussion that co-investigators had, specifically in response (including their written responses) to the question “Have you felt different while studying at the University?”

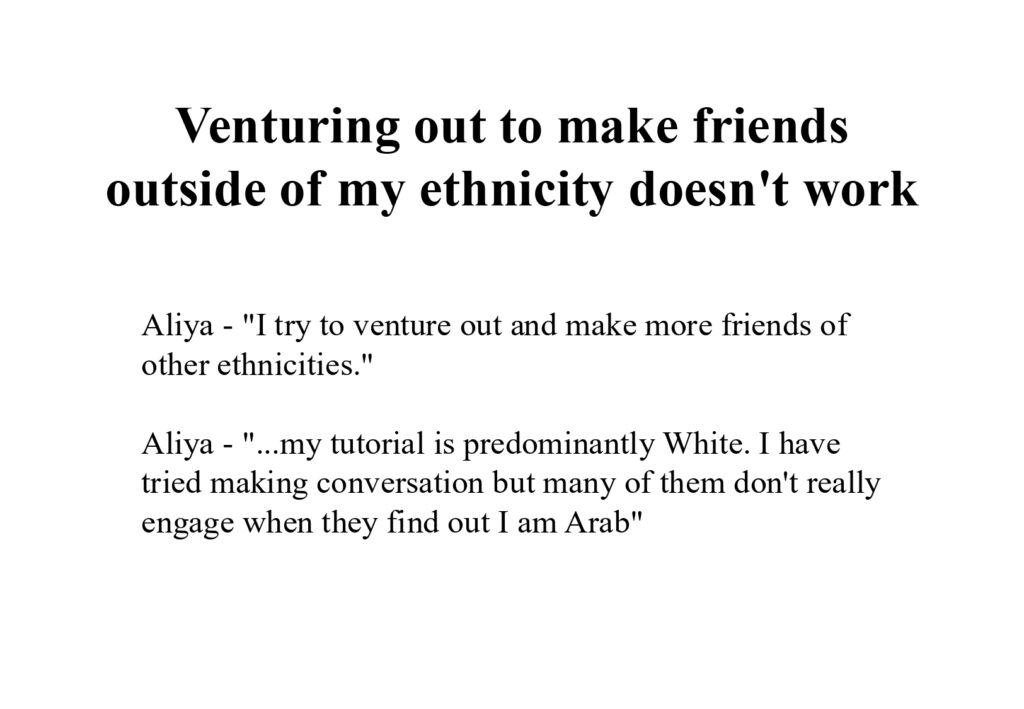

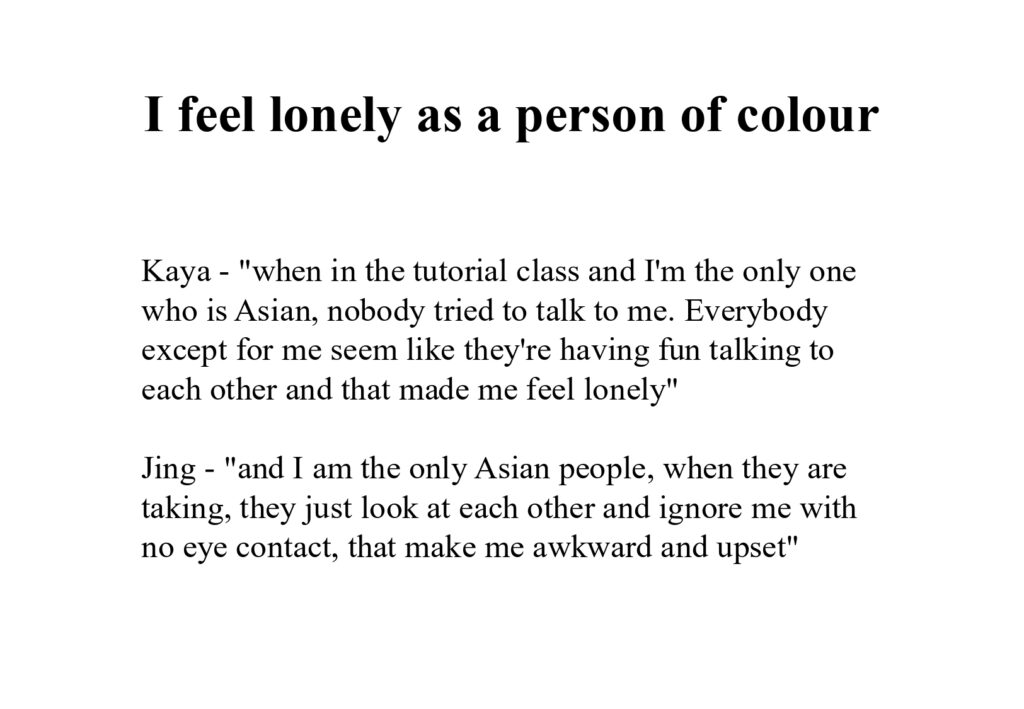

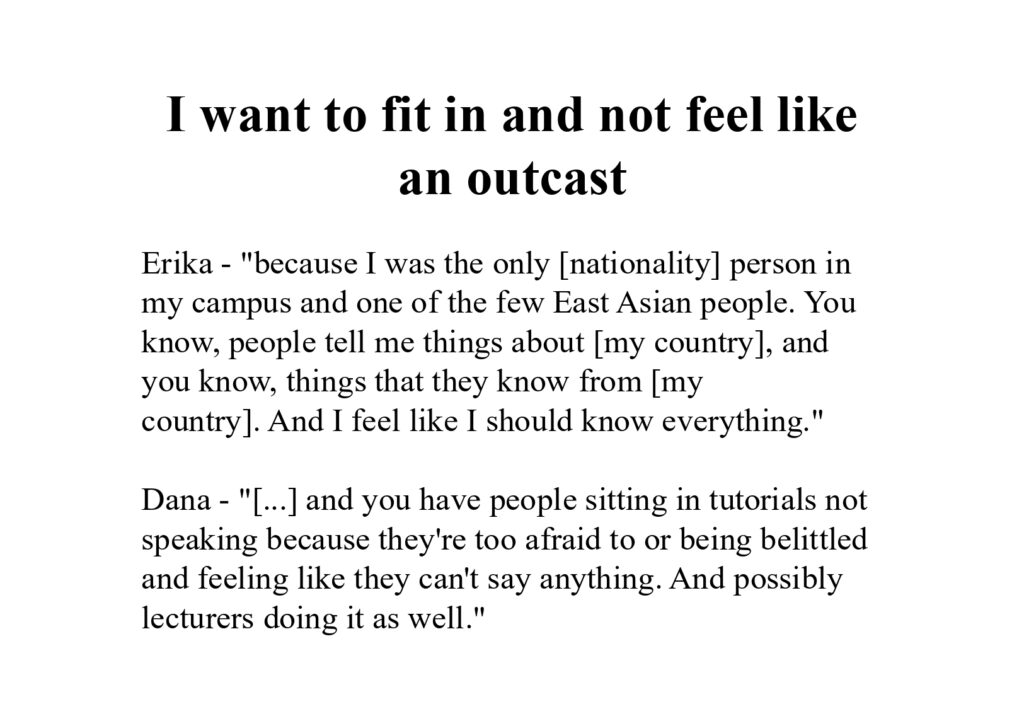

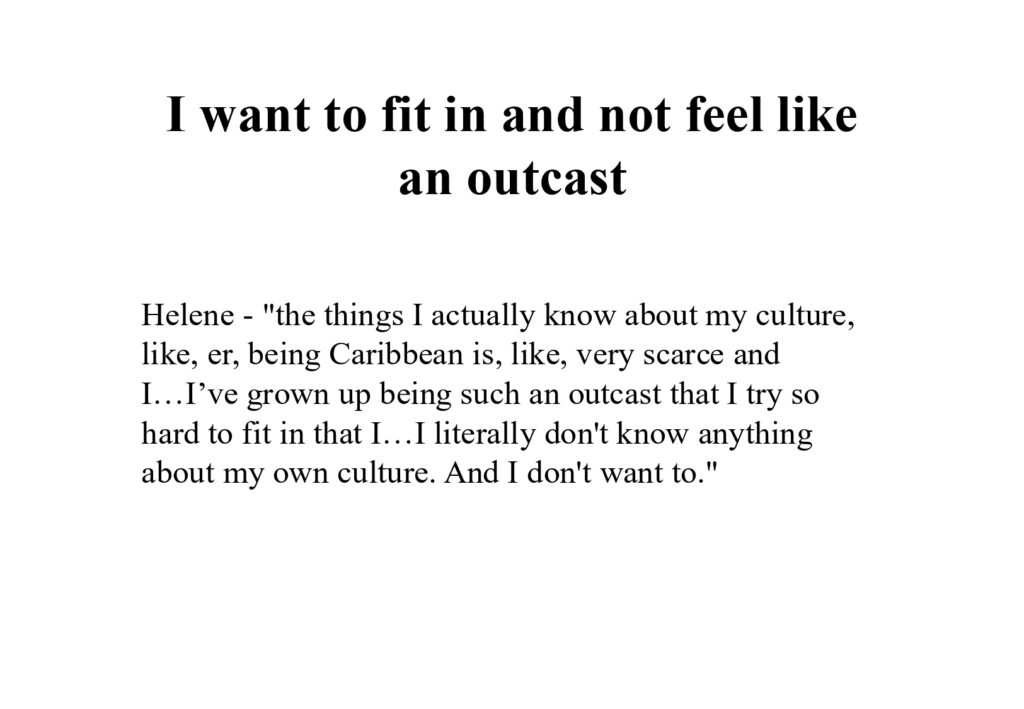

In our Reflexive Thematic Analysis, we identified several themes that stayed close to students’ own words or ways of expressing. We took them back to the group in Session 2 for further discussion, offering the space for students to expand on, clarify, or change the themes that we had identified. Below, we offer 1-2 examples from the transcript for each theme:

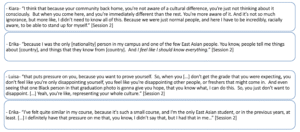

Limit Situation:

From the above, we noticed the emergence of the limit situation:

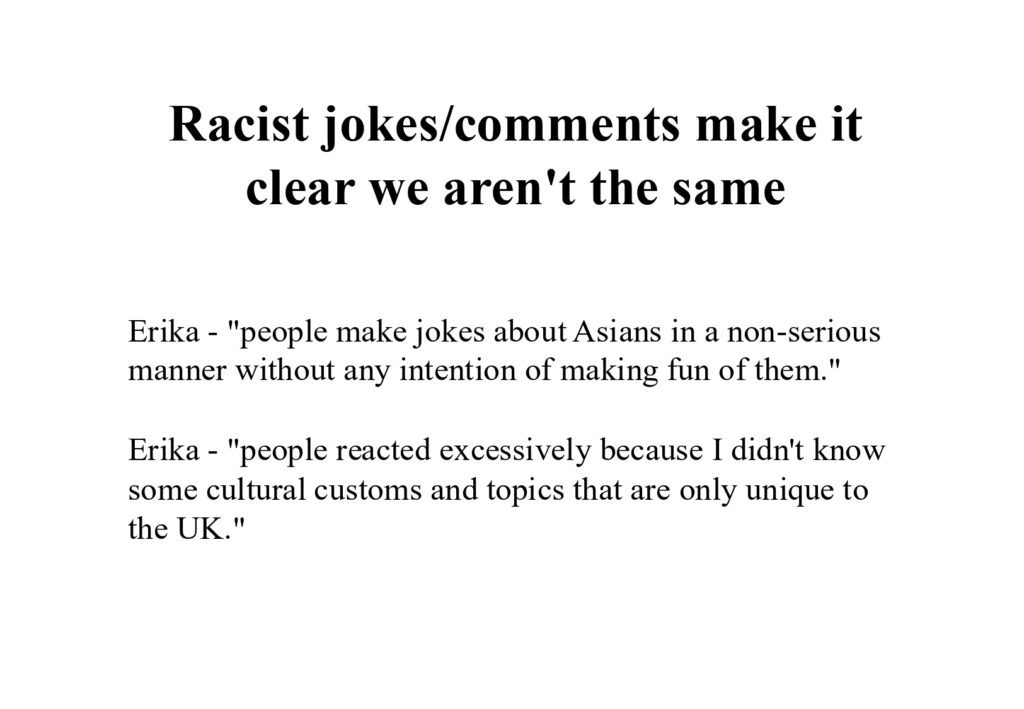

Trying to adapt, to be taken into account, to venture out and make new friends, but finding in response a lack of interest, not being looked at, racist jokes and/or stereotyping.

Generative Theme: What do I do when I am made to feel different?

Summary:

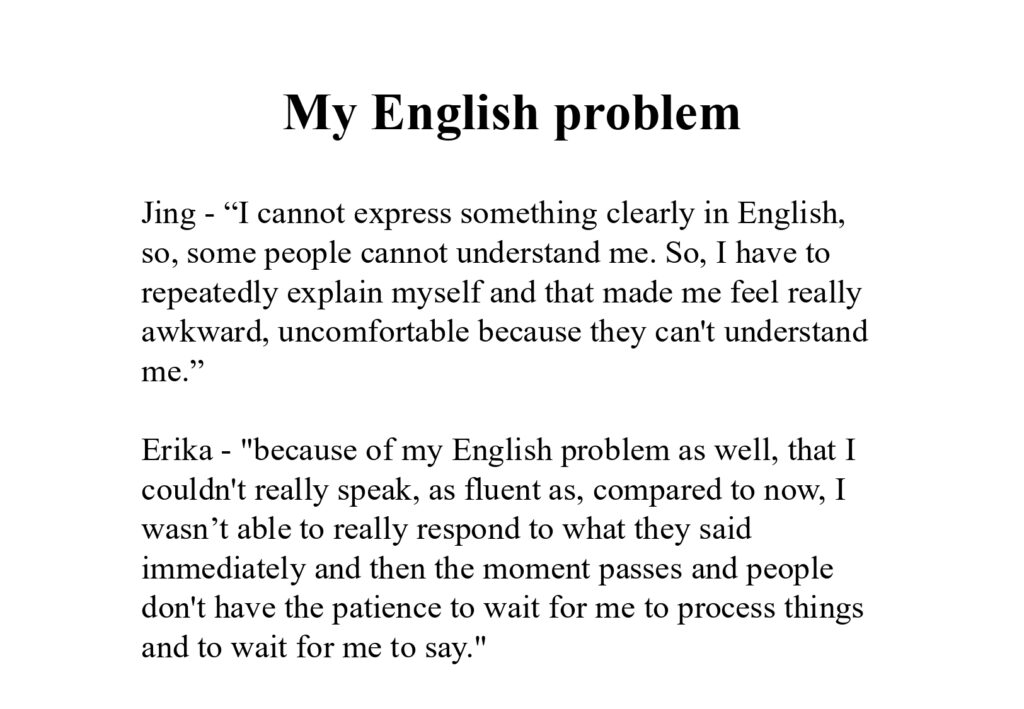

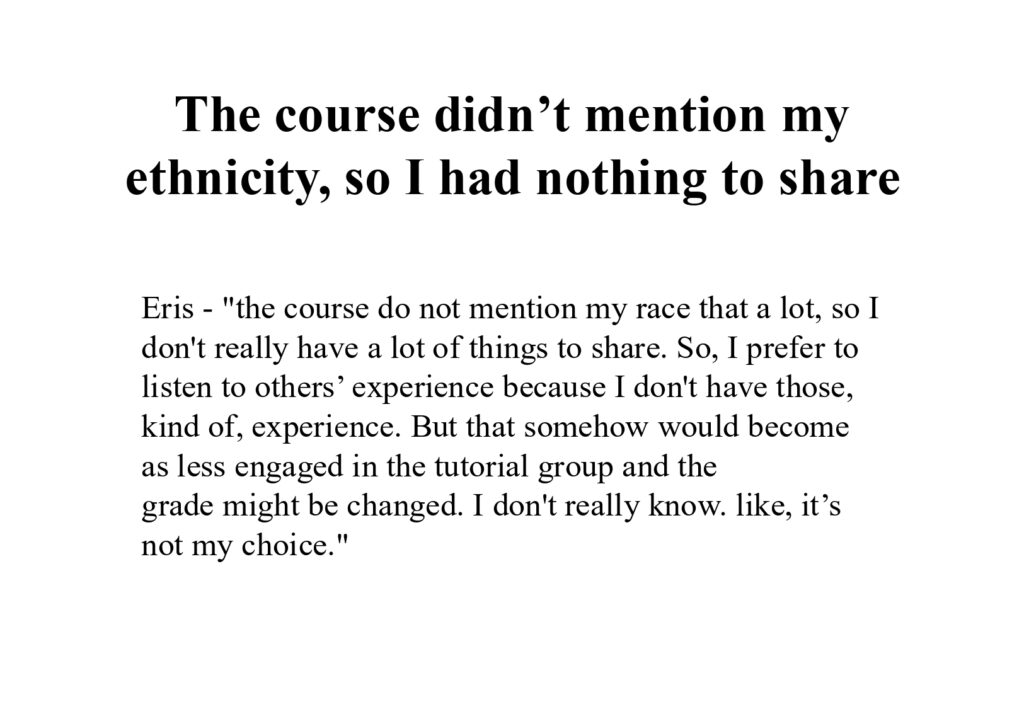

In response to feeling rejected (limiting situation), the co-investigators were internalising a sense of being inadequate or not being enough, needing to try harder. In the initial sessions, co-investigators began by describing their feelings of inferiority and insecurity about a few things, especially in relation to their English language proficiency, and the perception of their ethnicity/culture/country, because fellow students and staff would speak about it in stereotypical ways or plainly not mention it. From this experience, they unpacked that it felt as if they needed to know everything about their culture and represent it perfectly so that others would not stereotype them or ignore them. Having the space to dialogue with one another offered co-investigators the chance to reflect on their own personal experiences with the limiting situation and arrive at pushing the edges of the situation collectively.

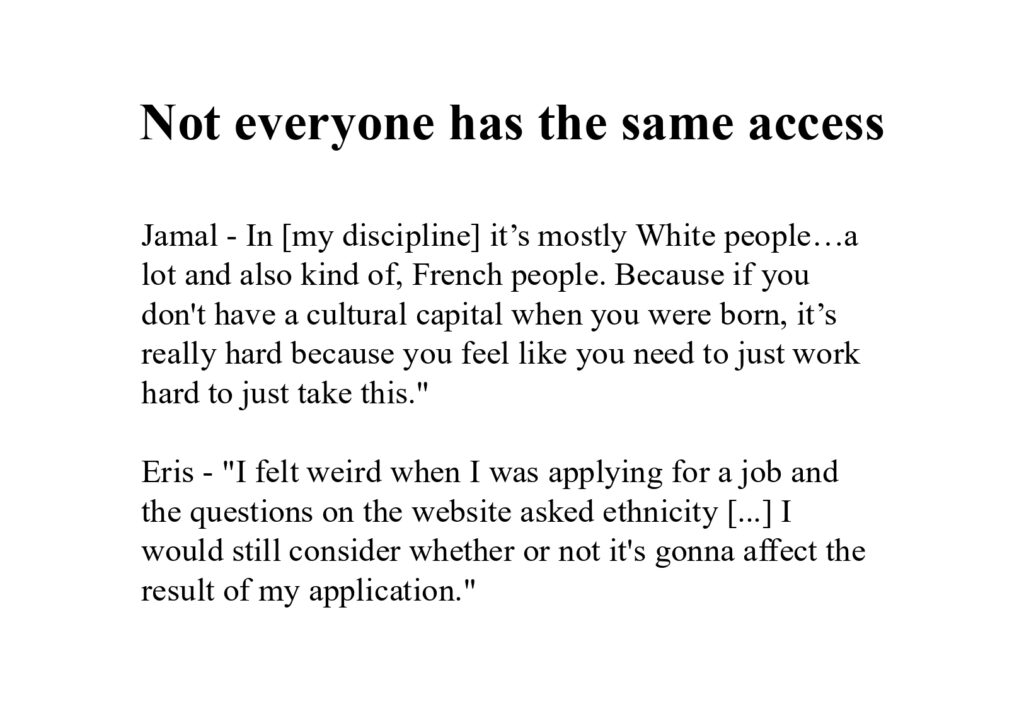

They further questioned this experience in the light of social and interpersonal racist dynamics: that is, they recognised that the weight did not need to be placed on the individual alone, and instead they began to understand this pressure and feeling of inferiority in terms of the self as entangled in an unjust society.

We noticed that this exercise of unpacking and listening to themselves and examining the impact of power structures perhaps allowed them to trust their embodied sense of the situations and to bring it up as a form of knowing.

Their process with this generative theme could be synthesised in this way: when I am made to feel different, instead of internalising a sense of inadequacy and feeling that I need to try harder, I realise that my sense of feeling different has to do with wider unjust social dynamics. I realise that my feelings and sense of the situation are important and I listen to them and also express them.

It is important to note that this might be a movement that we witnessed in the culture circles, but it is not a complete shift, rather a movement to a different way of relating to their sense of being othered that students might be able to enact sometimes.

Reflections:

Reflections on Erika, Kaya and Eris’ process elucidating the generative theme:

For context, Erika, Kaya and Eris are international students from East Asia.

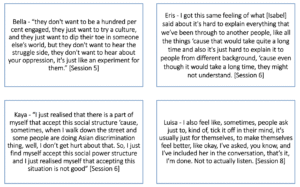

All three Co-Is moved through the generative theme of beginning from a place of internalisation of ignorance, inferiority, and insecurity to becoming more defiant in their expressions of what they experience, recognising the impact of others on them and naming social systems and structural injustices. They also spoke up more in expressing what they needed, thereby having to surmount feelings of ignorance, of not being ‘good enough’, to even speak up and claim space.

Kaya moved from a position of internalising blame, that is, she seemed to note that she was at fault for not getting along with White people as she seemed to stick to her ‘secure’ place of being with East Asians. However, as the sessions moved, she noted ways in which East Asians face discrimination and also expressed her disappointment at White students and tutors not wanting to know about her country’s culture – she noted how she would prefer to be asked about her culture. This shows a possible shift from internalising blame to recognising that she was not being received wholly and therefore, it is not simply a matter of her being at fault. She also noted how social structures are so present in her experience as a student here, thus showing how she was reflecting beyond an internalisation of the blame.

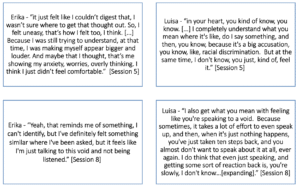

Erika seemed to have internalised a sense of ignorance in two ways: a) not knowing enough about her culture and b) not knowing enough about political and social structures to recognise and challenge racial discrimination. Through the sessions, she seemed to move back and forth between the above internalisation and reflecting on her experiences of a) being expected to know everything about her culture, and b) people not really wanting to know even if they asked about her culture. Most importantly, she began to tap into her felt sense by naming moments of discomfort and unease and to let that guide her experience. It is unclear if she noticed that even though she doubted her ‘knowledge’ of historical/structural influence, her body knew of the impact. Yet, since she began to express her felt experiences, it denotes some trust (at least in the context of this group) in listening to and voicing out her intuitive and embodied responses to racial encounters.

Eris moved from noting that her culture is not present in course content to noting that people actually do not want to know anything about her culture. Even if they ask, they are not often listening, and she does not get any response in return. She further reflected on how dangerous the environment feels to stand up to racist encounters, thereby showing that she was engaging with socio-political structures. She did not seem to start from an internalisation of blame in the initial sessions. However, her engagement with the socio-politics of racism seemed to gain several layers through the dialogue. She reflected on stereotypes, reflected on how the environment contributes to whether/how one responds, and reflected on not feeling listened to and received when she speaks.

Questioning internalised racism, while a challenging task, seems to have begun to happen through dialogue and relationality, that is, from being heard, validated and understood. There were several affective moments where co-Is described a ‘sense’ of something, often unable to put their uneasiness (for example) into words. But being received by others allowed them to move past doubting their descriptions and to instead start trusting their embodied responses to the world around them. Thus, the limit situations of feeling ignorant, internalising blame, feeling underrepresented (or unrepresented) in course curriculum and feeling inadequate with their English were unpacked throughout this generative theme as participants not only noticed and named the impact of social realities on their individual experiences (thereby gaining more of a sense of the whole picture). This further pushed them towards limit-acts – which perhaps in this generative theme feels more subtle, with their slowly growing readiness to listen to, validate and speak from their embodied responses to injustice.