Students’ names:

Students noted feeling seen when tutors choose to call them by their Chinese names rather than their English name. They noted that they choose an English name so that it is easier for others to pronounce their name but would rather appreciate it if someone put in the effort to call them by their actual name – to meet them halfway:

“I use my Chinese name when I’m back home. And when I came here, I think <English name> is easier for foreigners to pronounce.”

“The thing that I remember that happened in first year is I use my Chinese name… when they do the registrations they have to spell out and speak about my Chinese name. And it’s hard to pronounce for a foreigner. But when I told my tutors to call me <English name>, she’s just saying no, I have to speak out the name you prefer. I think it’s really caring.”

In addition, the discomfort with tutors mixing up names of students within the cohort was also pointed out:

“Tutors I would say are really bad with names. Even on my course, it’s very small, there’s twenty of us, and they get every student of colour mixed up, even if they don’t look alike.”

Course content:

Students spoke about course curriculum and the need for more diverse content from across cultural backgrounds. Students shared appreciation for feeling represented in their course curriculum:

“My course is good because we have a week for everything. We have one week is sexism, the next week is racism, the next week’s ageism. We cover everything every semester, so. […] I feel really represented in my class.”

And for being encouraged to speak more about their cultural experiences:

“I have lots of tutorials with my tutor… and in the past two years especially I’ve been encouraged to bring up any artists or any research that I’ve found from Japan. I see that as <school> improving at least in my course. Because four years ago I remember all the students complaining about that. But now I hear some tutors talking about it. And that’s been great for both sides because they want to know all those artists and research and I get to introduce them.”

Though this was not the experience across the group:

“I would say mainly that my tutors have been great. I feel like a lot of examples they’ve taken a lot from the Scottish culture, which is really important because we are here, and I get that. But it’s either just Scottish or UK, and nothing else. So, I think sources of information is important. Especially when it’s historical examples of things it’s really Eurocentric. So, more varied sources would be good.”

Students recommended having more variety in course curriculum to know about diverse contributions to the field from across cultural contexts would be helpful:

“Highlighting, like, a particular culture’s history and its ties to the subject for example. Or, like, um, appreciating the contribution that people of colour have made to the discipline. If there was, like, a lecture for say, like, on, um, like, historical contributions, um, that could be interesting.”

While students called for more diverse examples and case studies to be included in the curriculum, some other students also pointed out the need to be careful not to stereotype cultures:

“I think for my ethnicity, it’s not that we don’t get brought up, but we get brought up in a bad light. They word it in a way that’s either war or a conflict, or somehow, they put it on us.”

“Arabs are always brought up in war context. It’s never about the inventions we’ve made, the contributions we’ve made to society, it’s always in a bad light. So, if they’re going to keep bringing it up that way, they might as well just not bring it up at all, because it’s tarnishing our reputation… you’re just adding onto the bad name for Arabs and North Africans…”

“Many professors and students like to use the Middle East as an example for conflict and effects on economy in business classes. Many blame the Middle East for war and terrorism, they come off as racist and uneducated.”

What constitutes engagement in tutorials?

Students were seen as less engaged in their courses because they did not contribute to a discussion that was not relevant to their lived experiences:

“[in] the tutorial group […] because […] the course do not mention my race, so I don’t really have a lot of things to share. So I prefer to listen to others’ experience because I don’t have those experience. But, that somehow would become as less engaged in the tutorial group…and the grade somehow might be changed. I don’t really know… it’s not my choice.”

“especially in the beginning of my uni life, you know, all I could share was things that I knew […] I wasn’t sure how much I could share about this East Asian background, like cultural information […] Because people just didn’t seem to get interested, or they didn’t really respond…maybe they didn’t know how to comment on what I was sharing at that time. […] But at that time, I, in a way, censored myself for not sharing too much, because I thought, I’m making things boring.”

Especially if the course content is not directly relevant to their culture, students find it hard to catch up and relate to the examples offered:

“when tutors and peers give [cultural] context about what they’re talking about […] it really helps…Just two more sentences. And it just sinks in. And I can also laugh about it [if it is a joke], so. […] it’s not from the perspective of teaching or something. But just, just giving you context.”

Further, students spoke about their internal struggles in relation to speaking in a language that is not their first language and fearing being judged or stereotyped:

“I feel I’m scared, I was always thinking, I’m scared to enhance a stereotype of how Chinese people would be, if they’re not good at talking English. So, I’ll just keep in my mind, and like, stopping me from thinking about what truly matters in that course.”

“sometimes I found it’s hard to say if this is the most polite way to say other’s name, or call a lecturer, or to talk, like a tutor. Like, what is the most polite way to talk to them. And I worry about whether this is going to affect other conversation or not. And also, this is something stopped me to ask questions last semester…”

Based on the above experiences, students offered suggestions and ideas that would be helpful for them in lectures and tutorials:

- Tutors must get foreign students’ names right.

- Tutors could encourage students to share more about their own cultures.

- More diverse sources, literature, examples or case studies could be included while being careful not to stereotype.

- Course organisers could share strategies or materials amongst each other that are diverse and have been impactful with their own cohort of students.

- Tutors could be mindful of having students from different cultural background: by giving more context to their examples, content, and ideas that are from British culture, by recognising that students may not be speaking up because the content may not be relevant to their own life experiences, and by respecting the space and time it takes for students who are learning in their second language – giving enough time for them to respond, not interrupting them as they speak, and not speaking for them, instead letting them express themselves.

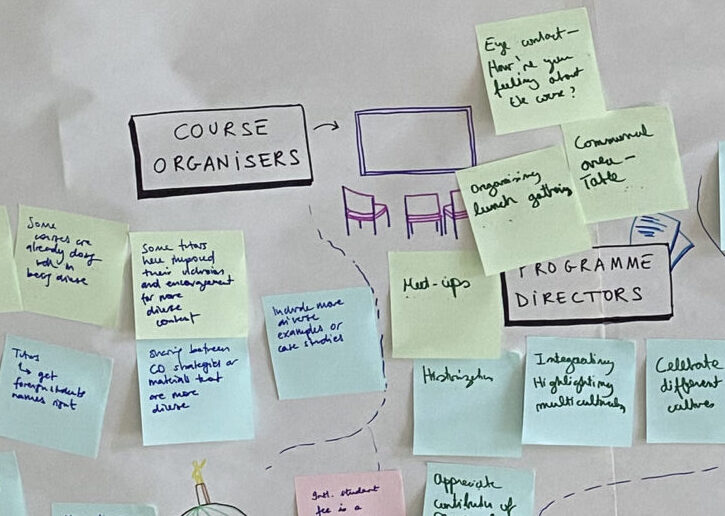

Students, however, also appreciated some of the ways in which programme directors and course organisers created communal spaces and made them feel welcome:

“My programme director this year has been amazing in my opinion. It’s such a small group but she’s organised, like, lunch gatherings, which was really informal but she, kind of, brought everyone together and, um, it just created this nice I think informal setting of conversations.”

“We just chatted to each other. And she was very active in asking people, making eye contact, like, how are you feeling about the course, like, how is your experience now, um. And it just made, like, a very accepting, like, community.”

“she does these, like, meet-ups every fortnight or something in term time where there’ll be, like, a guest speaker and there’ll be food and we can just chat.”