I was blown away by the Angelica Mesiti exhibition In The Round, at Edinburgh’s Talbot Rice Gallery. Installations Over the Air and Underground (2020), and Citizens Band (2012) went straight home for me. At the invitation of ESRC postdoc, Laura Harris, and curator, James Clegg, I wrote this creative response to the exhibition for their event, In Another Tongue.

[The opening passage picks up from the occasion and imagery that I wrote about some months ago in this blog post, but takes a different turn. I have elsewhere written and published more scholarly texts on some of the ideas described here – like this, and this.]

Sound-making is movement

I’m alone but I’m not lonely. I can hear the piano tuner’s progress, his temporal journey from low to high. Without thought, I’m in step with his decisions, which are evident in the vibrations and resonance that say, “Work done. This one is ready now, time to move on.”

What a luxury. What a privilege. I have safety, I have warmth, I have refuge. I have a piano – not a travelling instrument, it is furniture. And my piano has eighty-eight keys, eighty-eight notes. Their boundaries are clear and ordered, pre-determined by consensus. I have the privilege of company, in my solitude: the piano tuner and I observe, together, the discipline of equal temperament.

*

Our human experience with music is one of interfacing: I interface with music as it comes to me in sound and movement. Because sound-making is movement – it comes from vibration, from events of action; from airborne pressure changes that permeate our bodies’ physical margins.

Over the air, musical sounds sit in imaginative relief, distinguished from background noise by our recognition in them of patterns and signals.

We can theorize about the patterns. We can evoke them abstractly, inscribe them symbolically, explore them discursively. These patterns afford us the imagination of conceptual structures, rules, and conventions. Of theory. The degree to which (and manner in which) diverse musical cultures use theory varies, ranging from informal, implicit learning — technical attention given to complete items of performative repertoire — to explicit and complex symbolic literacy that fosters theoretical as much as embodied generation of new material.

But to make music is to participate in humanity; to communicate the realization of our expressive vitality.

Expert musicians have mastery in the production and modulation of sound. Their intentional control of an instrument of any sort (including the voice) requires fine motor control, expert co-ordination of independent movements between limbs or parts, and the assimilation of feedback between aural and motor processes at a very high temporal resolution. Music is an integrated expression of body and mind.

So, musical performance comes in skillful, multi-modal and temporally integrated technical proficiencies: actions that deliver the pressure changes that bring us patterns in sound and behaviour. Our encounters with music, then, as sound in air — as auditory experience — already encode action, bodies, movement. Distinguished from background noise, these are the patterned signals whose relief imprints upon bodily imagination.

Inherent in pattern lies order. And in order, we can infer intention, instigation, agency: through our encounter with pattern, we encounter others. Others with bodies like ours, who share the common experiences of breath, and breathing; the same mechanics that motivate and sustain voices, limbs, digits. But: Which others?

In Mesiti we meet strangers and their displaced mastery. Music lifted up, out, away from home. There’s no domestic sanctuary here. No piano furniture. No refuge in the colour-blind pretence of conventions of equal temperament. What becomes clear, is that the rupture presented to us is ours, too, as we witness the partly-familiar musical technologies; as we witness the vulnerability of the performers’ commitment to expression.

*

When it comes to music and its communication: what’s fact, and what’s fiction? What’s in tune? What’s out of tune?

The ‘musical structures’ to which we ever respond, as listeners, they may reduce to an auditory signal. But music arises from our essentially social, human existence — from our embodied interaction with one another and our world.

Over the air, this expression of logic and discipline stands as cultural identity, subject to political legitimacy or stigmatization. Our individual acts of musical performance express values of in-tune-ness, in-time-ness, proficiency, generativity, novelty, beauty.

But: Shared world, common bodies, interior beginnings stacked and grown one inside another.

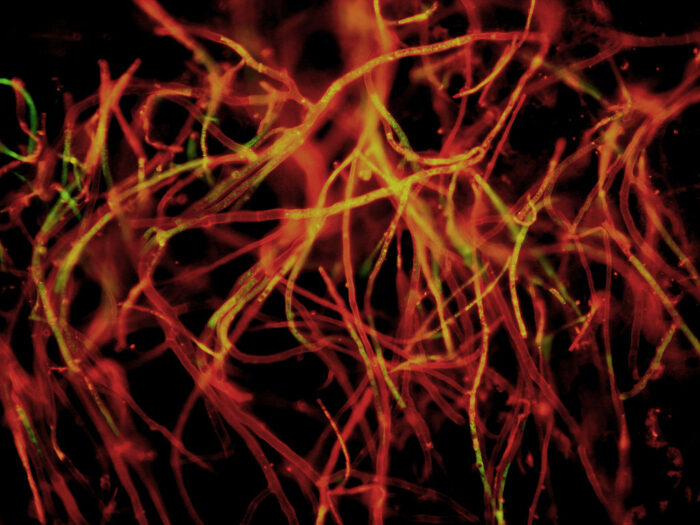

Underground, under skin, music emerges from the connective mycelium of our absolute interdependence. From sympathies of sound in movement.

Image credit: Mycelium. This image shows a group of elongated cells (hyphae) from the filamentous fungus Podospora anserina. They are labeled with a fluorescent stain, JC-1, that labels areas of high metabolic activity (orange-red staining). It was taken by a high-resolution camera attached to a fluorescence microscope. The magnification is 630x.

Christian Scheckhuber, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

(Christian Scheckhuber, CC BY-SA 4.0

Leave a Reply